Finding unseen threats to rescue unseen wildlife

An unconventional journey leads a scientist to a new conservation tool: environmental DNA

Jessica Romeo • June 21, 2019

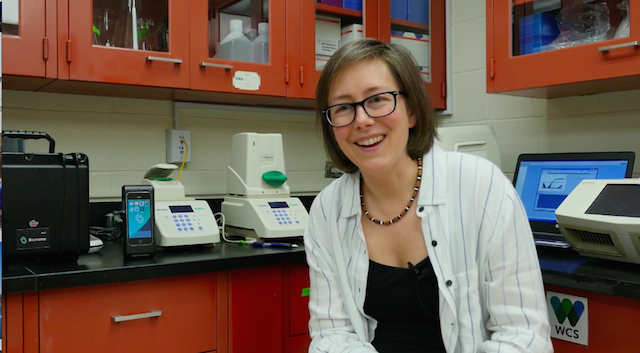

Tracie Seimon's works on the cutting edge of mobile diagnostic technology, around the world and at her home base at the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Bronx Zoo [Credit: Jessica Romeo]

In Vietnam, scientists are using free-floating eDNA, or environmental DNA, found in water samples to scour lakes for signs of the rarest turtle in the world, the Yangtze giant softshell turtle. The only known female died a few weeks ago.

In far east Russia, researchers are using portable eDNA molecular analysis to try to understand the canine distemper virus which threatens tigers and critically endangered Amur leopards. In Rwanda and Uganda, scientists are tracking the spread of the deadly chytrid fungus in local amphibians.

And in New York City, Tracie Seimon stands next to a small turtle pond, scooping murky water into tiny plastic cups. The DNA signature from these water samples will tell her which animal species live in this pond. On the day I met with her, Seimon was expecting to see four different species of pond turtle.

Seimon is a molecular biologist at the Bronx Zoo, which is affiliated with the Wildlife Conservation Society. Her work is being used around the world to protect threatened and endangered animals, including softshell turtles, tigers and frogs.

With her sheepish, easy laugh, Seimon doesn’t let on how impressive her resumé truly is. She does admit, however, that her journey to the Bronx Zoo and eDNA was “not a conventional one.” Initially, she attended graduate school to study experimental pathology.

Tracie’s husband and sometimes-research-partner, atmospheric scientist Anton Seimon, is more straightforward about the magnitude of her career shift. “She was a rising academic in the Columbia Medical School program, in human cardiovascular research, with a very successful career in front of her, getting a lot of recognition, getting great publications,” he says. “And she walked away from that to literally study frogs in the Andes.”

That was in 2010, and Seimon had unofficially been working with frogs for years. Since 2003, throughout grad school and beyond, Tracie has maintained a “side project” studying frogs that live in the high-alpine ecosystems of Peru. When she started, robust populations of all sorts of amphibians were turning up dead. Seimon became one of the first scientists to discover that the chytrid fungus had spread to these local Andean amphibian populations from the lower altitude environments.

Soon after, she started working part-time at the Bronx Zoo, hoping to someday lead her own molecular biology lab.

“Obviously she succeeded and then some,” says her husband Anton. “I think that’s a really laudable and brave thing to do. I think very few people in similar circumstances would have had the wherewithal to make that call and then persevere through it.”

Today Seimon is something of a renaissance biologist, with research projects stretching across five continents. Her central project is the development of mobile genetic identification tools that can be taken into the field to search for rare, hidden species and test for pathogens. “Having these tools simplified to the point where it democratizes molecular technology is really exciting,” she says.

All over the world, from Chile to Cambodia, animals are at risk of extinction from lack of protection and decimating diseases, especially fast-acting fungi. As eDNA becomes more portable and simpler to use, Seimon is happy to share this technology with field researchers all over the world.

“I think the fact that I study a lot of different species and the conservation needs is probably what makes the job so exciting,” she says. “If I was just focused on one thing, I don’t want to say I would get bored, but I love the ability to really spread out and be able to apply these to all the different conservation purposes.”

Oh, and along the way, Tracie also accidentally discovered two new species of high-altitude tarantulas. While she owes that particular discovery to old-fashioned eyeballing, the gears are already turning in Tracie’s head as she sees another potential field application for eDNA.

“We’re hoping we can start to use eDNA in these higher mountain environments,” she says, “so that we can better understand what species are there that we’re not seeing when we’re doing our visual surveys.”