Should national labs reinvent themselves?

American science needs the U.S. national laboratories, but the system could use an update

Rebecca Harrington • June 10, 2015

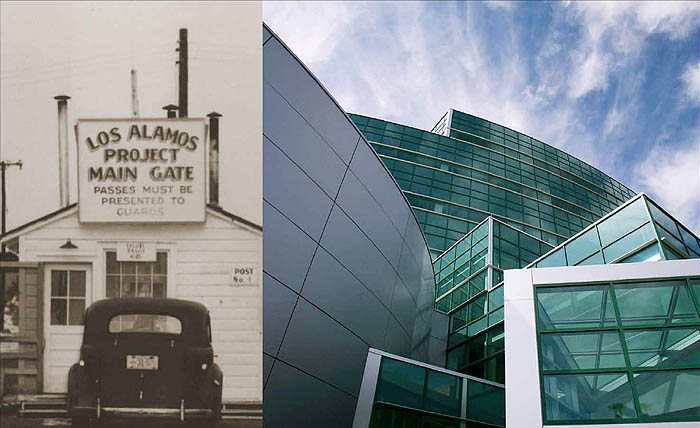

Then (1940s) and now at Los Alamos National Laboratory. [Image credit: Los Alamos National Laboratory]

Like a lot of Americans, I vaguely knew of Los Alamos and Oak Ridge national labs, mostly because of their involvement with the atomic bomb and national security. But it wasn’t until I worked in the communications office of Brookhaven National Laboratory last summer that I realized there was a whole system of them.

The U.S. national laboratory system employs 22,000 people at 17 labs across the country. These sprawling complexes — the backbone of basic science in the U.S. — cost their parent company the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) more than $11.2 billion in fiscal year 2015. The labs have come a long way from their origins propelling the allies to win World War II. Each lab resembles a small city, occupying acres of land, many with their own fire departments, post offices and zip codes. Basic research, from high energy physics to molecular biology, is core to the labs’ missions, which can make its immediate practicality difficult to justify to society, said Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory Director Nigel Lockyer. “We’re asking questions about the beginning of the universe. Sorry, that’s what we do,” he said. “So we’re trying to hang on to that, and we’re very proud of it. And we’re trying to tell people it has value.”

But are the labs still well equipped to do the best science? Critics, among them DOE auditors and congressional leaders, in recent years have called to shrink, consolidate or refocus the national labs. After living at a national lab for a summer, I became skeptical, too.

The labs weren’t always this big. They began as a way for the brightest scientists of the 20th Century — Albert Einstein, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Enrico Fermi and others — to come together in the national effort to win World War II. Their crowning and devastating achievement was the atomic bomb. After the war, the federal government made the labs permanent so they could continue to solve big scientific questions the nation needed to answer, with each lab’s research focused around its own big machine or pursuit, from particle accelerators such as Fermilab’s Tevatron to nuclear science at Los Alamos. Though the national lab system has evolved, inefficient relics remain from its long history.

Some of the labs were created with identical missions in the aim of competition and hopefully better science. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory opened in 1952 with the same mission as Los Alamos — nuclear science. DOE money only pays for the staffing and operational costs of running the lab and its big machines, so researchers have to compete for additional grants to fund their individual work. The idea was to use this grant money to weed out projects that were too similar since only the best research would (theoretically) win the funding. But the labs are inescapably duplicative, in both their research focus and their administrative overhead, the DOE Inspector General found in a 2011 audit. The audit report recommended eliminating any overlap, which seems like it could be a cost-saving solution.

In an era of flat government support for research, eliminating excessive spending is crucial. The report also found that support costs such as non-science staff, day-to-day operations and executive oversight made up 40 percent, which amounted to $3.5 billion of the national lab budget in fiscal year 2009. “We concluded that this cost structure, specifically the proportion of scarce science resources diverted to administrative, overhead, and indirect costs for each laboratory, may be unsustainable in the current budget environment,” DOE Inspector General Gregory Friedman said in the report. This bloat was apparent to me in the summer I spent at Brookhaven. The DOE required so much paperwork for every little thing anyone did — from running an experiment in the particle accelerator to changing a lightbulb — that I saw time and money spent on administrative tasks which could have been devoted to science instead.

Procedures to ensure safety are obviously warranted. National labs conduct security work that must be protected and run potentially dangerous experiments (with radioactive materials or infectious agents, for example) that must be contained. The DOE needs to ensure proper oversight of the network, but at what cost? If the agency cut down on the amount of paper and administrative work it required, it could allocate a lot more time and money to actual science.

