Bridging science and culture with the Thirty Meter Telescope

How taking the right steps helped mitigate a 40-year dispute in Hawai‘i

Joseph Castro • January 18, 2011

Hawaiian creation chants tell the story of Wākea, sky father, and Papahānaumoku, earth mother, whose union resulted in their first child, the Big Island. On the island stands the dormant volcano Mauna Kea, which represents the island-child’s navel and symbolizes the Hawaiian people’s connection to their ancestors. Those ancestors are believed to be the Hawaiian gods, many of whom reside on Mauna Kea’s summit approximately 14,000 feet above sea level, the sacred spot where Wākea and Papahānaumoku now meet.

However, since the late 1960s, the Hawaiian gods on Mauna Kea have had to make way for a new set of deities: the observatories, the gods of astronomy. “Mauna Kea is the best site for [land-based] astronomy,” said Rolf-Peter Kudritzki, former director of the University of Hawai‘i’s Institute for Astronomy on O‘ahu. Mauna Kea’s combination of high altitude, low humidity and little atmospheric turbulence allows astronomers to get clearer images of the universe than they can from other locations around the world.

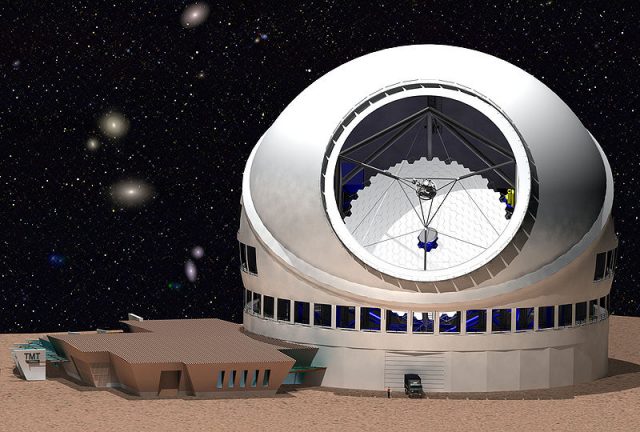

With 13 observatories atop the mountain, Mauna Kea is paradise on Earth for astronomers—a paradise that may soon grow more heavenly. If approved by Hawai‘i’s Board of Land and Natural Resources in February, the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) will become the 14th observatory to call Mauna Kea home once construction is completed around 2018. Housing a telescope mirror at least three times the size of any other on Earth, the TMT, sponsored by the California Institute of Technology and University of California, Santa Barbara, will easily outclass all other telescopes.

It’s no surprise, then, that Hawai‘i astronomers are enthusiastic about the project. Kudritzki is looking forward to directly observing planets around other stars, something no other telescope can do. Native Hawaiian astronomer Paul Coleman sees the TMT’s potential to promote community excitement about science. “[It’s] something we can really get our kids involved with,” Coleman said, adding that the telescope will show children that there is a future in science for them in Hawai‘i.

Despite the scientific buzz, however, not everyone is sold on the project. There’s a history of bad blood between the community and the observatories, a history not easily forgotten.

In 1968, the Board of Land and Natural Resources approved a 65-year lease to the University of Hawai‘i for Mauna Kea land above 12,000 feet. By the end of that year the university built the first telescope on the mountain’s summit, and the leased area was dubbed the Mauna Kea Science Reserve.

At first, “there wasn’t a whole lot of controversy,” said Stephanie Nagata, interim director of the Big Island-based Office of Mauna Kea Management, an organization created by the university in 2000 to oversee the reserve. In the early 1970s, the Hawaiian Renaissance—the resurgence of a distinct culture based on traditional Hawaiian values and beliefs—had only just begun, she said. As the movement grew, concern over the observatories spread and “more and more people began to speak out.” By the 1990s, protests against the observatories were in full force.

Environmental groups worried that construction on the mountain could damage native life, like the endemic Wēkiu bug, and that human waste from the building and use of the observatories could dramatically change the landscape. Cultural groups considered construction on Mauna Kea sacrilegious, arguing that it defiled the gods’ home and destroyed Hawaiian family shrines. Adding further insult to injury, the University of Hawai‘i initially denied Native Hawaiian religious practitioners access to sacred sites near the observatories.

Native Hawaiians also pointed out that the Hawaiian community receives no benefit from the observatories, despite Mauna Kea’s cultural history. “Whatever benefits are coming from these telescopes aren’t being allocated fairly,” said Miwa Tamanaha, executive director of KAHEA, an environmental group critical of the observatories.

