Inside a coastal community’s fight for a greener waterfront

The people of the South Bronx have almost no access to their own coast. South Bronx Unite’s Arif Ullah is working to change that.

Allison Parshall • July 29, 2022

South Bronx Unite’s executive director, Arif Ullah, sees community-stewarded waterfront green space as a way to fight back against the environmental injustice faced by the people of the South Bronx. [Credit: Allison Parshall]

The South Bronx is a community surrounded by water, but walking down the streets and under roaring expressways, you wouldn’t know it.

Down Lincoln Avenue, over the train tracks and through an active construction site sits a small patch of publicly accessible waterfront. Wedged between a waste transfer station and a cluster of luxury high-rise apartment buildings, there is little greenery to be seen at this portion of the Harlem River.

“It’s in a state of ruin right now,” says Arif Ullah, the executive director of the advocacy organization South Bronx Unite. Slabs of cracked pavement and cement barriers dominate the landscape. Erosion eats at the shoreline.

The South Bronx’s waterfront is largely public land, owned by New York State but leased and subleased to a patchwork of private companies like Waste Management, Fresh Direct, and FedEx. Under New York’s Constitution, state land can be leased only for projects in the public good, Ullah points out, but he sees little public good in the polluting facilities along the waterfront.

The Harlem River hugs the southernmost tip of the Bronx, dividing it from northern Manhattan. Over the years, the state of New York has leased much of this public land along the waterfront to private companies. [Credit: Allison Parshall]

At the end of Lincoln Avenue, there is one area meant for the community to enjoy — a pollinator garden planted by Waste Management in 2019 that has since fallen into disrepair. Litter lays nestled in overgrown, straw-colored grass. The small parcel is divided from the road by a cement barrier and hosts a large sign explaining the project. “Our goal is to increase biodiversity and create a space where our neighbors can learn about nature,” the sign reads.

“It’s become a trash receptacle. And I’ve never seen any pollinators around there. Maybe an errant wasp,” Ullah says. “How it could be for the community is perplexing to me.”

A Waste Management spokesperson says the company plans to replant the garden once the nearby construction is completed.

The Waste Management’s pollinator garden at the time of planting in 2019 (left) compared with its state in March 2022 (right). [Credit: Waste Management | Used with permission (left), Allison Parshall (right)]

