The end of biomedical research on U.S. chimps may imperil their wild brethren

Chimpanzee research was once done for the benefit of humans. Now, some researchers think it’s essential for saving the great apes.

Mark D. Kaufman • February 17, 2017

There’s an Ebola vaccine for humans, but not for great apes – all of whom are endangered. [Image credit: Flickr user Tim Parkinson | CC BY 2.0]

In the dense woods of Northeastern Louisiana, Penny, a 52-year-old chimpanzee, doesn’t let age discourage her – she’s an avid climber of the forest’s lofty conifers. After living for decades as a captive animal in a treeless laboratory, Penny was retired to Chimp Haven in 2011, a spacious sanctuary for retired laboratory chimpanzees. And Penny is hardly alone. She lives here with some 300 other chimpanzees, and after being federally emancipated from research colonies, hundreds more are on their way.

It has been over a year since the National Institute of Health ended its chimpanzee biomedical research program, which experimented on chimpanzees in efforts to advance human medicine. The end of this invasive research, while inarguably fair for apes like Penny, has some researchers alarmed – not for humans but for wild apes.

Africa’s great apes are in a bad place. Their meat fetches a high price and their forest homes are being engulfed by swelling human communities. Both chimpanzee and gorilla populations show catastrophic declines. In less than two decades, the chimpanzee population in Gabon was slashed in half, and nearly 80 percent of Grauer’s Gorillas disappeared in a single generation, dropping the population to just 3,800 individuals.

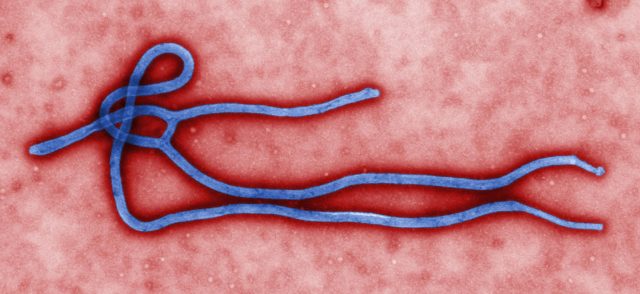

But yet another culprit – invisible and insidious – lurks in the African woods and threatens these fractured, endangered populations: infectious disease. It can come in the form of the ruthless Ebola virus, which has killed an estimated one in three great apes since 1990. And it can also come from an increasingly present source: humans, who pass deadly respiratory diseases to genetically similar animals. There is a solution – vaccination – but some scientists think the end of the National Institute of Health research program is hampering conservationists’ efforts to develop and test effective vaccines. And time might be running out.

Ebola may soon emerge in the dead center of ape country – the central and eastern parts of the Republic of the Congo, says Peter Walsh, an ape researcher at the University of Cambridge. Walsh tracks the deadly virus, identifying where it has sprouted up before and where it’s likely to emerge next. It’s carried around Africa by fruit bats, he says, and it might strike humans next, or it could strike apes. An outbreak last surfaced in 2014, wiping out over 11,000 people in West Africa. Its effects were so ghastly that President Obama committed 3,000 American troops to help contain the outbreak, which had spread to United States and stirred panic. Recognizing the inevitably of another wave of disease, scientists developed a vaccine for humans.

The Ebola virus is a potent killer of both humans and great apes, and the symptoms are grim for both types of primate: vomiting, diarrhea and bleeding from the mouth or nostrils (commonly from the nostrils in apes). [Image credit: CDC Global | CC BY 2.0]

But no effective vaccine exists for apes, which is the reason for Walsh’s urgency. “If we don’t find a vaccine now, then when it becomes vital, we won’t be able to do anything about it,” he says.

Vaccinating apes does not mean that Walsh and other brazen conservationists plan to walk through the jungle shooting unassuming gorillas with vaccine-filled darts. Rather, Walsh wants the apes to eat the vaccine. “To deliver it orally is the ultimate objective,” he says. This means finding bait that apes will find palatable and that will remain effective, even after cooking on the warm jungle floor, in wait for a hungry ape.

But without the ability to properly test it on chimpanzees – meaning feeding vaccine-laden bait to apes in a controlled laboratory setting – it’s difficult to know if the vaccine will work in the wild. This means Walsh has to do more guessing. “It becomes much more expensive, speculative and less safe, if we don’t use captive chimpanzees,” he says.

