Nuclear suburbs

The hidden nuclear history of suburban Los Angeles

Harrison Tasoff • August 18, 2017

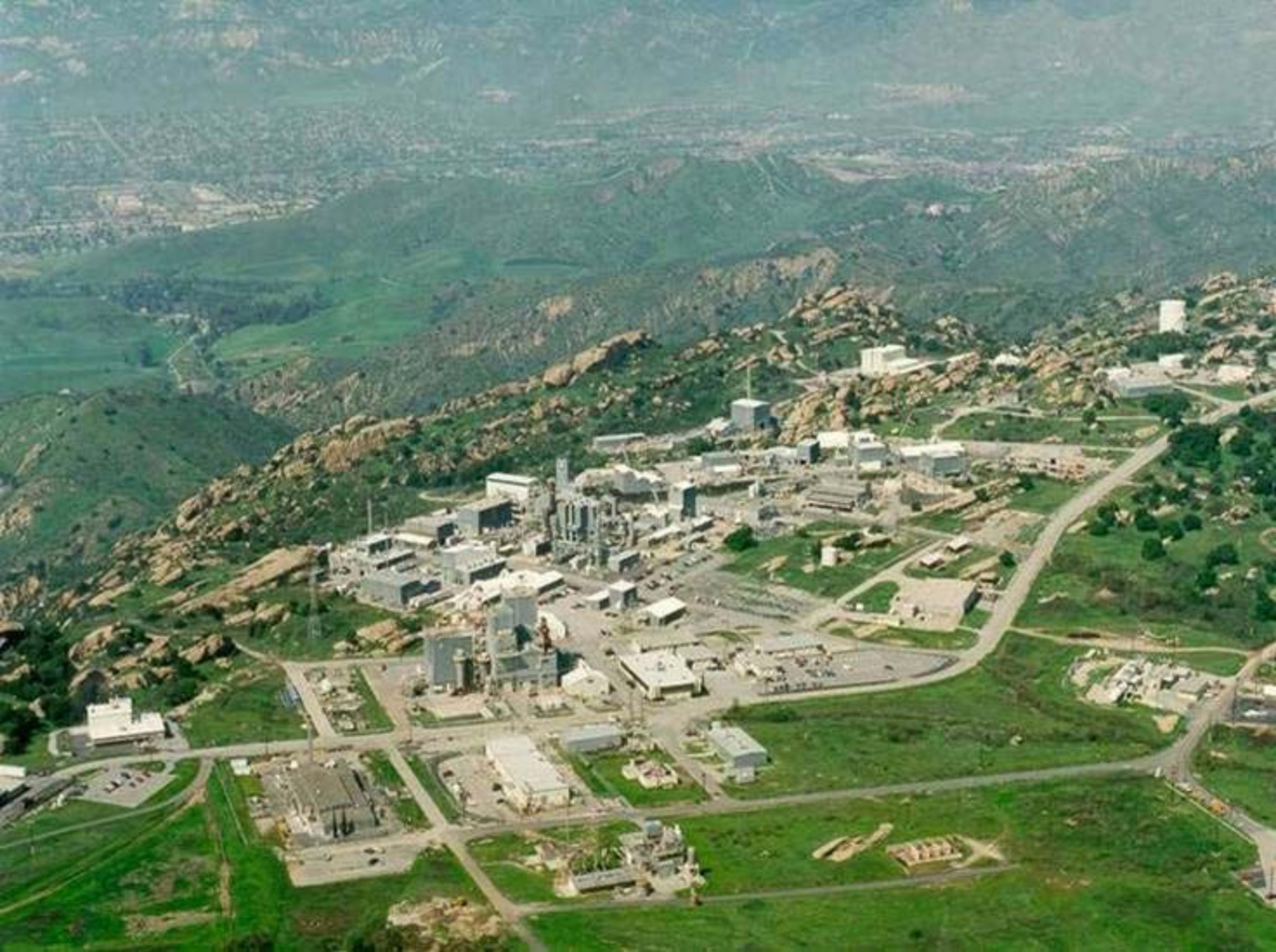

An aerial view of the nuclear section of the Santa Susana Field Laboratory with the small city of Simi Valley visible in the background. [Image credit: U.S. Department of Energy via Wikimedia | public domain]

At 7:30 p.m. on Nov. 12, 1957, the small town of Moorpark, California, lit up with electricity. Turning on the lights isn’t usually a momentous occasion — but in this case, it was. For the first time in American history, private homes were illuminated with electricity generated by the power of the atom.