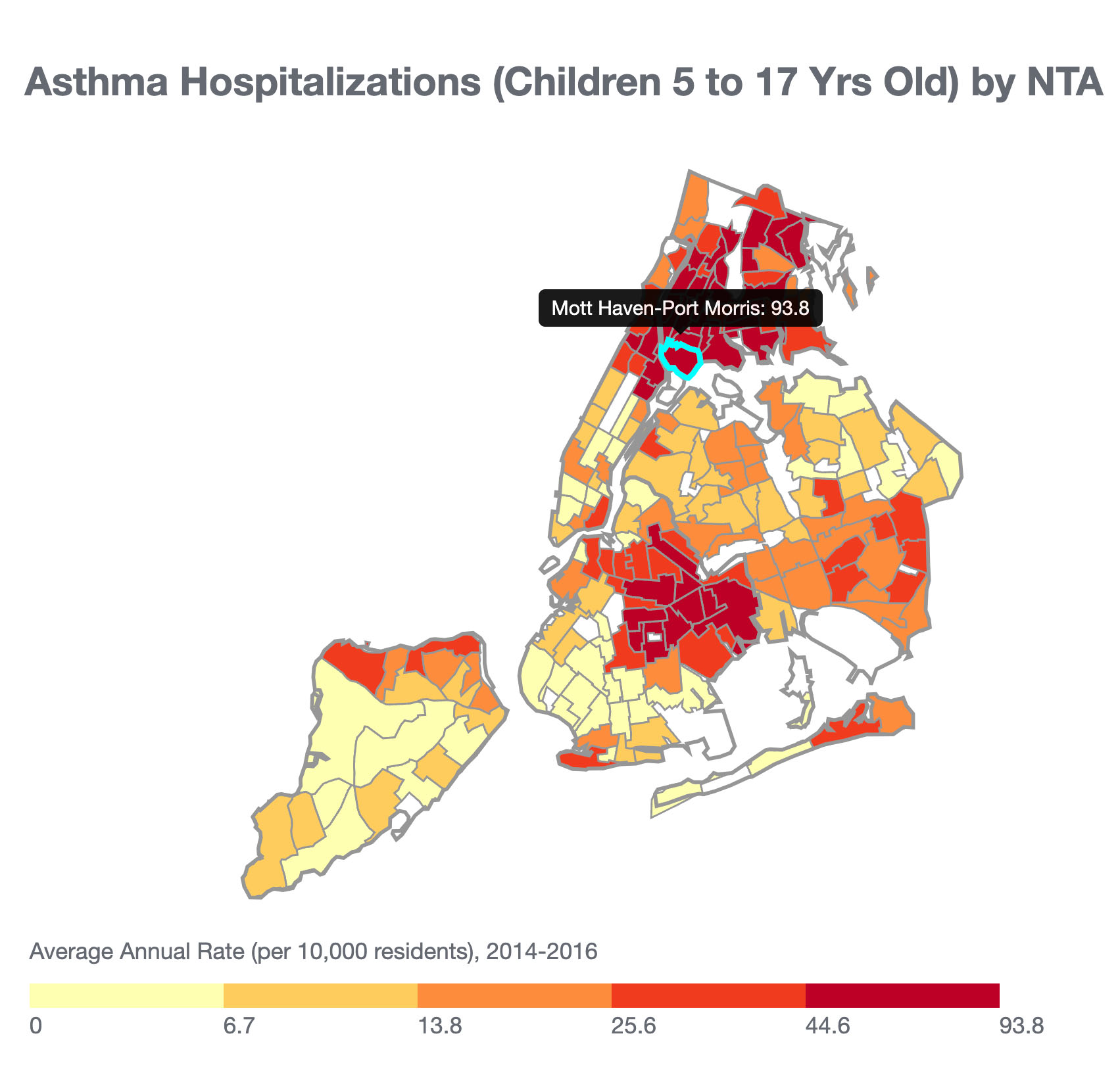

The built landscape of the South Bronx has taken a toll on the community’s health, as well as its landscape. Asthma is a striking example, and one that Ullah knows well. The shoreline neighborhood of Mott Haven has the highest rate of childhood asthma hospitalization in the city, earning it the nickname “asthma alley” — a title it sometimes shares with Astoria, the Queens neighborhood where Ullah was raised. “A lot of my friends growing up had asthma,” Ullah recalls. “Asthma was just a part of life.”

This personal connection is one of many reasons why Ullah was drawn to the work of South Bronx Unite, where he has been the executive director since June 2021. The organization has been campaigning since 2014 to build a series of waterfront parks stewarded by the community. Their Mott Haven-Port Morris Waterfront Plan includes architectural designs for multiple connected sites along the Harlem River. Six years ago, the project was recognized as a regional priority project by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation in their Open Space Plan. But there’s still no clear indication of whether and when any of it will be built — even though other, more affluent parts of the city such as Brooklyn Heights are now enjoying new and much more ambitious waterfront parks funded by a mix of public and private funds.

The Mott Haven-Port Morris Waterfront Plan proposes projects at multiple sites along the water to be connected by a walking path. [Credit: South Bronx Unite | Used with permission]

“We all feel better as human beings being close to water,” says Mychal Johnson, a co-founder and advisory board member of South Bronx Unite who has lived in the area since 2003. Still, many members of the peninsula neighborhood don’t consider themselves a coastal community, he explains. “Some people who live in the community, especially the youth, have no idea there’s water anywhere close in the community,” he says.

Ullah, on the other hand, has always felt a strong connection with nature. Away from South Bronx Unite, he decompresses by meditating and spending time at the Malcolm X Community Garden in Corona, Queens. As one of the garden’s primary stewards, he grows herbs, spices, peppers, and cherry tomatoes — but most importantly, he takes care of the bees. “They’re actually very, very cute,” he says. “They have these beautiful eyes.”

