Here’s why deregulation won’t put miners back to work

Donald Trump’s energy policy is unlikely to fix coal’s economic woes or public opinion problem.

Eleanor Cummins • January 13, 2017

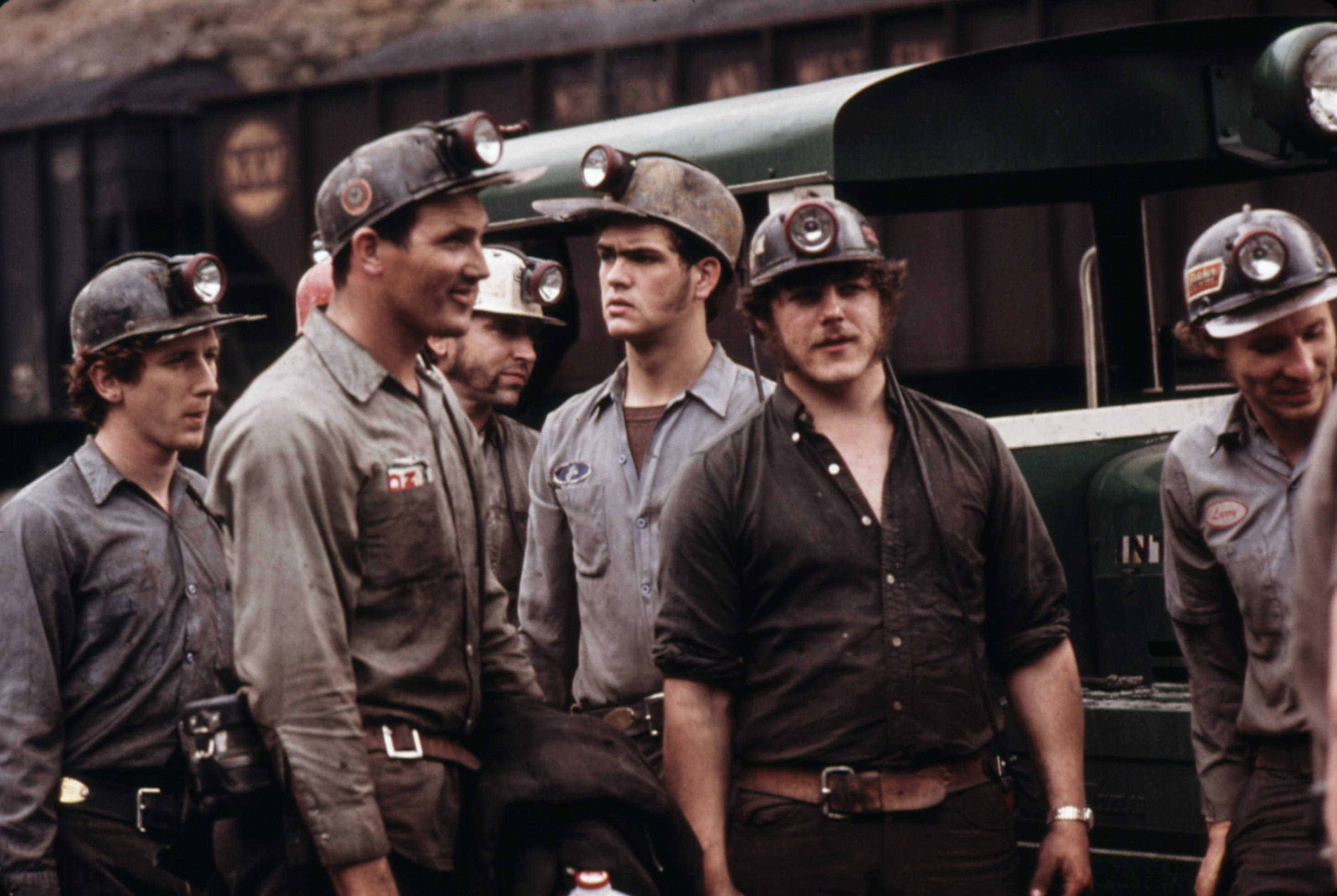

Coal is our most reliable energy source, but it’s also the most carbon-intensive. [Image credit: Wikimedia Commons | CC0 Public Domain]

To pinch a piece of coal is to hold the history of the industrial revolution between your thumb and index finger.

Used to power industry in 18th century England, coal has remained a mainstay of modern life. It is easily incinerated and today provides about a third of America’s energy.

But the glint of coal quickly fades and the black residue slowly covers the soft pads of your fingers and folds itself into the fibers of your shirt as you try to rub it away.