The suburbs of Los Angeles where I grew up have an unexpectedly rich nuclear history for a residential area. The aerospace company Rocketdyne established the top secret Santa Susana Field Laboratory in the Simi Hills in 1947, putting the sleepy San Fernando Valley on the cutting edge of aerospace research. At that time, the area was sparsely populated, and the location’s proximity to Los Angeles made it ideal as an off-site testing ground for all sorts of new technology, including rocket engines and reactors. The laboratory grew over the years as the Department of Energy, the U.S. Air Force, and NASA added their own facilities to the site. Starting in 1956, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, a predecessor of the Department of Energy, ran many nuclear experiments at the field lab. The commission’s Sodium Reactor Experiment was the plant that powered Moorpark for the first time in 1957.

The field lab also housed radioactive fuel fabrication facilities and the largest hot lab in the country, where technicians remotely cut and tooled nuclear materials too radioactive to handle by hand.

I recently visited the front gate of the Santa Susana Field Laboratory. Some of the buildings can be seen from a nearby, hill-top trail. [Image credit: Preston Tasoff]

But Moorpark did not stay nuclear for long. In July 1959, the reactor had to be manually shut down to prevent overheating after it failed to turn off automatically. An overheated reactor is far more dangerous than an overheated computer because it can melt the radioactive fuel rods. A meltdown can destroy parts of the reactor, allowing radioactive material to escape into the air, water or facility grounds.

And after weeks of problems, that’s what happened. Unknown to the staff at the time, secondary coolant had seeped into the molten sodium used to cool the reactor. It became sticky and clogged the small channels between the fuel rods, causing the reactor to overheat. When workers were finally able to inspect the core, they discovered that 13 of the 43 fuel rods had partially melted. They found 81 pieces of uranium fuel scattered on the bottom of the reactor core, and some rods broke apart later during extraction.

The government buried the event in an inconspicuous press release more than a month after it occurred. The report claims that there was “no release of radioactive materials.” Despite what the press release read, the facility had been venting radioactive gasses into the air for a month and a half before the notice was issued, according to a 2014 presentation at the Santa Susana Field Laboratory Work Group.

Most, but not all, of the radiation stayed in the reactor, absorbed by the molten sodium coolant. But the volatile metal could easily have caught fire or exploded, releasing radioactive ash over what was then the nation’s third largest metropolis. And because the sodium reactor was an experimental, the government didn’t require it to have the familiar thick, concrete containment dome.

The public had no idea anything was amiss for 20 years. After the infamous meltdown at Three Mile Island in 1979, a group of UCLA students decided to see if anything similar had occurred in Southern California. By a stroke of fate, the man who ran the Rocketdyne subsidiary responsible for the field lab had become the dean of UCLA’s engineering school, and had brought boxes of documentation to the school’s library. The students handed all the material over to the local media, who broke the news of the disaster two decades after it had occurred.

I have not detected elevated radiation levels in the hills surrounding the field lab any of the times I’ve brought my Giger counter with me. [Image credit: Preston Tasoff]

The Department of Energy, NASA, and Boeing, the site’s current owners, have been working for over a decade to clean the facility. The location has more than its share of radioactive materials as well as heavy metals, petroleum products, and other chemicals wantonly disposed of in burn pits or allowed to seep into the ground. Contamination has been stabilized, and the community has become officially involved in the clean-up. The lab even hosts public tours periodically as part of the project’s transparency efforts. Someday I hope to make it inside the barbed-wire fence for one of these tours and see the site myself.

1 Comment

I’ve been here a couple times and noticed that life is not up there found pipes sticking out of the ground spewing some type of liquid rusty with rainbow colors on top I would love to do something about this lots of people don’t know about this place