Honey bees keep to their hives in the winter, but when Ullah went to check on his hive at the beginning of spring, he found that his bees didn’t make it through. “It’s always very sad. And it’s not too uncommon of a story for beekeepers here in the city,” he says. He has since picked up three pounds of new bees for his hive.

Ullah, 49, enjoys cooking with the ingredients he grows, but he enjoys his mother’s cooking more. “She’s one of the best cooks in the world. Her love language is food,” Ullah says. His family moved from Dhaka, Bangladesh when he was six years old, and his parents still live in Astoria, where he visits them every week.

Ullah’s low-lying native country of Bangladesh is one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to climate risks according to the recent report of the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. His connection to Bangladesh, along with his love of nature, means that he has always been concerned with issues of environmental justice. In fact, he met Johnson, the South Bronx Unite co-founder, for the first time in Cochabamba, Bolivia, where they were roommates at a conference on climate change. “We connected on a spiritual level immediately,” Ullah says, and they have stayed friends ever since.

Arif Ullah and Mychal Johnson have both lived in New York City for decades, but they happened to meet a continent away. Here they stand on a chilly April day in the South Bronx after a community event put on by South Bronx Unite. [Credit: Allison Parshall]

“It was just a really tight bond,” agrees Johnson. “I always dreamed of working with him.” When South Bronx Unite was looking to take on staff last year, he immediately thought of Ullah, who is currently the organization’s only full-time employee. This year, a decade after its founding, the organization is expanding further by adding three more full-time employees to its staff.

The group’s plan for community-stewarded green space on the water will hopefully address some of the environmental and health inequities built into the community, Ullah says. The highways that cut through the area and the polluting facilities on the waterfront have led to high amounts of air pollution, which is a major factor contributing to the high asthma hospitalization rates, says Matthew Perzanowski, who studies asthma and air pollution at the nearby Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University. In one recent abstract, Perzanowski and his colleagues found that the Bronx accounted for 95% of New York City’s asthma hospitalizations between 2010 and 2016, even though the borough has just 17% of the city’s population.

In the southernmost neighborhoods of the Bronx, Mott Haven and Port Morris, nearly 1% of children ages 5-17 (93.8 out of 10,000) were hospitalized for asthma each year on average from 2014 to 2016 — the highest rate in the city. [Credit: New York City Environment & Health Data Portal]

“All of this has led to toxic air. The air we breathe is killing us,” Ullah says. Beyond asthma, exposure to air pollution has been linked to increased risk for cardiovascular diseases, certain cancers, and dementia.

The lack of tree cover and preponderance of pavement also makes the South Bronx hotter than many other areas of the city, with only one park for about 60,000 people, Johnson estimates. Last summer, South Bronx Unite teamed up with researchers at Columbia and dozens of community participants to measure temperatures across the Bronx and northern Manhattan. The results showed a 7.5 degree Fahrenheit average difference between the hottest and coolest areas surveyed that day. Some of the hottest areas were along the Mott Haven-Port Morris waterfront. The coolest were green spaces and the Upper West Side.

The extreme heat and stagnant air can also exacerbate the impact of air pollution and act as a trigger for asthma attacks. “So it’s critical that we are able to have more green space in our community,” Ullah continues, adding, “It’s not just about recreation, it’s about our health.”

Six years have passed since the Mott Haven-Port Morris waterfront plan first received priority recognition from the state, but without the political will or private money necessary to push the project forward, little progress had been made, Johnson and Ullah explain. Meanwhile, other waterfront projects across Manhattan and Brooklyn have been completed, like Little Island, which opened in 2021, and Brooklyn Bridge Park, which has unveiled new sections of parkland almost every year since 2010.

Brendan Pillar, deputy director of the New York City Department of City Planning’s waterfront division, points to the multiple city and state jurisdictions along the Harlem River as an ongoing challenge for developing the waterfront. While most of the land is state-owned, the plan will require cooperation of many state and city departments, as well as action by local elected officials and stakeholders. The current industrial uses of the land may also present safety concerns in specific areas along the waterfront, he says.