More than anything else, people were outraged by the university’s failure to involve the community in its decisions. “At the end of the day it’s about process,” said Tamanaha. “Communities that care about Mauna Kea have really been starved for a process to grapple with the situation.”

Luckily for the community, the University of Hawai‘i learned its lessons. In response to protests—and a critical 1998 state audit of its handling of Mauna Kea—the university, in 2000, laid down a policy framework for responsible stewardship of the mountain’s cultural, environmental and scientific resources. Some five years later, the Mauna Kea management office, which was in charge of implementing the policy, began developing a comprehensive management plan to provide guidelines for future development projects atop Mauna Kea.

Although the community was involved in creating the new policies, people were still wary of additional observatories. Some wounds are difficult to heal. So when the TMT project first set its sights on Hawai‘i in 2006, many in the Big Island community were opposed.

An artist’s rendering of the TMT [Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons]

To improve public opinion, the TMT staff and some community members set out on an outreach campaign, which included visiting local schools, holding community meetings and waving signs. TMT members also tried to address community concerns. They completed an environmental impact study to ensure indigenous life wouldn’t be harmed; they chose a site that wasn’t culturally valuable; and they agreed to physically carry human waste down the mountain, rather than use a cesspool.

Additionally, the project pledged to give $1 million per year for the lifespan of the observatory—or at least until 2033 when the university’s lease ends—to the Big Island community for education, and promised to focus on hiring locals for staff positions. No other observatory on Mauna Kea made such promises.

Public opinion slowly improved. “In our first public meetings, if there were 40 people in the room, at least 30 were against [the project],” said Sandra Dawson, site-planning leader for the TMT. But in a recent meeting, “there were 120 people in the room and only 4 people spoke against the project.” Not a single detractor was native Hawaiian.

Richard Ha, a Big Island community member who assisted the TMT staff with their outreach endeavors, says that it was initially difficult to get people to commit to the project. They were afraid of speaking out in favor of the TMT, afraid of possible backlash from the rest of the community, he explained.

Ha, owner of Hamakua Springs Country Farms on the Big Island, believes that this fear lessened after he and a few other prominent community members, like Patrick Kahawaiola’a, president of the Keaukaha Community Association, created radio ads endorsing the management plan (and, by extension, future observatories) in early April of 2009. “That gave people the courage to be pro,” he said. About a week later, the Board of Land and Natural Resources approved the plan after listening to two days of public testimony.

The TMT project is now nearing final approval, with the Board of Land and Natural Resources set to vote on the TMT’s conservation district use permit sometime in February, according to TMT’s Dawson. However, despite efforts made by the TMT staff and the Office of Mauna Kea Management to address community concerns, small, outlying groups like KAHEA are still unhappy. Astronomer Coleman thinks that there will always be some people against new Mauna Kea observatories, “no matter what you do.” Dawson adds that those who are opposed seem more upset with the University of Hawai‘i than the proposed observatory. “I think that most are angry over things that happened in the past,” she said.

But in the end, management office director Nagata thinks that the TMT “really helped to bring the Big Island community together.” The TMT isn’t your usual story about the clash between science and culture; it’s a story about successfully finding a balance between the two.

5 Comments

Good article. The telescope will be good for everyone, so we should all appreciate the efforts of Mrs. Dawson and the rest of the TMT staff to clear the way for this wonderful achievement.

..just to remind those who care to listen that ESO’s ‘Extremely Large’ (42-meter mirror) telescope will actually be the world’s biggest AO-monster. :)

Joseph,

This feels a little like a PR piece for TMT. I also feel that much of the information I shared with you was a bit misrepresented. I believe deeply that the University of Hawai`i has still NOT addressed the fundamental issues of process.

“Luckily for the community, the University of Hawai‘i learned its lessons.”

(1) The comprehensive management plan that the University prepared in 2009 was done so only after they were taken to court and lost in 2007. The 2009 plan does not deal with impacts on the mountain from new development, and is specifically silent on development of TMT.

(2) The comprehensive management plan also does not address the issue of the state leasing and subleasing this land for $1/year.

(3) The Office of Mauna Kea Management implementing the 2009 plan, which Nagata represents, is an entity of the University. This means cultural and natural resource management is being handled by the lead developer of the mountain. We believe this is a clear conflict of interest.

In the end, this really is not about TMT, but rather, the history that TMT assumes when they chose Mauna Kea as the site for their project. This is about the University of Hawaii and the State of Hawaii and their neglect of their kuleana (responsibilities) with respect to our sacred summits — including Mauna Kea, Mauna Loa, and Haleakala. This is the fundamentally broken management paradigm, which so desperately needs to be fixed.

