Need a Tannenbaum? Ask Mandelbaum

Climate and soil explain the country's varying tree preferences

Ryan F. Mandelbaum • December 13, 2015

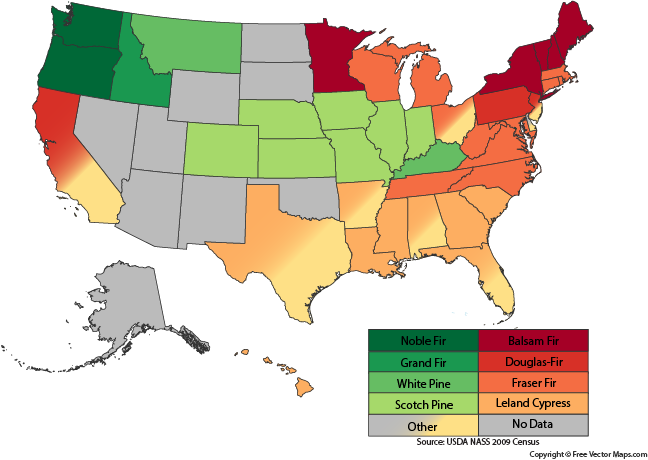

Favorite Christmas trees in each state, as reported to the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 2009, the most recent year available. In states marked with a yellow gradient, the most popular tree was listed as “other” in the USDA census. The alternate color on some states is for the second-most popular species in those states. [Blank Map courtesy of FreeVectorMaps.com]

As a boy raised in a Jewish household on Long Island, I always associated Christmastime more with the scent of Chinese takeout than with the scent of pine trees. While I don’t celebrate the holiday, for millions of Americans, selecting the right Christmas tree is a family tradition. What you might not know is that the kind of tree you take home likely depends on where you live.

The American Christmas tree industry, with its hugely popular product, is worth over $1 billion a year, so the U.S. Department of Agriculture takes a Christmas tree census to help farmers track the most popular varieties of tree in each state. The results are intriguing: While the West isn’t the best for a cypress, for example, and a fir will wither in the desert, the Midwestern clime is fine for a pine.

Here’s a region-by-region overview of America’s Christmas trees:

The West

The Pacific Northwest dominates the yuletide tree market, exporting the noble fir, grand fir, white pine and Douglas-fir. High elevations and moist, cool-but-not-cold air create the perfect growing conditions for these trees. They also fare better growing on slopes too steep for a sleigh to land on, like those in the Cascades and Rocky Mountains.

Oregon is the largest Christmas tree exporter in the country, according to the National Christmas Tree Association. In fact, another name for the state’s most popular tree, the noble fir, is simply “Christmastree,” according to the USDA. California’s climate is diverse enough for many Christmas tree species, but the current drought has caused Californians to rely on neighboring Oregon growers for trees, said Jamie Sevilla, manager at the Pronzini Christmas Tree Farms in Salem, Oregon. Pronzini’s farmers sell Christmas cheer — and trees — on six lots in Northern California.

“As far as the drought, our sales actually benefit,” said Sevilla. “People don’t want to come out in the rain.”

The Midwest

Scotch pine, which has the broadest range of any pine tree in the world, dominates the Midwestern states. The region’s climate and wide temperature range, as well as flat or rolling land and sandier soil, are ideal for this tree.

The Scotch pine’s Christmastime aroma and ability to retain needles, two qualities of Christmas trees my Italian godmother often complains about, make it one of the United States’ most planted Christmas tree species according to an About.com poll, even if it’s not always consumers’ first choice.

In the northernmost edge of the Midwest, meanwhile, farmers favor trees like the balsam fir and the Fraser fir. These trees require the colder temperatures provided by states with climes closer to Santa’s North Pole estate, like Wisconsin, Michigan and Minnesota.

The Appalachians

Oregon may be the US’s biggest tree exporter, but the most popular East Coast tree is the Fraser fir, which mostly grows in the Appalachian Mountains.

“The [Fraser fir] has the best fragrance of all types of Christmas trees, and holds its needles the longest,” even longer than the Scotch pine, said Scott Pressley, a grower in North Carolina. The tree helps garner North Carolina the number two spot in exporting Christmas Trees, according to the USDA.

Two of the Fraser’s genetic cousins, the white pine and Douglas-fir, are popular trees in Kentucky and Pennsylvania, respectively. However, with just 48,000 white pines in Kentucky and 7.5 million Douglas-firs in Pennsylvania, these states’ Christmas tree lights don’t shine nearly as brightly as North Carolina’s inventory of 37 million Fraser firs in 2009.

The Northeast

Like the Pacific Northwest, the Northeast has moister and cooler air, with a rugged landscape and well-drained soil. Instead of the noble or Douglas-fir, Northeastern growers prefer the balsam fir, which would be the backdrop of the white Christmases you’d dream about in Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire and upstate New York.

The balsam fir’s dark green color and strong fragrance make it an especially popular Christmas tree. Additionally, it is a very hardy tree that can thrive well in the shade, which makes it the seventh most abundant tree in the U.S., according to the North Carolina Cooperative Extension. If a tree grows well in the shade, it will thrive even if another tree is in the way, while less shade-tolerant trees would wither without the sun.

Further south, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Massachusetts and Rhode Island grow warmer weather trees, such as the Fraser fir and Douglas-fir.

The South and Hawaii

Most Christmas trees are firs or pines, which thrive best in environments more suited for Santa Claus. The Leyland cypress, however, doesn’t mind the moist, warm climates and sandier soils of the Claus’ vacation spots: The South — and Hawaii, too. As a hybrid of the Alaskan cedar and the Monterey cypress, the Leyland cypress is sterile and thus must be grown by planting a cutting from a parent tree. Even so, growers keep planting the Leyland and its newer, scentless cousin, the Murray cypress, because consumers generally favor it over the popular Fraser firs imported from nearby states. Another home state advantage: the increased popularity of cut-your-own tree farms.

“People enjoy coming as a family and cutting [a tree] down,” said Dan Raulston, president of the Georgia Christmas Tree Association. “That’s what we sell, as opposed to just the tree itself.”

So while wrapping your presents this year, take note of what kind of tree you have and where it came from, because Santa might be using it to remind himself where he is!

2 Comments

Great piece

I love the title of your piece – very clever!! Do the artificial trees sold in each area correspond to the trees grown in the region? Probably not, but it’s an interesting idea to make them regionally authentic, but let’s get real, there’s not much authenticity in a synthetic tree! Great piece!!