Toxic landscapes: One artist’s life passion

In the midst of a pandemic, an artist and former physicist still works to represent endangered landscapes

Taylor White • September 2, 2020

![Two of Angela Gilmour’s etchings show how natural and man-made events damage landscapes. “Toxic Wednesday” (left) shows what happens when dust clouds from the Saharan desert collide with an Atlantic weather system and pollution. The result is a toxic smog with an orange to red hue that hangs over the United Kingdom. “Blood Rain Thursday” (right) shows the dust and smog released as blood red rain. [Credit: Angela Gimour]](https://scienceline.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Weathertheweather.png)

Two of Angela Gilmour’s etchings show how natural and man-made events damage landscapes. “Toxic Wednesday” (left) shows what happens when dust clouds from the Saharan desert collide with an Atlantic weather system and pollution. The result is a toxic smog with an orange to red hue that hangs over the United Kingdom. “Blood Rain Thursday” (right) shows the dust and smog released as blood red rain. [Credit: Angela Gimour]

“I was always drawing. I was always doing things,” recalls Gilmour. “If there was a puddle, I jumped in it.”

When she was a young girl, Angela Gilmour loved gliding over the whitecaps of the Irish Sea. On trips from her home in Scotland, she would stay glued to the boat’s railing with her head hanging over, watching the waves bend and crash across the bow, thinking about the underlying physical forces guiding them. At her grandparents’ home in Ireland, she would immediately run to the lake, sketchbook in hand, to draw and observe the water and landscapes that engulfed it. She wanted to not only draw nature, but to understand it.

It’s clear that today, the award-winning, engineer-turned-artist does understand the beauty and complexity of nature — her landscape artwork helps others understand too. “The landscape is fragile. It’s receding, it’s retreating, it’s cracking,” says Gilmour. “What we’re looking at now can be something that’s not here in 20 years’ time.”

“Trapped in the pack ice.” Angela’s photo from her trip to the Arctic Circle on the triple-masted sailing ship in June 2019.

When she’s not working at her studio in Cork, Ireland, Gilmour is usually travelling the world and moves with a sense of urgency to depict endangered landscapes before they are gone forever. At the moment, though, she is stuck at home, like hundreds of millions of other people. The coronavirus lockdown has come at an inopportune time for Gilmour, who has been a full-time artist for five years — since leaving her job as a process and product development engineer in the semiconductor industry. Her most recent landscape art was showcased in a “Weather the Weather” exhibition in Queens, New York from September to early March, just before the virus hit. Now, other exhibitions are on hold. Her work is on display at a few spots like the Nano Nagle Place museum, but the lockdown has halted most gallery events. Gilmour’s persistence to make her landscape art, however, has not been slowed by the pandemic. “As a painter, you often work isolated anyway,” she explains.

From her home studio, Gilmour paints picturesque landscape oil paintings depicting barren arctic landscapes — ones she saw when she journeyed on a 18-day expeditionary residency program to the Arctic Circle aboard a triple-masted sailing ship in June 2019. Its decks were full of artists, photographers, writers, scientists and polymaths looking to learn about the Arctic and all the ways it has been damaged by human action.

“Ghost Pier, Pyramiden.” Angela’s oil painting of her trip to the Arctic Circle. It was exhibited at the Backwater Artists Group in Cork, Ireland in November 2019.

The desolation she saw and captured on that trip reminded her of the fragility of nature. “It’s just amazing to watch … It’s also quite frightening to see firsthand the effects,” says Gilmour, “It’s quite sad because it’s disappearing, and everything is stunning.”

Throughout her time at the Cork Institute of Technology’s Crawford College of Art and Design, all Gilmour wanted to do was draw nature and landscapes. But her professors thought her time would be better spent on conceptual art. After all, anyone can do landscapes, they suggested.

“It was always landscapes, and it’s when I went to college they told me to stop doing landscapes,” she laughs.

Gilmour listened to their feedback and opened herself up to other projects. She even became “Student of the Year.” But once art school was over, she went right back to landscapes — albeit ones with far more complexity than she would have created if she hadn’t stepped outside her landscape box and listened to the advice of her teachers.

