The migrant malady

Imported tuberculosis remains a concern to US health authorities

Madhu Venkataramanan • September 12, 2011

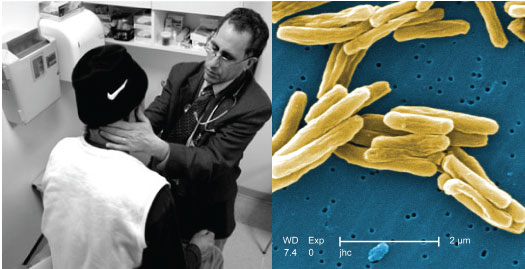

Dr. Allen Keller examines a refugee patient for diseases like tuberculosis, which is caused by a rod-shaped bacterium (pictured right). [Image Credit: Survivors of Torture, CDC]

A frightened man sat before the doctor, waiting patiently to be examined. As the doctor scribbled some notes, the man doubled over, heavy coughs racking his frail body. The doctor noted the coughs with rising alarm and immediately arranged for blood tests and a chest X-ray.

This was no ordinary patient: The man had recently escaped prolonged imprisonment and torture by the Chinese army in Tibet. A few days later, when the patient’s tests came back positive, the staff at the New York City clinic sprang into action. He had active, infectious tuberculosis. To limit spread of the rod-shaped microbes being released with his every cough, masked nurses isolated the Tibetan.

The diagnosing physician who described this incident is Allen Keller, the founder of the Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of Torture. The program provides medical and psychiatric treatment for victims of political violence and trauma. The New York City clinic has cared for more than 3,000 men, women and children from at least 80 different countries in the decade since its opening. Dr. Keller’s usually soft voice rose excitedly as he explained, “The physical, psychological and social factors are all interconnected.”

Tuberculosis: a profile

Indeed, tuberculosis, or TB, has always been described as the disease of the poor. It tends to thrive in dirty, overcrowded conditions, deep inside the lungs of people weakened by hunger and hardship. Refugee camps, prisons and makeshift homes are perfect settings for transmission.

Most of those who catch the TB bug develop a latent, non-contagious form of the disease that can last for a lifetime. This means the patient will show no outward symptoms of illness.

Latent tuberculosis bacteria are usually held in check by the body’s immune defenses. They could, however, waken at any time into a raging and contagious infection, like the Tibetan patient’s disease. This re-kindling could be due to a weak immune system, substance abuse, or concurrent diseases like HIV and cancers. To prevent active disease, doctors are supposed to treat patients with an antibiotic called isoniazid, while the disease is still dormant.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a tiny microbe that thrives on oxygen. Once inside its host, the bug hides in the lungs, where it is unsuspectingly engulfed by white blood cells known as macrophages. If the macrophages are unable to kill the microbes, the bacteria break out and set up shop in the lungs. This is now an active tuberculosis infection.

Pinkly rotting tissue is surrounded by white masses of martyred macrophages. Various immune cells close in, in a last-ditch attempt to wall back the expanding bacterial population, causing lung inflammation. If the microbial offspring manage to hop onto cells that travel around the body, such as red blood cells, they can hitchhike through the blood to the stomach, liver and spleen. Eventually, tuberculosis kills a person by boring holes in body tissues, and causing organ failure. Two million people succumb to tuberculosis annually. It is the most successful infectious killer on Earth today.

The bacilli bounce between people with ease, when they spit or cough. A few hours on a packed airplane is all the bugs need to wreak havoc. Tuberculosis is most common in the developing world, specifically Southeast Asia and parts of the African continent, but it has a wide distribution, from the tropics to the Arctic.

In the United States today, about 10 to 15 million people harbor a latent TB infection. Over half of them are immigrants and refugees. Of these, about 10 percent will go on to develop active TB over the course of a lifetime.

The refugee problem

Every year, hundreds of thousands of displaced Tanzanian, Bhutanese, Iraqi, Hmong and Burmese families enter America, unknowingly harboring this sleeping contagion. The federal health authorities and American physicians are all extremely concerned about importing tuberculosis into the country, because it’s difficult to account for illegal immigrants.

“It’s not an extremely rare event that people fly in with undiagnosed TB,” said Drew Posey, a physician in the Division of Global Migration and Quarantine at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “There has to be constant vigilance.”

In his 2003 book Timebomb, physician Lee Reichman warned that the current global environment is ripe for a tuberculosis epidemic.

The key ingredients of a successful TB outbreak, he wrote, are the rise of HIV infections, a lax attitude towards treating latent TB, ballooning population sizes and loose immigration laws. “You can’t close the borders, or keep [refugees] out,” said Dr. Reichman in a phone interview. “The solution is to have better tuberculosis control.”

Howard Markel devotes a chapter of his book When Germs Travel to the 1980s tuberculosis terror in New York City. Manhattan in 1979 mirrored Dr. Reichman’s outbreak conditions almost exactly, with “a boom in immigration from nations where TB is common,” wrote Markel. Tuberculosis’s dramatic comeback cost a laid-back New York City one billion dollars in damage control, according to Markel.

The superbug hits close to home

What’s really worrying to global governments is the speedy evolution of the original, treatable bacterial strain into virulent versions of its initial form.

The “multidrug-resistant” strains can evade two of the key drugs that are commonly used to treat the disease — isoniazid and rifampin.

The year 2006 saw the rise of a TB superbug in South Africa, termed “extensively drug-resistant TB.” This strain is resistant to almost all the elaborate cocktail of drugs that are currently used. Although chemotherapy and a toxic second line of drugs are available to treat these patients, death rates and drug costs both skyrocket, said Dr. Posey.