Waterfront parks have been built all over the city in the past decade, like Little Island in Chelsea (left), and Brooklyn Bridge Park in Dumbo (right) [Credit: Jim Henderson via Wikimedia Commons (left), Allison Parshall (right) | CC BY 4.0]

But Ullah feels a new momentum behind the South Bronx waterfront project thanks to the spotlight placed on Black and brown frontline communities by the Black Lives Matter movement, he says. In April, South Bronx Unite gave a tour of the waterfront to the commissioner of the state Department of Environmental Conservation, Basil Seggos, thanks to a serendipitous community connection. “It’s not every day that a small community group like ours gets to speak directly with the DEC Commissioner,” Ullah says.

South Bronx Unite also has the backing of other community land organizations, within their own community and across the city. At a community event in April, advocacy groups like the Waterfront Alliance, Nos Quedamos, and the Western Queens Community Land Trust came out to show their support for South Bronx Unite’s plans for the waterfront and a future community center.

“Arif [Ullah] and South Bronx Unite are just doing a tremendous job drawing attention to these issues, mobilizing and organizing,” says Karen Imas, the vice president of programs at Waterfront Alliance, a non-profit that advocates for equitable waterfront access across the city and is now working with South Bronx Unite to build out the Mott Haven-Port Morris plan. “I’ve learned a lot from working with them,” Imas says.

Ullah and his colleagues at South Bronx Unite aspire to a future where the South Bronx is known for green space, community centers, well-performing schools, and innovation. He sees past the concrete and weeds to the waterfront park that may one day help filter the air, provide relief from the heat, and give the South Bronx community access to the rivers that have always surrounded them. “And that’s all within the realm of possibility,” he says.

(Subway noise) (Car horns and street noise) Arif Ullah: We’re a coastal community here in Mott Haven and Port Morris, yet we have zero access to our waterfront. There are no access points to our waterfront. That’s unjustifiable considering that so many other parts of the city have access to their waterfront. We’re going through a waterfront renaissance here in New York City. I can point to several parks that are on the waterfront in Manhattan and in Brooklyn. Our section of the waterfront is public land, but it’s leased by a for-profit private company. They sublease that land and are generating a handsome profit with public land. So, several years ago, we started a campaign to get access to our waterfront. It is a state-prioritized waterfront plan. It would finally, if we’re able to get access to the spaces that we need, it would give us an open air waterfront park. We are in Brook Park community garden, which is just such a beautiful community gathering space, a safe space. And these types of spaces, unfortunately, in our community are very limited. Not surprisingly, the South Bronx is hotter than many other parts of the city, most of the parts of the city. And that’s definitely because of the landscape of our community. The impermeable surfaces, the lack of open green space. The “parks” that have been built in recent years, they’re all asphalt. So our waterfront plan is part of the land trust initiative. Community land trusts build public benefits using public space. A lot are focused on housing. We think that public land should also be used for other public benefits, including, for example, open green space. Arif Ullah (speaking at event): We talk about the public interest. Public land in public hands, come on y’all. Audience and Ullah: Public land in public hands! Arif Ullah (speaking at event): That’s what we’re about. Arif Ullah: So the waterfront, one section of it, is all of the polluting facilities. And then in another section, we have seven luxury high rises going up. I can’t imagine what rent will be in these units. And that’s going to also change the character of the neighborhood. So it’s not just about housing becoming unaffordable, it becomes about stores, restaurants in the area becoming unaffordable for the people who live here. The South Bronx is a community that has, when depicted in the media, been depicted in a negative way. You know, there’s so much culture and beauty in this community. The South Bronx gave us hip hop and bomba. We’re so rich in culture. We want to make it so that when people think about the South Bronx, they think about green space, they think about community centers. If we’re given the resources that we need to be able to do that, we can thrive. (Birds chirping) (Car horns and street noise)

1 Comment

Inside a coastal community’s fight for a greener waterfront explores how local residents are working together to protect their shoreline through sustainable practices and environmental conservation efforts.