The taste of victory

An award-winning gustatory neuroscientist is using his discoveries to overcome a total aversion to fruits and vegetables

Madeleine Johnson • March 7, 2011

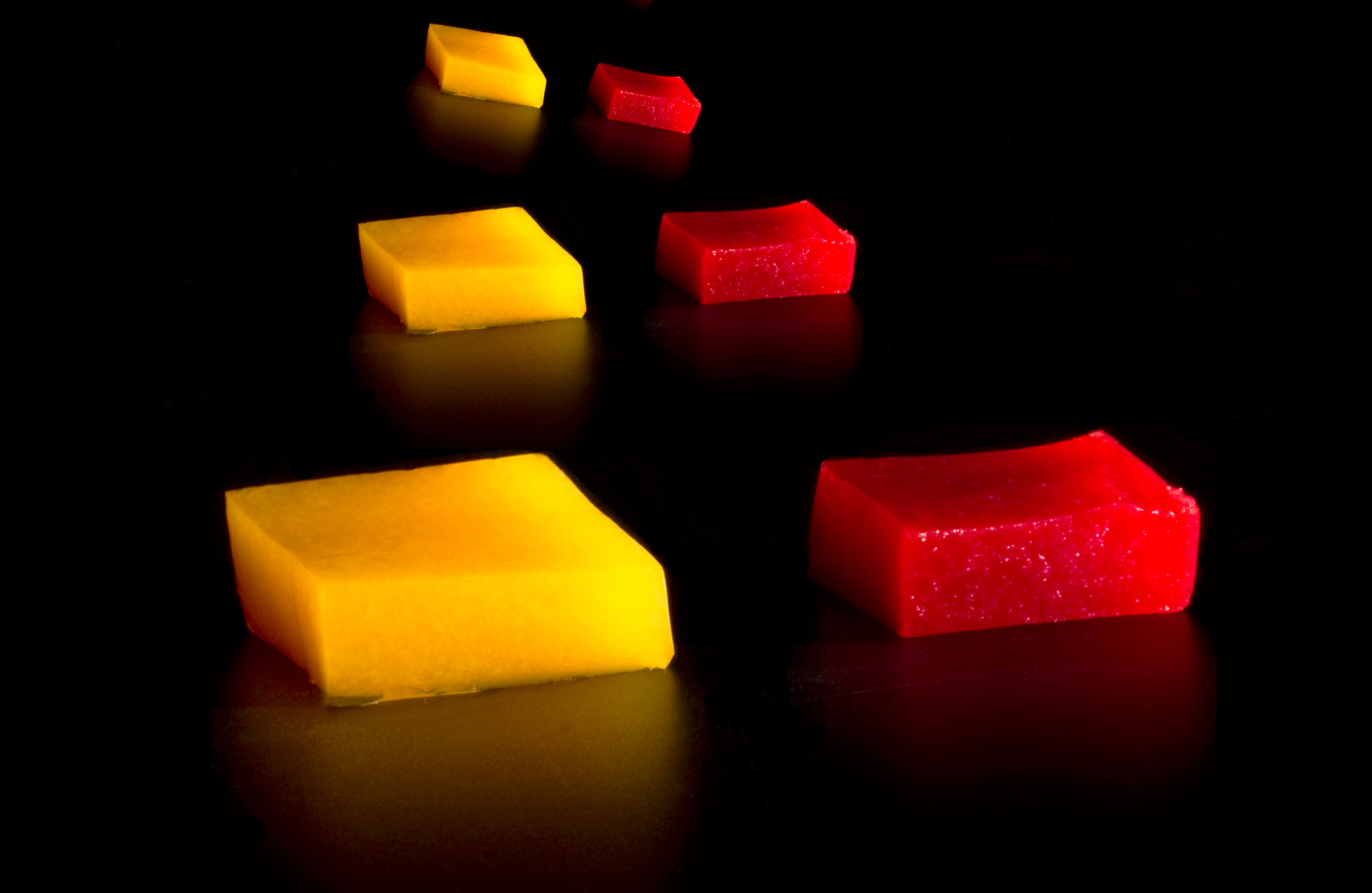

Surprise! The orange appetizer (on the left) tastes like beets. The red one (on the right) tastes like oranges. [Image Credit: Auldo Cornelissen ]

Much like a joke, a flavor can be delightful or disgusting, depending on when and how it is presented. Celebrity chefs know this, and instinctively take advantage of timing and expectation in some of their more experimental creations. Their “jokes” are no laughing matter; molecular gastronomy, the study of the science behind cooking, is big business. At The Fat Duck in England, currently ranked third best restaurant in the world, a four-hundred dollar dinner begins with a tiny appetizer, an amuse-bouche that purportedly plays with anticipation and surprise. Served side-by-side, two bright squares are introduced as orange and beet jellies. But the orange-colored gelatin tastes of savory yellow beets, and its red-hued neighbor tastes like sweet blood-oranges. This culinary quip exposes the powerful influence that preconception of a flavor has on its perception.