With her experience as a physicist, engineer, and artist, Gilmour is a jack-of-all-trades when it comes to her landscape art. Using different techniques, she makes sure her art mirrors the interplay of art and science. For some of her work, she manipulates photos she’s taken using a variety of lab-worthy reactions like burning, bubbling, and adding chemicals that react with light. The end result is a photograph that reflects what’s happening in the real world: a “natural” landscape has been burned, bubbled, and reacted with the action of humans.

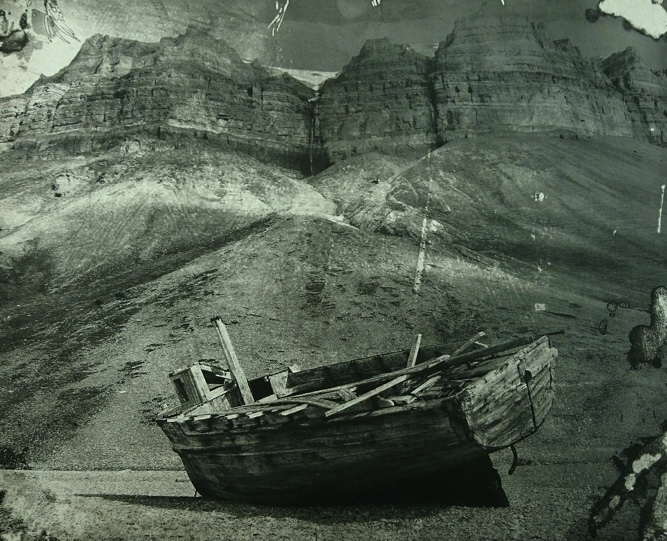

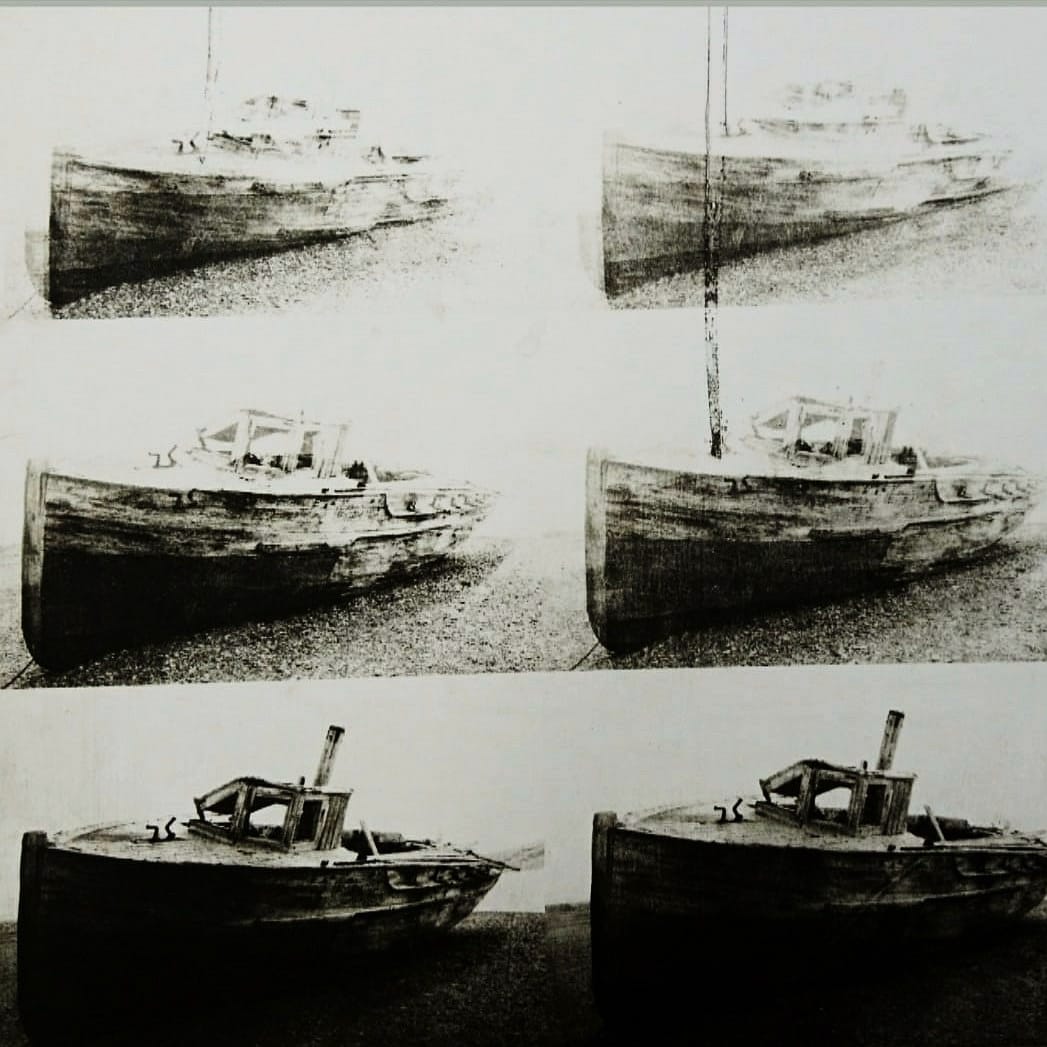

“I combine etching and photogravure, manipulating the process conditions to create an ephemeral, antiquated image suggesting a past that no longer exists, a warning. Often only in the detail are the scars of man or nature’s interventions revealed,” said Gilmour in an email.

“Foreboding Shores.” Angela’s etching of her trip to the Arctic Circle. It was selected for the 139th Royal Ulster Academy of Arts Annual Exhibition in Belfast, Northern Ireland for October 16 2020 through January 3 2021.

Gilmour paints, sketches, etches, and snaps photos of landscapes. These photos, along with her paintings, have been lauded by critics. Gilmour’s etchings and paintings display a “meticulous approach to observation,” says Aideen Quirke, Director of Cork Printmakers in Cork, a fine art printmaking studio where Gilmour produces her work.

“She is using her skills as an artist to communicate what she understands as a scientist. I think it makes her a better artist,” says Quirke. “She’s not obstructing what she sees, she’s not obfuscating anything with artistic license. She is representing what is around her.”

Despite the critical praise, Gilmour remains humble — praise isn’t her goal. Awareness is. During her Arctic journey, Gilmour, along with the other participants, cleaned up trash from the frostbitten land and freezing sea.