These resistant mutants may seem like a vague and distant dread, but in 2004 the bugs landed very close to home, making Dr. Reichman’s prediction much too real.

The story begins when the United States offered to resettle 16,000 Hmong refugees living in a camp in Thailand. As the families arrived in California, local authorities screened them according to routine CDC protocol for common conditions, including hepatitis, tuberculosis, HIV and malnutrition. Since all refugees are expected to be pre-screened for these diseases before they get on a plane, the incoming test results were a shocker. Doctors diagnosed 37 cases of active tuberculosis, of which at least four were multidrug-resistant.

Sputum samples of refugees waiting to travel from Thailand were screened more carefully and drug-resistant TB cases were confirmed. “We haven’t seen any situation of this magnitude, where we were basically importing drug-resistant TB into the country on a plane,” said Dr. Posey.

The situation was given “outbreak” status and all refugee flights were halted while an expert team of CDC scientists, headed by epidemiologist John Oeltmann, flew to Thailand to curb the contagion.

Cultural baggage: a unique medical issue

Treating a tightly-knit foreign community for a highly infectious disease in an overcrowded refugee camp came with a unique set of hurdles. Apart from administrative and cost issues, “There were lots of … language and cultural barriers,” said Oeltmann.

The Hmong people have traditional beliefs, especially medical mores, which make them distrustful of western doctors. “There were rumors that this was all a big fib so they wouldn’t be allowed to go to America,” said Oeltmann; these families had been living in the Thai camp for sixteen years and “most had been waiting a lifetime to finally get over to the States.” The older Hmong resisted the tuberculosis pills far more strongly than the younger inhabitants of the camp. “We struggled with that,” said Oeltmann.

Socio-cultural issues like these are tightly entwined with tuberculosis medicine in the United States. The Tibetan patient with TB in Dr. Keller’s torture victim clinic went on to illustrate this point poignantly.

The man had been isolated in a sterile room to treat his TB when, “I got a frantic call from a nurse saying he had barricaded himself in his room,” said Dr. Keller. The doctor rushed over to understand the Tibetan’s panic and calm him down. Apparently the man had peeped outside his window at Bellevue Hospital and seen a patrolling Chinese-American policeman. The police uniform, combined with the patient’s isolation, had triggered terrifying flashbacks of his imprisonment by the Chinese.

“It taught us that now anytime we have to isolate [persecuted refugees] for TB, we should talk to them and explain why they are in a room by themselves and how it is very common at Bellevue that there are police,” said Dr. Keller.

Tighter screening procedures

The Hmong outbreak also led to a tightening of tuberculosis screening laws. “The screening was not as sensitive back then, it didn’t catch 100 percent of all people who had tuberculosis,” said Oeltmann. “Following this event, some changes were made to the screening to make it more sensitive.”

Testing for active TB usually involves a chest X-ray or a sputum sample analysis. What the CDC acknowledged after the Hmong incident was that sputum samples can sometimes be negative when a patient really does have tuberculosis. The most foolproof method is to culture the sputum on special media and look for the live bacilli under a microscope, although it takes a lot longer. This way, the bacteria can also be tested for drug susceptibility.

“Ultimately, the screening was changed to include cultures being performed, even after negative sputum tests,” said Dr. Posey. Since then, the CDC has apparently seen a huge improvement in diagnosis. The new culture tests have also allowed researchers to tailor drug treatments to an individual patient’s needs, according to Dr. Posey.

Local TB prevention: a case study

At a grassroots level, New York, like other states, sponsors hospitals to accept refugees from neighborhood charities and treat them for TB. The Heritage Health Center in Washington Heights is the newest addition to the city’s refugee clinic list. The center began accepting refugees in early 2011 and has seen a total of 10 patients, said the director Alvaro Simmons in March.

A tall, solemn man with greying hair and a soothing voice, Simmons was happy to show off his clinic. The exam rooms, painted a bright blue and yellow, were filled with friendly clutter, and nurses in cheerfully patterned uniforms fussed over the foreign patients in the sunny waiting room. Simmons said they had seen three patients who showed up positive for latent TB after a standardized skin-prick test. “We’ve been aggressive in treating latent TB,” he said. “We immediately start them on prophylactic medication.”

Contributing to better TB control worldwide

Despite better screening both overseas and locally, Dr. Keller said, “There are estimates that there are 400,000 torture survivors in the US, and whether they’re all getting screens is a mystery.”

Drew Posey of the CDC acknowledged that a fear of increased global drug resistance is driving TB treatment and screening changes. So the risk of escalating global tuberculosis rates has led to cooperation between the American government and international tuberculosis authorities. “We are trying, in some ways, to make a contribution to broader TB control in the world,” Dr. Posey said.

As for the Tibetan refugee with whom this story began, he now runs a program for other exiled Tibetans like himself, helping them to cope with the bewildering details of daily American life. Free from his troubled past, he has been granted permanent asylum in the United States and, after months of treatment, is finally free of his tuberculosis.

2 Comments

I am so surprised you were allowed to mention the negative contribution of immigration regarding the spread of communicable diseases. You know you are not allowed to depart from the “immigration good- those that want less immigration bad” narrative. Good luck with your career now.

Keep repeating-

We are a nation of immigrants!

Diversity makes us stronger!

We can never have enough diversity. This article is radical right-wing racist propaganda designed to vilify the multicultural wonderland in which we all now live. More third-world immigrants can only make us better and stronger. The writer of this vile piece should be severely castigated for his insensitivity and lack of tolerance.