Because that’s the thing about coal — it’s dirty. It’s perhaps the dirtiest source of energy on Earth. For all its reliability and near-omnipresence, it coats the roofs and winter caps of people below the smokestacks. Coal burning is the largest source of carbon emissions from electricity generation in the United States, responsible in no small part for our rapidly warming world.

Increased understanding of the danger coal presents to both people and the environment has coincided, rather unsurprisingly, with a marked decline in the industry. The price of thermal coal, used to heat homes and offices, has tanked, going from $80 a ton in 2011 to around $40 a ton today. Five major coal companies with extensive operations in the United States filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2015 and 2016. Together, those companies lost $30 billion in stock value. In addition, 31,000 coal mining jobs have been lost since 2009.

Coal mining and its advocates, including President-elect Trump, blame strident environmental regulation for this rapid decline. Economists and lawyers, however, attribute coal’s downfall to other market factors, including the rise of natural gas and a growing preference for renewable energy sources such as wind and solar.

Regardless of where the blame is placed, most experts agree that coal will not be making a comeback.

“It’s been devastating, frankly,” Bill Raney, president of a trade group called the West Virginia Coal Association, says of the Obama era. The way Raney sees it, modern America was built off the backs of coal miners, and now the country’s moving on without them. “I have searched my soul to try to figure out why the government would want to take professional coal miner’s jobs.”

Raney believes the industry was brought down by the Obama administration’s negative attitude toward coal. Raney and his coal association endorsed Donald Trump because he promised to be different. Some supporters hope Trump will repeal the Clean Power Plan and the Mercury and Air Toxic Standards Act and undo other Obama-era regulation in order to bring back jobs.

The Clean Air Act was amended in 2015 to include the CPP. The CPP’s purpose is to reduce carbon emissions created by energy production. In the United States, that means reducing American reliance on coal, which emits more carbon than any other energy source in the country.

However, assessing the true impact of the CPP on the coal industry has been difficult because the law hasn’t gone into full effect and is currently being contested in court. Nearly half of states are suing for the right to ignore the federal government’s guidelines.

If Trump repeals the CPP — or if it isn’t upheld in court — states that are ideologically opposed to carbon reduction will be free to burn as much coal and other carbon-intensive fossil fuels as they want.

While coal may continue to burn in states like West Virginia, experts say most cities and states will likely follow through with their own carbon reduction plans even if federal oversight disappears. “With or without the clean power plan, this is where we’re going,” says environmental lawyer James Van Nostrand. “This is where economics are taking us. The government’s not making us do this.”

The Mercury and Air Toxic Standards Act, meanwhile, has required companies reduce the quantity of toxins released from their coal-fire smokestacks — and for good reason. Mercury is especially harmful to the environment. After being released into the air from a smokestack, some mercury particles fall to the ground where they pollute waterways and sow the seeds of acid rain.

Restrictions invoked by MATS, which went into effect in late 2011, did cause a number of coal-burning power plants to shut down. “There are a number of those plants — mostly ones that were built in the 1950s and 60s — that said, ‘Look we’re so old, we’re so inefficient, it’s not worth it.’ So you had a big wave of retirement,” says environmental engineer Daniel Cohan.

But repealing MATS now wouldn’t put retired plants back online, he says. “That train’s left the station,” Cohan says. So if Donald Trump repealed MATS, it could have important environmental consequences but little economic reward.

What’s more, the majority of coal-powered plants continued firing even after MATS was implemented, according to Cohan. And those that are still in production are being used less than half the time, Cohan says, suggesting that some other force is reducing the demand for coal-based electricity.

“Yeah, there is a war on coal but you have the wrong aggressor,” says environmental economist Robert Godby from his offices at the University of Wyoming. “The war on coal was declared by gas.”

In the few years, advances in hydraulic fracturing — more commonly known as fracking — have released unexpected bounties of natural gas, making it cheaper and more reliable than ever before. Utilities, which supply energy to cities, jumped on board and in April 2015 natural gas surpassed coal generation for the first time.

Simple economics, then, will likely will make Trump’s 100-day plan, already criticized for being rife with false promises, particularly disappointing for coal miners.

The plan states that on his first day in office, Donald Trump’s fifth act will be to “lift the restrictions on the production of $50 trillion dollars’ worth of job-producing American energy reserves, including shale, oil, natural gas and clean coal.”

But experts like Godby, the environmental economist in Wyoming, think a federal push to increase fracking and natural gas production would only continue to push natural gas prices lower, making coal an even less attractive energy source.

“You know, Wyoming’s best candidate was Bernie Sanders, at least… in the short term,” Godby said of the former presidential candidate, who is a fervent anti-fracking advocate. “If he banned fracking, that would be the greatest thing for coal.”