“They look like these stunning beautiful landscapes, but when you think about what’s going into the water, a lot of the damage we can’t see,” says Gilmour.

“Untitled xviii, Iceberg series 2019.” Angela’s photo from the Arctic Circle.

One day, while walking across the gravel-covered shore beneath a receding iceberg, the group came across an odd juxtaposition: An old, box-style television set washed up on the bleak shore.

The artwork that results from Gilmour’s observation of landscapes not only clearly depicts reality, but also her personal feelings toward it, says Marnie Benney, a curator for the recent Queens exhibit organized by SciArt Initiative, a nonprofit based in New York that directly supports the creative endeavors of artists and scientists worldwide.

“Her work “Toxic Wednesday, Blood Rain Thursday” is not a happy story,” says Benney, “and those choices — the coloring, choosing etching, and the destruction of the paper — really help push the uncomfortable, destructive narrative behind that instance … The colors are orange and red which is weird, it’s not what normal landscapes look like.”

Even though she likes living green and attracting attention to her art, she doesn’t consider herself an activist. “I’m just an artist that is just interested in the nature and the landscape and it just breaks my heart when I see the pollution,” says Gilmour, “It’s something that I just do personally and if it happens to change somebody’s mind about flinging a plastic bottle into the ocean, then great.”

In June 2021, Gilmour will be showing her new landscape work in Paris at the Escape des femmes art gallery.

“Change the conditions – change the landscape.” Angela’s etching of her trip to the Arctic Circle. This will be exhibited in Paris at the Escape des Femmes gallery in June 2021.