KAHEA is not a “small, outlying group.” Further, we are joined in our demand for a better process and a better future for Mauna Kea by Sierra Club, Mauna Kea Anaina Hou, Kanaka Scholars against Desecration, and hundreds of individuals on Moku o Keawe (Big Island) and around Hawai`i and the planet.

Miwa

Miwa,

Thank you for the comment. If KAHEA was misrepresented, it was not my intent. I’ve spoken with numerous individuals involved with the controversy and tried to weigh the evidence as fairly as I could, in the most space-conscious manner I could.

The article is primarily about the Thirty Meter Telescope, so I can see how you might view it as a “PR piece” for the project, as you put it. To be fair, however, TMT staff members took steps that were very different from other observatories that have been built atop Mauna Kea, prompting my interest in doing this article in the first place (for example, their attempts to get to know the Big Island community and the issues surrounding the mountain long before it was chosen as the site for the observatory).

While the comprehensive management plan is not perfect, it does appear to have addressed most of the issues the community raised. According to Stephanie Nagata, the plan was not developed in response to the Outrigger lawsuit you mentioned. Actual development of the plan began in 2005.

As I understand it, the $1/year figure you state was arranged simply to make the contract legally binding. You’re correct in saying that the plan does not address the leasing issue of the Mauna Kea land, though I think this particular issue may be out of the scope of the plan’s intent. The comprehensive management plan (and the Office of Mauna Kea Management) was created to serve as a guideline to manage existing and future activities atop Mauna Kea; it would seem that the leased-land problem is something that needs to be addressed by the Department of Land and Natural Resources.

Either way, the TMT actually tried to address this themselves with their $1 million per year donation, as mentioned in the article.

While the Office of Mauna Kea Management is an organization put in place by the University of Hawaii, that does not necessarily mean that it was developed to serve the university’s interests. In part, the university created the office to manage the Mauna Kea Science Reserve locally on the Big Island, rather than from Oahu. This allows for a greater interaction with the community. Also, as I am sure you’re aware, Kahu Ku Mauna advises the office on cultural matters affecting the Mauna Kea Science Reserve. The nine-member council members were chosen based on their “awareness of Hawaiian cultural practices, traditions and significant landforms as applied to traditional and customary use of Mauna Kea and their sensitivity to the sacredness of Mauna Kea,” as stated on the management office’s website.

As I’ve heard from my sources, the University of Hawaii has had a long history of neglecting their responsibilities with respect to sacred sties. It is very unfortunate that it has taken so long for any positive change to happen, but at least it is now happening. Paul Coleman said to me, and I tend to agree with him, that challenges to the telescopes by KAHEA and other groups are important in that they keep Mauna Kea from becoming “a city” of telescopes. However, only through continually working with those in the university and state—rather than against—will the damage done ever be rectified. A large problem, it seems, is that this is a very nuanced issue that must take into account many things, such as cultural concerns of the Hawaiian community, financial concerns of the state (particularly in these rough economic times), and the scientific future of Hawaii’s children. One can only hope that all concerns can someday be addressed; for now, at least, it appears there is a balance and there are forums for voices to be heard.

Joseph

I was drawn to this article after watching a documentary on the history of the telescope. I am neither a scientist nor an environmentalist by trade, but I am a former journalist and professor of journalism. I came to this site simply because my interest was piqued in Mauna Kea.

From a strictly journalistic perspective and without the benefit of your research, Joseph, the article is extremely well-written. I base this on the simple, empirical judgment that I was not swayed and I understand both points of view. The litmus test of integrity for me is that the information is there and I am left to my own judgment.

I think it is unfortunate that civilization, especially Western civilization, has become utterly bipolar. It seems impossible for some people to even tolerate those with diametric points of view, let alone understand them. Ironically, I blame the polarization on the so-called pundits of the very media that I profess. Debate has been reduced to a series of half-hour programs wherein blowhards with no substantial knowledge or resources yell at each other.

That is not to imply such is the case here (with due deference to Miwa), but it does make the job of the writer increasingly difficult with respect to maintaining a disinterest while writing an article.

I am ambivalent because I wish to both save the planet and discover the beauty of the universe simultaneously and with equal gusto, but I realize science and culture wiil often butt heads. This is my verbose way of saying kudos to you, Mr. Castro, for a noble effort in condensing a complicated controversy. (Pardon the alliteration)

Jeff