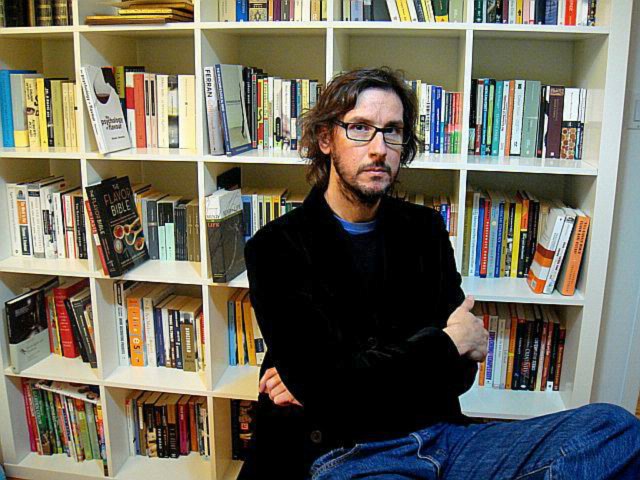

Alfredo Fontanini, 39, is a researcher at the State University of New York at Stony Brook who studies the way the brain processes such surprising tastes. He recently traveled to Washington, D.C. to receive the Presidential Early Career Award in Science and Technology for his contributions to the field of gustatory neuroscience. The award extends his lab’s funding from the National Institute of Health by one year, equivalent to almost a quarter-million dollars.

While preparing a talk to his department honoring his achievement, Fontanini excitedly fired emails back and forth with celebrity chefs. He wanted to include a recipe exemplifying gustatory surprise in his lecture, and was so persuasive and enthusiastic that he convinced one chef to share a top-secret creation involving watermelon and raw tuna.

In the gustatory cortex, a small in-folding located just about ear-level, the brain receives information from the tongue and interprets it, ultimately making a behavioral choice: spit or swallow. According to the dominant theory, information about what is in the mouth is added together in this region to create the sense of taste — salty, sweet, bitter, sour and savory flavors, in addition to spiciness, temperature and texture.

But Fontanini argues that tasting is more than just a simple summation of sensory data. His studies suggest that taste is created, rather than represented, in the mind, and that mental states — mood, anticipation, attention — have such an influence on this process that no two bites can ever taste the same. With a clever experiment, he has found a way to experimentally manipulate anticipation, surprising the brain with flavors.

In laboratory cages, rats drink water from inverted bottles with lick-spouts. Fontanini has shown that simply seeing the lick-spout causes a rat’s gustatory cortex to become excited in anticipation of tasting something. To get around this, he implants a tiny tube in the rat’s mouth. Through the tubing he can flash a pulse of flavor, either paired with a sound or not, while measuring the electrical activity in the brain.

By delivering an unexpected drop of sugar water, or salty water when the animal hears a tone that usually predicts sour taste, he can begin to see how preconception changes neural processing — and what surprise looks like. His experiments show that without cues to hint at an incoming taste’s identity, the gustatory cortex takes ten times as long to perform its analysis. Only the prejudicing information from other senses, thoughts and feelings makes it possible to decode what is in the mouth at normal speeds.

Neuroscientist Alfredo Fontanini studies the way the brain computes sense of taste. [Image Credit: Alfredo Fontanini]

Fontanini’s own career trajectory has been surprisingly rapid. While studying to be a psychiatrist at the University of Brescia, Italy in the mid 1990s, he became obsessed with the way the brain organizes its electrical impulses into circuits to encode information. He began reading textbooks in his free time, and essentially taught himself the basics of electrophysiology, the study of electrical signaling by cells in the brain. Upon finishing his medical degree, he switched gears and pursued brain research, persuading his PhD advisor at Brescia to let him do his dissertation work in an international laboratory of his choosing. After sending a slew of emails to high profile labs in the U.S., he was invited to visit the lab of James Bower at the California Institute of Technology. There, the slender Italian was smitten with the former hockey player Bower, whom he describes as a super intelligent ‘Big Lebowski.’

Fontanini picked up and moved 6,000 miles to Pasadena, where he thrived in the free-form intellectual environment of the lab. “I just provide the space to get into trouble,” says Bower. “If you don’t have the ability or motivation it’s not likely you will be successful.”

Fontanini proved himself both able and motivated. His dissertation project, completed in less than three years, was a “technical tour de force, which required great precision and care,” Bower recalls. He recorded electrical chatter from within neurons in multiple parts of a sleeping rat’s brain, while simultaneously manipulating the animal’s breathing rate with a ventilator.

