The ‘blackest black’ — for science and art

A record-breaking engineered material leaves no room for vanity

Hannah Seo • November 11, 2019

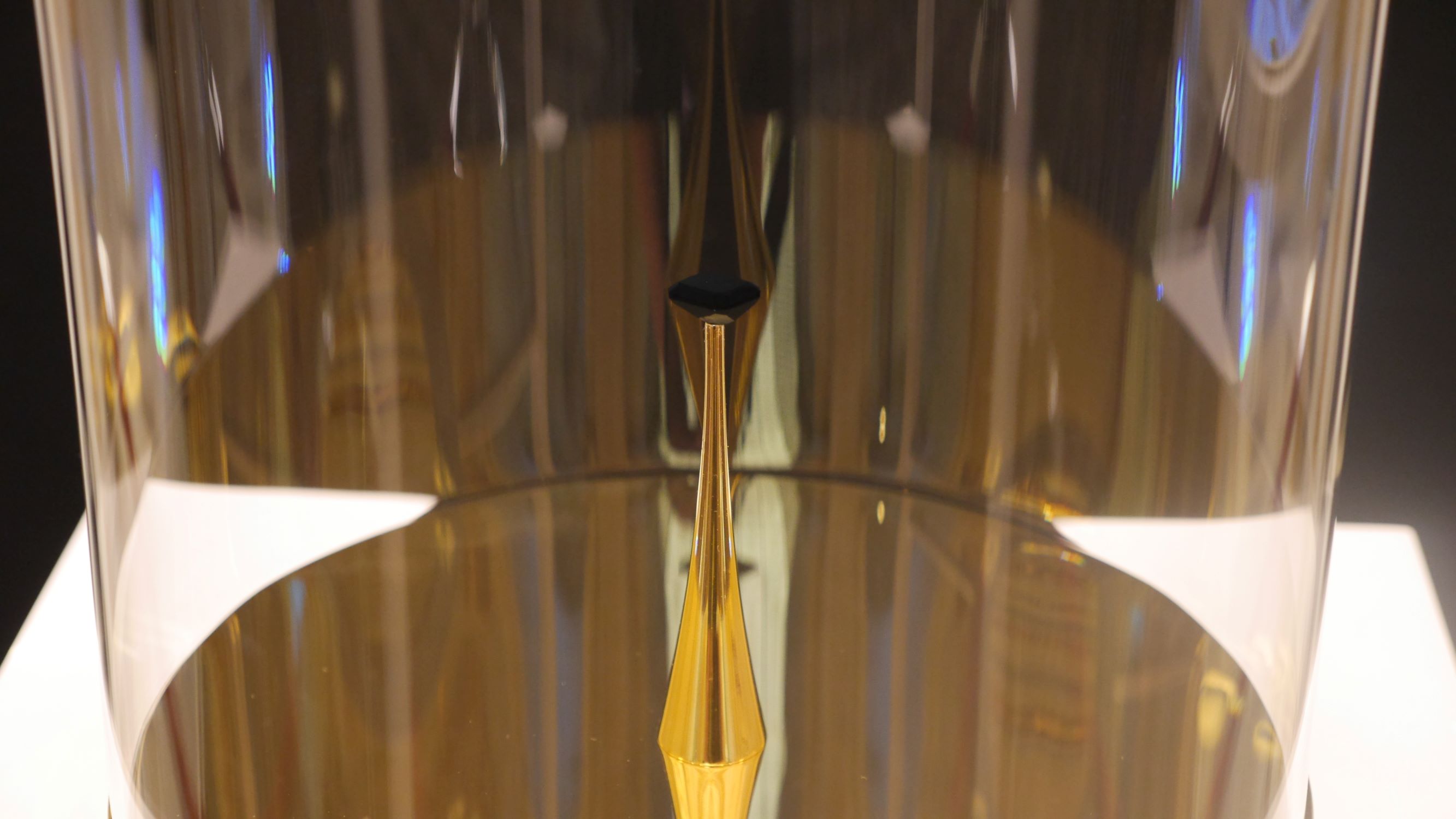

A $2-million, 16.78-carat yellow diamond covered with carbon nanotubes: “The Redemption of Vanity” [Credit: Hannah Seo]

An invisible diamond, worth $2 million, rests inside a large glass case in a gold-accented, Versailles-style conference room of the New York Stock Exchange. This newly created feat of art and cutting-edge engineering, The Redemption of Vanity, is a 16.78-carat natural yellow diamond rendered effectively invisible by a covering sheath of carbon nanotubes : single sheets of carbon atoms rolled up in a cylinder.

The diamond’s coating is not just black, it is the blackest black — the darkest color ever created. These carbon nanotubes have a structure that is 99 percent empty space, which allows the material to absorb 99.965 percent of all light that strikes it by trapping photons inside the architecture. The effect is the appearance of a void that lacks definition or reflection.

Diemut Strebe, an Artist in Residence at MIT and the creator of the piece, had been thinking about creating an art installation featuring a diamond swallowed by darkness since 2014. In 2016, she met MIT Engineer Brian Wardle who had been experimenting with CNTs; it was just a matter of waiting for the right material to emerge from his laboratory. Strebe acquired the hefty diamond through a donation by L.J. West Diamonds, Inc. — and a true donation it is: the growth process of nanotubes onto the diamond’s surface is irreversible.

On a recent visit to the stock exchange, Strebe stood in front of the display she affectionately calls a “tabernacle” and described the piece as a “denial of the seductiveness of the senses,” alluding to how the blackest black looks like literal nothingness. She points out the irony in coating a diamond, a luxurious crystal structure of carbon, with the ultimate form of darkness also composed of a different form of carbon. By forcing us to consider “carbon versus carbon,” she says, the art highlights how society assigns value to “arbitrary objects and concepts.”

After all, she adds, there is “no better place to contemplate value than at the New York Stock Exchange.”

Wardle and his students created the record-breaking material while experimenting with new configurations of CNTs. While many labs have been growing carbon nanotubes for years for various technological applications, Wardle’s lab developed a new technique yielding a light-smothering material — the blackest black yet.

Carbon nanotubes’ level of blackness depends on the structure you create, he explains. The structure of their CNTs happens to be 99 percent empty space, which is why they’re so good at absorbing light.

The newly nano-engineered material is likely to prove useful in machines such as telescopes and satellites that rely on precise calculations that might otherwise be altered by stray light. Simon Zeidler, a physicist at the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, uses ultrablack materials such as Vantablack as “beam-damps” to “lower down unwanted back-reflections and unwanted [light] scattering” in highly-precise ray detectors. Wardle’s material needs to be investigated, says Zeidler, adding that it will be interesting to see how this new carbon nanotube material compares to the shades of black in current use.

For now, though, the highest-profile application of the new blackest black is the artistic statement installed on Wall Street in September 2019.

Artist of The “Redemption of Vanity”, Diemut Strebe, examines her work. [Credit: Hannah Seo]

Strebe and Wardle have a second project in the works: House Kundmanngasse 19. Set for release within the next year, the upcoming project will be a 1:150 scale replica of the house designed by Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, also covered in the blackest black. The house, the pair hopes, will both mirror and challenge Wittgenstein’s attempt “to draw a limit to thought.”

Art informs science, says Strebe. This was an art-science collaboration, Wardle agrees, and we may never have investigated the optical properties of our new material if it hadn’t been for the influence of art.