For instance, says Walsh, if he comes upon a colony of ailing gorillas in the deep jungle, he’ll have to wonder, “Are they sick because I gave them the vaccine, or are they sick because of something else?” Like any drug, the experimental bait may have harmful side effects.

For Walsh, the hope of using captive chimpanzees for research has vanished, even though hundreds of chimpanzees remain captive behind glass walls and metal bars all over the United States – in zoos. But zoos aren’t just good at keeping animals in – they can easily keep researchers out.

In 2015, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife service listed captive chimpanzees as endangered, like their wild counterparts in African jungles. This change in status gives captive chimps more protection, including a prohibition on biomedical research, unless researchers receive a heavily scrutinized permit from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Even if the federal government were to issue Walsh a permit, he is certain that no zoo would allow biomedical research on its chimps, fearing the negative public perception associated with experimentation upon these endearing, lively animals. “The problem is that everyone is so spooked now that nobody will allow it,” says Walsh.

Apes in zoos, however, are already subjected to needles and vaccines, so some researchers question the zoos’ reluctance. “Any good zoo is already giving their gorillas a full physical every year, drawing blood and vaccinating them,” says Chris Whittier, who studies conservation medicine at Tufts University. “All we’re talking about here is giving them an additional vaccine.”

Across the sea, in Africa, there are thousands of captive apes in sanctuaries that collectively make up the Pan African Sanctuary Alliance (PASA). But here too, vaccine research is not easily accomplished, simply because it’s not a goal. The apes here have been emancipated from horrific past lives, and after freeing them from their captors – often poachers – PASA sanctuaries are intent to protect the animals from human exploitation.

“If a researcher goes to a sanctuary with the attitude that the animals are there for the researcher’s convenience, rather than that they’re highly intelligent animals who were rescued from cruelty and suffering, they’ll be met with resistance from the sanctuary personnel,” wrote PASA executive director Gregg Tully, in an e-mail from Uganda.

Perhaps the greatest hurdle to medical research at PASA is the strict requirement that any research done on an ape has to directly benefit that specific ape. This would likely exclude Walsh’s research, which aims to help endangered apes outside the sanctuary walls. “These [sanctuary workers] care deeply about the welfare of chimps,” says Alex Rosati, a Harvard evolutionary biologist who studies gorilla cognition at different PASA sanctuaries. “Anything seen as decreasing their welfare is considered too high a cost.”

To Walsh, this creed clashes with the goal of conservation. He is fixated on dodging a dire future for the great apes – because this future holds more perils than just Ebola – specifically, diseases from us.

As more people come closer to apes, particularly because of tourism, more apes are being exposed to “the kinds of stuff that flies around the world in a plane that might give you a mild infection,” explains Walsh.

And for apes, these respiratory diseases are deadly. The Jane Goodall Research Center showed they are the number one cause of death in Gombe National Park, Tanzania, where people frequently get close to the animals.

Although researchers like Tuft University’s Whittier think it’s still unclear if tourists are passing such a high number of diseases to apes, he acknowledges that it wouldn’t be surprising it were happening. “The average mountain gorilla is sitting down for breakfast with eight perfect strangers everyday. Most people don’t have that sort of contact with people.”

But to Whittier, the threat of Ebola is not debatable.

“The risk of Ebola is real,” says Whittier. “If we had gorillas and chimpanzees that started dying by the thousands, like they did in the nineties, then it would be nice not to be where we are now, wondering if the vaccines are safe and effective.”

Whether this research will ever happen on captive chimpanzees remains uncertain. This challenges Walsh’s efforts, but hasn’t stopped them.

After completing work on an oral vaccine in the lab, Walsh plans to bring it directly to the jungle in either April or July 2017 and test it on the wild chimpanzees and gorillas he intends to save, though testing drugs on these creatures in an uncontrolled environment comes with uncertainty and risk. Lacking the ability to draw blood to see if the vaccine works, Walsh will have to analyze fecal samples he collects in the wild, which is time consuming, less precise and inconvenient.

But to Walsh, performing challenging research is preferable to the grim future that awaits the diminishing great apes. And he’ll keep advocating for the merits of biomedical research on chimpanzees, contentious as it is.

“I wish the world was very simple and everything would be black and white, good and bad,” says Walsh. “But that’s just not the way it is.”