Coral reefs may succumb to erosion on a warmer planet

Researchers project that coral reefs will not keep up with rising sea levels, reducing their ability to protect coast lines

Emma Smith • December 1, 2025

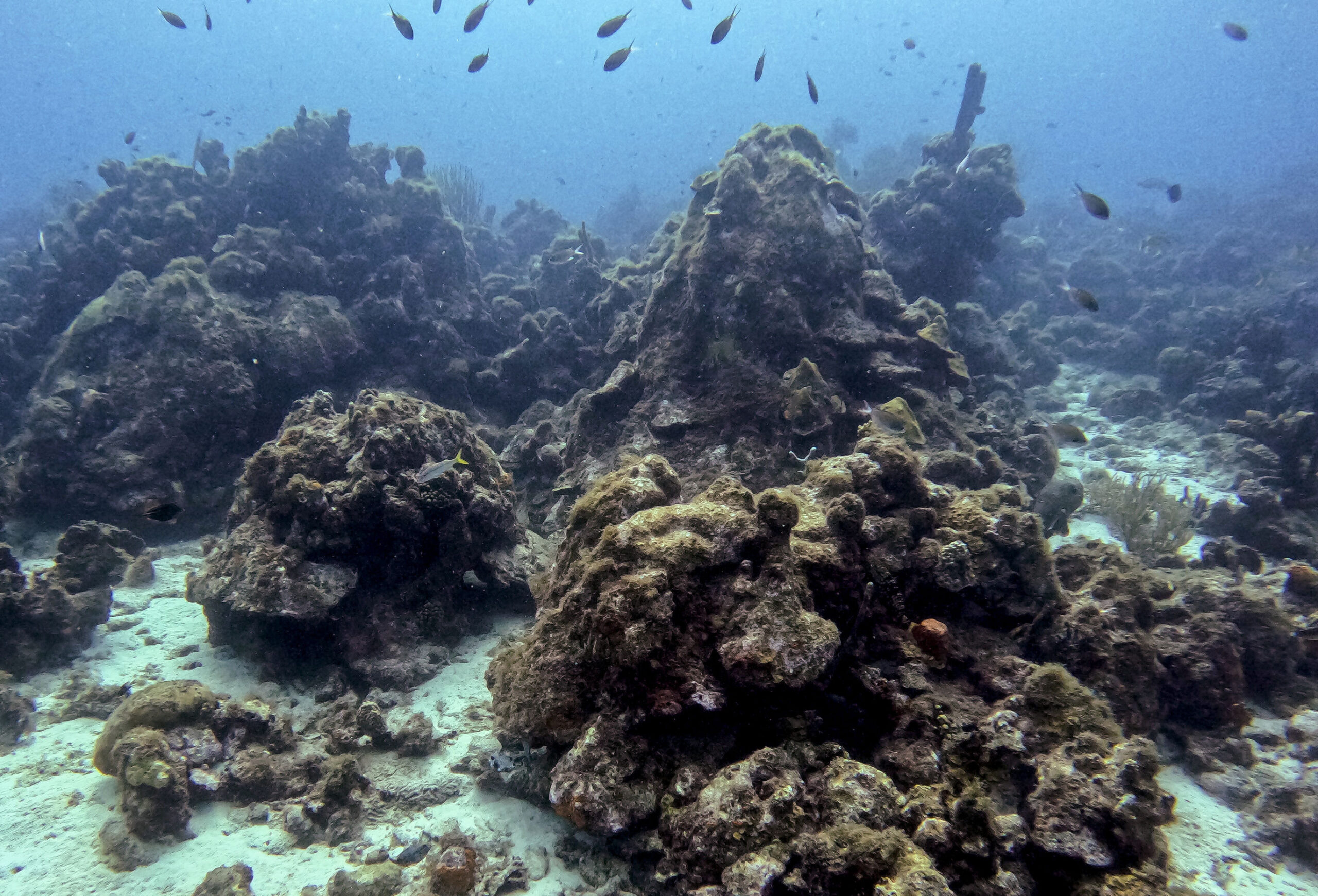

The remnant skeletons of a Caribbean reef in Bonaire where almost all the coral has died due to a combination of heat stress, disease and declining water quality. This structure will slowly erode and flatten over time. [Image Credit: Didier De Bakker]

Coral reefs are under stress. Oceans are the largest absorber of carbon, and accelerating emissions are leading to increasing ocean temperatures, acidification and rising sea levels.

