Preparing for the flood

Architect Adam Yarinsky designs a New York City that faces rising seas

Alexandra Ossola • April 28, 2014

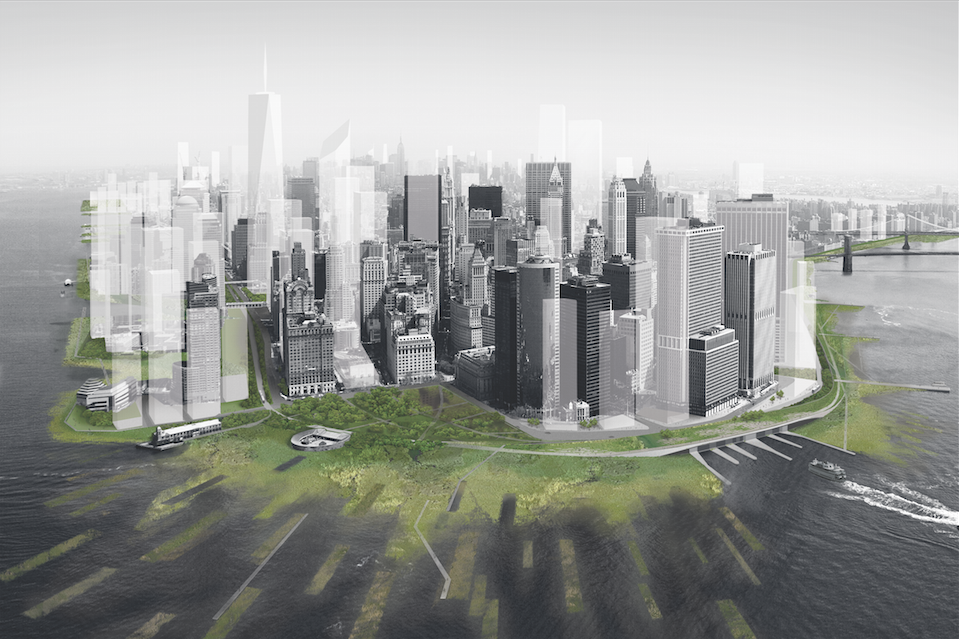

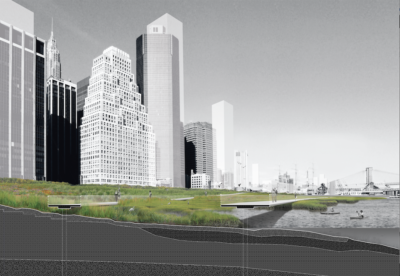

A rendering of New Urban Ground. The plan envisions barrier islands off the shores of Manhattan to guard against storm surges. [Courtesy of Architecture Research Office and dlandstudio]

On a snowy February morning, architect Adam Yarinsky surveyed the skyline from the window of his spacious Manhattan office. He is a modest man of average build, and the soft morning light glinting off his frameless glasses accentuated his Groucho Marx mustache. His gaze swept across the silhouettes of famous buildings, pausing in a relatively bare corner of the landscape. “I love this part. See that hint of green there? You can see right into that closed courtyard,” he said.

This is a theme for Yarinsky: finding the green in unexpected places. As one of the three principals of the accomplished New York design firm ARO (for Architecture Research Office), Yarinsky has spearheaded more than 100 projects over the past 20 years. But the ARO project that has earned Yarinsky the most attention of late has been a conceptual one: a re-imagined New York City crisscrossed by spongy, permeable roads instead of gritty asphalt, and ringed by glistening green estuaries that roll into barrier islands.

Yarinsky’s “New Urban Ground” project exemplifies an overall shift toward a pragmatic, interdisciplinary view of architecture. “I think the notion of design has changed from a narrow, formal standpoint — how something looks — to how something performs,” he said. Along with this shift toward the practical comes a greater preoccupation with the public and its perception of design.

The project was part of a 2010 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art called Rising Currents: Projects for New York’s Waterfront, showcasing proposals to prepare New York Harbor for higher sea levels. The goal, according to the MoMA website, was for design teams to create plans that incorporate “adaptive ‘soft’ infrastructures that are sympathetic to the needs of a sound ecology” and to re-imagine residents’ relationship to public spaces.

Yarinsky’s project, and the MoMA exhibit, are part of a much broader movement to envision how the world’s major cities — most of which are on coasts — can best prepare for the rising seas and fiercer storms that global warming is already bringing. The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projects that seas will rise between 10 and 39 inches by 2100. In New York City, levels are expected to rise even higher, perhaps as much as five feet.