Fontanini discovered that a particular pattern of very slow oscillation in the cortex, usually associated with memory formation, was locked to the pattern of the animal’s respiration. But this synchronization only occurred if the animal was breathing through its nose, not its mouth. In a characteristic leap in data interpretation that “requires mental fortitude and flexibility,” Bower says, Fontanini postulated that the ability of nasal breathing to synchronize slow-wave brain oscillations might be the mechanism whereby meditation has its effects on the mind.

In his post-doctoral work at Brandeis University in Boston, which he continues in his own lab at Stony Brook, Fontanini began uncovering the ways the brain creates taste. Yet despite all his knowledge, and a passion for technical stunts in cuisine, Fontanini has spent his life spitting out perfectly good fruits and vegetables. Since childhood, he has found the tastes of sweet and sour overwhelming. Growing up in Italy, his mama indulged little Alfredo’s taste aversion, and fed him a diet of mostly meat. His grandmother made him bulk quantities of tripe stew. His aunt would try to trick him into drinking banana smoothies, and he would vomit.

A few decades later, Fontanini theorizes that fruits and vegetables still evoke the same disgust for him as meat might to a strict vegetarian. Although he did not become a gustatory neuroscientist because of his taste aversions, per se, he is now using his knowledge of the brain to defeat his phobias.

Fontanini recently tasted a pear for the first time in his life. He says the juiciness was such a turn-off that he needed an accomplice to cut it. His wife Arianna Maffei, also a highly successful neuroscientist, indulged him and cut a small sliver for him to experiment. He reasoned that if he experienced the fruit with as many senses as possible, or as he says, “brought as many friends of the pear around the enemy of texture,” he might get over his revulsion. He spent time acclimating to the smell and appearance before letting it rest in his mouth and appreciating the complex sweet and sour flavors. He considers his experiment a success, and has repeated it with other fruits. The banana is now his friend, he claims, and “now I’m facing the peach.”

Fontanini hopes his laboratory data will help generate new ideas for the treatment of obesity and other appetite disorders. He is also collaborating with celebrity chefs to create new sensations in the field of molecular gastronomy. Whether he will be able to eat these creations remains to be seen. “I am relatively adventurous when it comes to crazy-looking stuff,” he says. “Yet, a single hint of fruit or greenery scares me.”

For an extra taste of Fontanini’s work, listen here: Rose Eveleth tells you what your brain sounds like when you eat a big meal.

The sounds of science by Scienceline

6 Comments

FANTASTIC article… the author has somehow captured every nuance of the science and the -tist….

DELICIOUS!!

Wonderful article. I’m glad he won the Presidential Early Career Award in Science and Technology.

Delectable; piques appetites of stomach and mind — a fine balance!

Too bad he can’t take my ex-roommate into a locked room and experiment on him. Before I kicked this ingrate (an old friend who had fallen on hard times) to the curb, I first tried beguiling him with many home-cooked standards: chili, spaghetti, omelettes, Chinese and Korean cuisine, soul food, homemade breads and cookies etc. Once he discovered I was using onions in the chili and spaghetti sauce — and ground turkey instead of ground beef… then witnessed ingredients that resembled vegetables or things like blackeye peas or rice in other creations, he actually stopped eating — didn’t even try anything that looked or smelled like it might have a vegetable in it. He didn’t complain, but instead actually began going door to door begging for food, telling people that I had no food in the house. Eventually people told me what he was doing, and not wanting to appear like a complete jerk I ended up spending thousands of dollars buying junk for him that he wanted: children’s sugary cereal, ramen noodles, lunch meat, cheese, white bread, gallons and gallons of milk, coffee (a pot a day), and little else. He refused to work or apply for food stamps so his $250-a-month food habit (plus many other challenges) came to a rude end. I am now happily back to living healthy on $80-$120 a month by myself. He is living at the homeless shelter, selling his $185 in food stamps for $90 so he can buy cigarettes.

April 9, 2011 at 8:22 pmI see you are interested in haivng an academic discussion about the definition of sentience. I am not; as I clearly know the difference between snapping a carrot and snapping a dog’s neck. I suspect you do, too, and are only posing these questions for kicks.We owe animals consideration and respect because they, like us, are sentient certainly. Because they have the ability to suffer and feel pain, as well as the ability to experience joy and pleasure. Because they are self-aware and are the subjects of their own lives and have an interest in not being used for human purposes. And it would be no more ethical to use animals who had been genetically altered to not feel pain than it would be to engineer zombie human slaves.Ultimately, the decision to be vegan comes down to deciding to not participate in the unjust and needless oppression of a whole class of beings (nonhumans) simply for the greed and pleasure of those in power (humans). I think this is something a self-proclaimed Marxist should be able to understand.