Coral may be in imminent danger, warned a study reported in Nature this September. According to the report, the majority of coral reefs in the Western Atlantic may not be able to keep up with rising sea levels and will succumb to erosion if global warming reaches 2 degrees Celsius, as is expected by 2050.

To understand the impacts, researchers at the University of Exeter in the U.K. gathered eight years of data from over 400 reefs throughout the Western Atlantic, focusing on sites where data is most prevalent. In the Florida Keys, the Gulf of Mexico and Bonaire in the Caribbean, they examined the rates at which coral reefs are growing and eroding, known as reef accretion potential (RAP), to project what may happen as a result of rising temperatures.

In the study, researchers were able to provide a more detailed analysis of projected RAP for these reefs by incorporating different estimates of the coral’s reef porosity — the proportion of empty space within the reef framework, which varies across sites.

They estimated that by 2040, more than 70% of reefs may enter a state of “net erosion,” meaning they will erode faster than they can grow. The trouble will arise from both warmer ocean water and higher sea levels, which the researchers estimate may increase by roughly 10 to 25 centimeters (3.9 to 9.8 inches) above present levels, depending on location and emissions scenario.

“If we don’t do anything on a global scale in terms of [carbon dioxide] mitigation, this is going to continue,” said Didier De Bakker, a co-author on the paper and reef ecologist, who studies Caribbean reefs and how they are maintaining their ability to grow despite shifts in carbon in the atmosphere. “These periods of prolonged high sea surface temperature, they’re going to become longer and longer. It’s going to therefore be harder and harder for any coral species…to deal with it and to survive.”

Researchers said this will likely impact humans, too. Coral reefs systems work as a makeshift traffic controller, using their complex, physical structure to flash the equivalent of a yellow light, creating friction and slowing down waves as they move through reefs. Reefs reduce wave energy, a measure of their ability to cause damage along the shoreline, by 97%, which helps to protect coastlines. Rising sea levels already cause an increase in water depth above reefs, which will further impact their ability to buffer wave energy along coastlines, leading to more erosion and flooding.

Corals are sensitive to water temperature changes and often do best between 73 and 84 degrees Fahrenheit (23 and 29 degrees Celsius), depending on their species. As oceans absorb more carbon, creating a warmer and more acidic environment, calcium carbonate — a key ingredient for coral’s skeletons — becomes less available, hindering coral’s ability to grow. This combined stress and rising water temperatures pushes corals to expel algae and turn white, a process known as bleaching, leaving them more susceptible to disease and erosion. And this is happening in reefs across the world.

“The type of bleaching we’re talking about is bad for corals in all scenarios,” said John Parkinson, a reef ecologist and professor at the University of South Florida. Parkinson was not involved in the new study. “It’s a stress response, like a fever, and indicates the coral is experiencing damaging conditions.”

Coral bleaching happens often in the Florida Keys, where reefs are not in good health, according to the British paper.

Parkinson was working on restoration efforts when an unprecedented marine heat wave rolled through. “The big marine heat wave of 2023 came through the Florida Keys … [and] a lot of the natural corals of the species that we’re interested in unfortunately died,” Parkinson said.

During the heat wave in the Florida Keys, temperatures reached 90 to 101.1 degrees Fahrenheit (32.2 to 38.4 degrees Celsius), well above the average of 84 degrees. For comparison, the temperature of a hot tub is between 100 and 102 degrees (38.3 to 38.9 degrees Celsius).

Parkinson has been diving in the Florida Keys since 2007 and said that coral reefs look different today. However, he doesn’t think that coral reefs will be gone on a warmer planet. “They will be different. They won’t be as diverse, they won’t be as big and they won’t be providing the same ecological goods and services to humans or other organisms as they used to.”

1 Comment

Rising sea levels and acidification pose significant threats to coral reefs, as highlighted in the study reported in Nature. Will researchers explore solutions to mitigate these effects and protect coastlines, or is it a lost cause for these vital ecosystems?