Cities are especially vulnerable to flooding because asphalt and concrete almost cover the ground completely, leaving excess water nowhere to go but the sewers. And the sewers in New York, as in many other large cities, are old and undersized. Since New York’s antiquated system is used for both sewage waste and storm water runoff, it is easily overwhelmed during heavy rains. The raw sewage ends up bypassing treatment plants and going straight into waterways. Yarinsky and many others have suggested replacing asphalt with permeable surfaces like porous asphalt and paving stones that would release runoff into waterways more gradually. These roads would work in conjunction with rows of roadside plants “specially selected for their tolerance for pollution and saltwater,” according to the plan. In addition, man-made marshes would replace the seawalls that currently edge the shores, further soaking up and filtering the wastewater.

The plan also calls for an array of smaller barrier islands off the tip of Manhattan to absorb the pounding waves when storms hurtle towards the city. Engineers could create those islands by pushing sediment through geotextile tubes—the same technology that creates designer islands in places like Dubai. The rendered image, extending like ghostly green arms, is particularly arresting, a horizontal echo of Lower Manhattan’s towering skyscrapers.

New York City has a long way to go to be ready for rising sea level, according to Yarinsky, and many of the tasks the city faces are a lot more prosaic than constructing swamps and islands. Architects need more data to determine how storm surges affect buildings, and government agencies must find creative, cost-efficient ways to protect vulnerable neighborhoods, instead of relying on expensive preemptive changes to building codes or post-disaster aid.

But some climate experts think that strategies to protect low-lying neighborhoods, including elaborate plans like Yarinsky’s, are too focused on the short-term, and could give residents a false sense of security as sea levels keeps rising.

“The MoMA exhibition was a great experience, but the solutions…were totally inadequate,” said Klaus Jacob, a geologist at Columbia University who has published extensively on New York City’s watery future. The best solutions, Jacob said, are those that reduce investment in land that will be too far-gone if oceans rise to the highest predicted levels. “The question is how do we transition from our present situation that reflects the historic past to the future that is inevitable,” he said.

Yarinsky and Jacob agree that all levels of government must be an integral part of this transition, strategizing and implementing creative solutions. They are interested to see how new mayor Bill de Blasio will build on Michael Bloomberg’s layered PlaNYC, which takes a critical eye to infrastructure as New York City becomes more populous. Bloomberg created one element of the plan, the Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency (SIRR) after the destruction caused by Hurricane Sandy in 2012. The following summer, the administration released the SIRR recommendations for disaster preparedness, which range from elevating homes in low-lying areas to protecting electrical and water systems that may soon be inundated. On his website, de Blasio indicates that he plans to implement the SIRR recommendations. But Jacob and others say initiatives like PlaNYC aren’t aggressive enough in moving people and assets out of harm’s way. He puts more credence in the foresight of real estate developers — the “smart money,” as he calls them — who would move to make less vulnerable parts of the city more desirable to residents for financial reasons.

Yarinsky counters that change must come gradually as with SIRR’s incremental recommendations. As more severe weather puts citizens at risk, governments will be under increasing pressure to act. “I think this is a kind of unstoppable tide on a national political level,” Yarinsky said. “We can’t go back to an era of manifest destiny with its individual rules.”

Yarinsky has been dreaming of healthier cities for a long time. Growing up in Albany, New York, he recalls visiting the grandiose Empire State Plaza and ornate New York State Capitol. While these spaces were beautiful, they were unconscionably expensive and displaced thousands of people. His own designs serve more of the public interest, ranging from transformations of university dorms and academic buildings to a renewal of New York City’s iconic Union Square, and reflect a preoccupation with how visitors will use and move through the spaces. “I’m very optimistic — I have two kids and think about the future beyond sort of amorphously trying to do good,” he said.

The greatest opportunities, Yarinsky believes, will be in making buildings work in a network with one another. “A building is not just an isolated element,” Yarinsky said; they are part of a grid and must share limited resources such as water and electricity. There is even a growing movement to incorporate recyclable construction materials — used with the understanding that other buildings could be made from the eventual wreckage. “I think it represents the maturation of American society because we’ve run out of space,” Yarinsky said. And unlike in past epochs, the aim of design projects can no longer be to indulge only a privileged few.

“The idea that quality of life can be in itself the goal is a transformation culturally,” he says. How that transformation will unfold in New York City and beyond is something that not even Adam Yarinsky is bold enough to predict. But he hopes that it might look something like his dazzling green and blue vision of the New Urban Ground.

1 Comment

Good post. I learn something totally new and challenging on sites I stumbleupon everyday.

It’s always interesting to read content from other

writers and use a little something from their sites.