Why so many of us love Taylor Swift

Our love of celebrities can be explained by psychology — but be careful not to go overboard

Kohava Mendelsohn • February 5, 2024

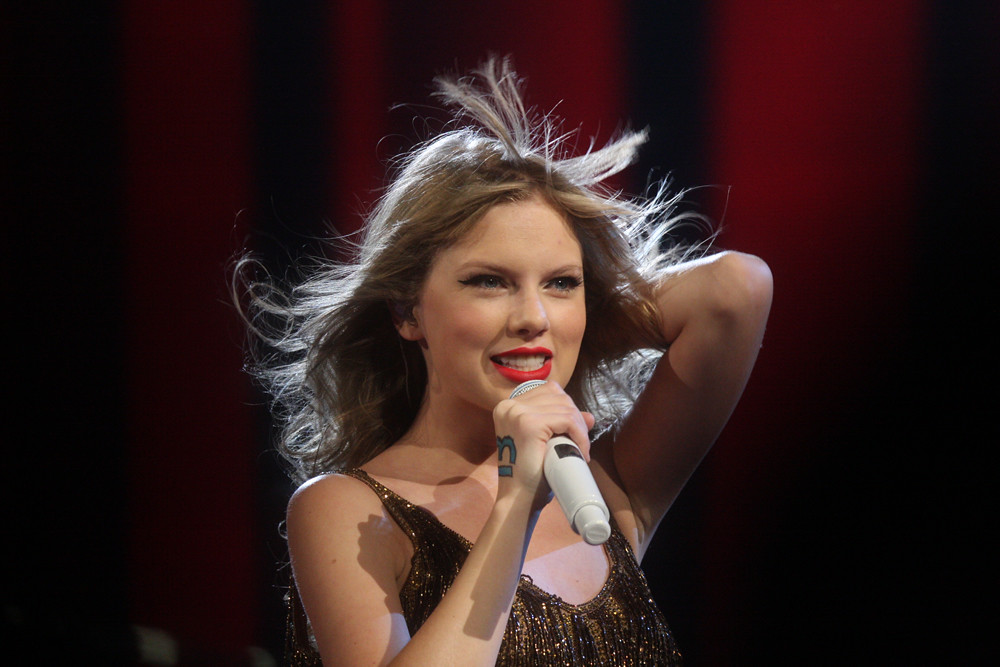

Our desire to be close to celebrities can be just as strong as our desire to be close to friends and family [Credit: Eva Rinaldi | Flickr]

You’ve streamed thousands of hours of her music. You coordinate your outfits to look like hers. You flew across the country to see the Eras tour — five times. You’re even watching the NFL now in case she’s at the game. But have you ever wondered why you’re a Swiftie?

Psychologists have. They have developed scientifically supported theories about why celebrities are so attractive to the rest of us, and why it can be dangerous when our parasocial relationships —when you imagine you’re friends with someone who doesn’t know you— shift from fun diversions to unhealthy obsessions.

Celebrities, of course, want to encourage these one-way relationships to generate more fans and income, and the dominance of social media has made it easier than ever to create spaces for fandom. Today, whether or not you have a busy social life, almost everyone has a busy parasocial life.

So, what can psychologists tell us about our relationships with celebrities?

“We are wired to connect to other people,” explains Lynn Zubernis, a psychologist at West Chester University in Pennsylvania who has written eight books about the psychology of fandom. “That’s the way humans have stayed alive for a long time,” she says. Talking to people helped our ancestors learn new information and pass it on through generations. The best socializers lived longer and safer lives, passing their genes on to more children. We became a social species.

This need for connection is a key reason why we have friends, and also why we’re so connected with celebrities. “We form attachments to celebrities — even though we don’t actually know them — because our brains are not really very good at telling the difference between someone who is in our home every day and someone who is on our screen every day,” Zubernis says. Someone on a screen can be in our lives just as regularly as a friend, so our brains can have the same reaction.

We see celebrities everywhere, so it would be strange if we did not develop bonds with them in light of their “ubiquitous and glamorous presence,” says Dara Greenwood, who studies psychology and media at Vassar College in New York.

Once we feel emotionally close to celebrities, we then want to be physically close to them — a behavior Zubernis calls “proximity seeking,” which is also part of our evolutionary history. “Babies needed to be near to their caregivers, or they were going to be eaten,” Zubernis explains. “That’s why people pay a lot of money to go to a Taylor Swift concert. They want to be in the front.” They want Taylor Swift to look at them, “because that’s what we want from our attachment figures,” she says.

Not only do our brains place celebrities in the same category as friends, but they also become role models for us. This, too, has its roots in evolutionary biology: It was helpful for our ancestors to be connected to the people in charge and emulate them.

“We always look for exemplars. We look for people to look up to, to be role models,” says Zubernis. Celebrities provide an example of how we can become successful in society, and they can help younger people figure out who they want to be by defining themselves as part of a group of fans.

There are other benefits, too — including the simple pleasure of having fun. “Celebrities enable us to feel joy or amusement, motivate us to be empathic and prosocial, to overcome adversity or to reflect on our lives more deeply,” Greenwood says.

Zubernis’s research has found that fans tend to have higher self-esteem, more happy experiences and less stress. She says that’s because our brains benefit from social connection, either with celebrities or with other fans. Fan communities, she adds, bring us a sense of belonging and a safe space — all traits that evolution encourages. In prehistoric times, she explains, “if you didn’t belong to a group, you were probably dead.”

But of course, celebrity obsession can go too far. Celebrity Worship Syndrome is a psychological disorder that represents the extreme end of being obsessed with a famous person. For most people, fandom is not a concerning issue. But for a relative few, it can be dangerous. “If someone is so obsessed with Taylor Swift that they need to go to every concert, but that means they can’t pay their mortgage or feed their children,” Zubernis says, “then we’ve slipped into something that is clearly bad for you.”

There’s another potential downside too: being a superfan can create unrealistic or unhealthy goals of success, leading us to value certain qualities or identities — being white, young or thin, for example — above others, Greenwood notes.

Parasocial relationships are becoming more intense and ubiquitous with the rise of social media, says Weylin Sternglanz, a professor of psychology at Nova Southeastern University in Florida.

This “illusion of friendship” is strengthened in the digital era, Sternglanz says. Now celebrities can respond to people on social media, interact with live streams and appear on phones as often as fans want. “The size of [celebrities’] potential audience has never been so vast,” Greenwood says, which means “the potential impact of any one person has never been quite so powerful.”

So go ahead and spring for those front-row Taylor Swift tickets if you want to, just keep a close eye on your bank balance. The message from scientists who study the psychology of celebrity is clear: take joy and find meaning in all the positive aspects of fandom, identify people who share your interests and form communities with them. But don’t forget that celebrities are financially motivated to get you engaged, and be careful not to lose yourself in a one-way relationship.