Scientists have injury on the brain

Sample-stretching technique lets researchers study brain injuries using living tissue

Shira Polan • October 4, 2015

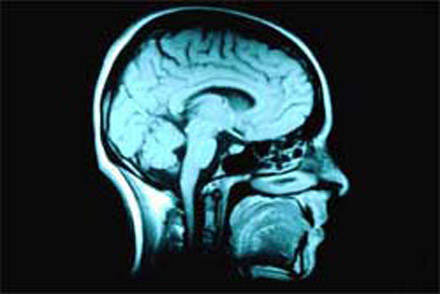

“Your brain is not a beach ball. It does not bounce around inside your skull,” says Barclay Morrison, who instead compares the brain to Jell-O.

A professor of biomedical engineering at Columbia University, Morrison wants to dispel the common misconception that during a car accident, the brain bangs about inside the skull. Instead, like gelatin in a bowl, brain cells warp as their container, the skull, is jostled, he says.

Morrison and his labmates study brain injuries and design equipment to prevent brain damage. Unlike a machine, he says, brain cells can die long before the tissue begins to rip after a crash, which is why traumatic brain injuries, or TBIs, are not always obvious. Falls, car accidents and sport-related injuries are the most common causes of TBI, which accounts for 30 percent of all injury-related deaths in the United States and costs the U.S. $75.6 million per year, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There is no readily available treatment for TBI-related brain damage. “Right now, prevention is the best way to treat TBI,” said Morrison said at a Sept. 17 lecture at Columbia University. However, he believes his research could help neurologists stop the initial damage from getting worse. “We have a two to three day window after initial trauma where we might be able to treat injury before cell death,” he said. “If we can understand how the mechanical blow gets translated into biological damage, we can start developing drugs to halt the process midway.”

In order to accomplish this, Morrison and his team simulate injury-causing events using slices of rat brain tissue that can survive for weeks in the lab. The researchers can recreate car accidents, football tackles and even explosions, and observe in real-time how the tissue responds to the physical blows. For example, a tight pull on the sample mimics the distortion that would occur during a car crash. Using the data from these simulations, Morrison’s lab is studying how far the tissue can stretch without tearing, how many neurons are fired during the accident and how many cells die during and after the initial injury.

Other neuroscientists are impressed, but cautious. “Overall, this idea is a very good start, but is still in its beginning stages,” said Dr. Henny Billet, who studies the neurocognitive effects of stroke at Montefiore Medical Center. The next step, she explained, should be to study TBI effects on the brain in more life-like situations, as opposed to the carefully controlled environment of the lab.

Until then, Morrison left the audience with a word of advice: “Wear your seatbelt.”

4 Comments

There were no seatbelt s when I had my auto accident in 1969. I am a vietnam veteran. I have a tbi. I have results of pet/spect scan. I would like a dti. I live in Puerto Rico. When can I come see you?? Just bought airline tkts to NYC. Arrive 10/31/15. Scan done 5/2014.

I am currently having problems with short term memory recall and perhaps retention of mathematical equations and solutions. I am 52 years old and other people my age have better memory recall and retention than me. When I was twenty years old I had a parachute fail and fell free for an undetermined height and speed. It was a night tactical night jump and it just happened to be foggy with zero visibility. I was unconscious for a time, temporary paralysis. My T12 on down to my L3,4,5 s1 compressed fractures. I am currently have complications with these areas in my vertebrae but am wondering if my brain could have sustained damage however minimal it may have been and could it be affecting me now that i am older. Reference my short term memory recall and math reasoning and comprehension?

I guess it’s connected with the accident or something else. Any evidence for that injury accident?

I appreciate how real this post is. I appreciate it. A very realistic post. Making everyone aware how frightening can it be when somebody experience a whiplash. Thank you for sharing your views.