Televised Debates: Insert Audience Response Here

The motivation for audiences to participate in presidential debates is more than just party fever

Leslie Nemo • January 16, 2017

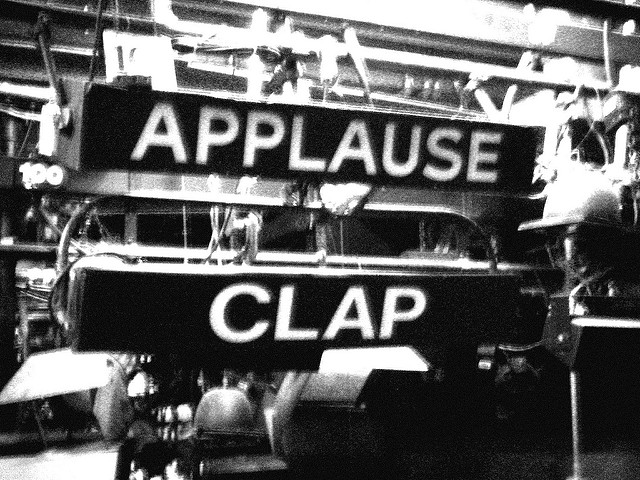

There are no signs demanding debate audiences to participate, so what prompts them to cheer and jeer when they’re supposed to be silent? [Image credit: flickr user Emily Tan, CC BY 2.0]

Like a parent begging children to clean their room, Frank J. Fahrenkopf Jr. pleaded with the live audience at the first general election debate between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton — “Please, keep quiet.”

The televised event is not just for you, explained Fharenkopf, the co-chair of the Commission on Presidential Debates, but for people at home as well. His requests were enthusiastically ignored. At nine different instances in the 90-minute debate, the audience put their hands together, even after the moderator stopped discussion to remind them all of their promise to stay quiet.

Rebellious audiences in presidential debates are nothing new. Research has found competitive natures and gut reactions spur crowd participation — and also that the behavior influences other viewers. It’s possible the source of the problem isn’t in the audience, however, but in the very candidates they’re rooting for.

To be sure, audiences can hardly resist playing an active role. At a basic level, audiences break promises to moderators because debates are ultimately a competition.

Steven Clayman, a sociologist specializing in presidential behavior at the University of California Los Angeles, puts what motivates an audience to respond into perspective. Say you’re a Democrat, he says, and the Republican candidate has a particularly good line that gets their supporters riled up. “That’s going to crank up [your] incentive to respond,” he says. If you don’t show your disapproval with the Republican’s comment, “people might walk away with the mistaken impression that whatever was said has the full support of everyone in the room.”

Retaliation responses played out in a 1993 study by Clayman, in which he tracked audience responses during the 1988 George Herbert Bush-Michael Dukakis debates. When candidate Bush, who ultimately became the 41st president, delivered pointed lines and received applause and cheers, it only took a few seconds for hissing and booing to surface from elsewhere in the audience.

This feedback is heard by viewers at home and influences their opinions. Steven Fein, a psychologist at Williams College, invited undergraduate students to watch one of the live Bill Clinton-George W. Bush ‘92 debates on campus — Clinton was the nation’s 42nd president and the winner of this debate, while G.W. Bush was our 43rd president. The students were split into one of three classrooms – one with study confidants who booed and cheered to support Clinton, one with confidants who actively supported Bush, and one without any study insiders.

Students scored the candidates on their performances afterwards. The room without insiders saw Clinton outperforming Bush by an average of 23 points, a decisive victory in line with what expert analyses of the debate concluded. In the pro-Clinton room, however, he scored 51 points higher than Bush. And while Clinton still had the lead in the pro-Bush room, it was only by six points.

Even though he and his fellow researchers knew about the planted conspirators, said Fein, they all left their respective rooms convinced of different outcomes of the debate. “That’s how we knew this worked, even before looking at the data,” he says.

If audience responses are so influential, then there must be a way to curtail them. Clayman has a couple ideas. To deal with clapping and booing, Clayman suggests forcing audiences to integrate. In the ’88 election he studied, Republicans and Democrats were split, each sitting in front of their candidate. A divided audience “is an interesting ecological situation,” Clayman says. “Everyone knows that everyone around them agrees with them.”

Humans are more comfortable expressing opinions if they think others side with them, Clayman explains. “We don’t like to go out on a limb if we can avoid it.” Maybe by forcing people to sit around others who may or may not feel the same as they do, audiences would feel uncomfortable starting the first couple claps or boos.

While jeering and applause require some degree of forethought, laughter does not. If an audience really isn’t supposed to clap, “people can sit on their hands,” says Patrick Stewart, a political science researcher at the University of Arkansas specializing in audience behavior, “but laughter is automatic and contagious.”

Candidates want to make their attendees chuckle, says Lawrency Levy, an experienced political reporter who has also moderated a few congressional debates. “Being able to make somebody laugh is in the same ballpark as making voters feel you’re someone they wouldn’t mind having a cup of coffee or a beer with,” he says.

Stewart put numbers to this behavioral observation after tallying and timing the outbursts of laughter during the Republican primary debates of 2012. Each debate that year had such different levels of audience encouragement from moderators that a candidate threatened to drop out.

The duration of individual instances of laughter at each debate varied, but the number of times the crowd laughed didn’t, according to Stewart’s study. No matter the moderator’s requests, audience members could only tame their outbursts once they happened, not find fewer comments funny.

And while the evidence shows it’s much harder to keep audience members from laughing, Stewart thinks there could be something done to keep laughter from spreading. Debate venues could put space between audience members and be acoustically designed so initial chuckles don’t echo and prompt more.

Neither Clayman’s or Stewart’s ideas for audience management have yet been put to the test. And maybe they don’t need to be. “The tougher task is to control the candidates, not the crowd,” says Levy. To him, stopping audience laughter is impossible if politicians continue to deliver lines explicitly crafted to elicit emotion.

Incorporating one-liners has been an obsession in presidential debates since the 1980 campaign, says Kathryn Brownell, a historian of the American presidency at Purdue University. An example from this election, Brownell offers, was this year’s Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton’s “Trumped up, trickle down” line. Each candidate goes through “a lot of rehearsals to present [their] message and the one-liners they hope will stick and dominate the post-debate narrative,” she says.

And dominate they do. “You’re not going to get a two-minute discussion of policy that’s on the news,” adds Fein. Since the media focuses on zingers, candidates are willing to put effort into memorizing and performing packaged lines.

In his time as a debate moderator, Levy says, the best way to address potential one-liners and audience feedback is to tell the candidates themselves — “Public displays of affection are not going to be part of this.”