And the country needs that money to fund the kind of big science that researchers can only conduct at national labs — big machines such as the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider at Brookhaven, where researchers smash atoms together to determine how the universe formed, or the Trinity supercomputer at Los Alamos, where scientists simulate explosions without having to detonate any bombs. When U.S State Department officials were negotiating the nuclear treaty with Iran, they turned to Oak Ridge to find out how long it would take to enrich uranium intended for energy or medical applications into a bomb-ready substance. The lab even built a replica of Iran’s nuclear facilities, according to an April article from The New York Times. Other labs, including Los Alamos, double-checked Oak Ridge’s equations — an instance in which the built-in competition was actually an advantage.

Private companies won’t spend enough money on basic research because they have to make profitable products and satisfy stockholders. Universities support some basic research, but their projects don’t reach the scale that national labs can. Therefore it’s up to the federal government to fund big science that teaches us the fundamentals of the world around us.

![An aerial view of Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, where in September 2011 the lab had to shut down the Tevatron particle accelerator, which at one time was the most powerful in the world. [Image credit: Flickr user Fermilab Communication]](https://scienceline.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/5436459448_1f53fa11fb_o-1-640x480.jpg)

An aerial view of Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, where in September 2011 the lab had to shut down the Tevatron particle accelerator, which at one time was the most powerful in the world. [Image credit: Flickr user Fermilab Communication]

Fermilab and the particle physics community have decided what the next frontier will be: neutrinos, the tiny subatomic particles that could be the missing mass of the universe. Physicists theorize neutrinos could help explain how the universe consists mostly of matter rather than antimatter. So Fermilab plans to build the world’s most powerful neutrino beam. Construction, slated to begin in fall 2016, will create the massive detector a mile underground, and Lockyer said the machine will be ready for experiments by 2028. But the lab has to secure approval and funding from the DOE and international partners first.

Fermilab is turning to the international community to help design, build and fund its Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, which will cost an estimated $850 million, because Lockyer said no single country can pay for big science like this anymore. “Funding is going to be extremely difficult,” he said. “It’s just the way the world is now. It’s not just the U.S., it’s Europe, it’s everything. That’s why we’re going international.”

In a way, this shift to more international science brings the national labs back to their roots, when emigrant scientists from Germany, Austria and Italy worked side-by-side with Americans on the Manhattan Project. Most big science, especially basic research, should be done at the international level. Operating across borders allows the best minds to come together on questions, from clean energy to nuclear security.

Tevatron and Fermilab’s ongoing evolution are indicative of how the national labs have had to reposition themselves over the years, and this need for reinvention will never end. Los Alamos had to diversify itself for the first time when nuclear weapons tests fell out of public favor and Russia proposed a moratorium in the 1950s. The lab’s official historian, Alan B. Carr, said Los Alamos started branching out to study thermonuclear energy and nuclear verification technology — research related to nuclear weapons, but no longer all about bombs. And that evolution still continues today. “The labs don’t just work for themselves. They respond to national needs. I think that will continue to play a huge part,” Carr said. “What does the nation need? What will make the nation a better place? That has driven our lab [and others] more than anything else.”

So what does this changing landscape mean for the future of the national lab system? It’s large and often inefficient, but so is the rest of government. The system should shave down its bureaucratic red tape, its costly administrative overhead and its duplicative research and personnel functions, and refocus on what the nation truly needs. The national labs will always be essential to American science. They just need a pruning.

*Correction, June 12, 2015:

A previous version of this story used the old name of Fermilab’s neutrino experiment. It is now called the “Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment.” The top image caption also incorrectly identified the location of the first detonation site of the atomic bomb. It was at the Trinity bomb site in New Mexico.

3 Comments

Agree! The national labs should work to address more national problems within limited budgets. Only in this way it won’t be a waste of the investment put in when they were established.

The caption on the first set of pictures is wrong. “Then (1940s) and now at Los Alamos National Laboratory, the first detonation site of the atomic bomb.” The first detonation of an atomic bomb actually occurred at Trinity Site, located on what is now known as the White Sands Missile Range. Trinity Site is in the southern part of New Mexico. Los Alamos National Laboratory is in the northern part of New Mexico.

This isn’t your typical chsrmetiy curriculum. Each chapter is just a list of questions and students must find the answer for themselves. You also get chapter quizzes and tests. The labs are easy to follow. I like the structure and that my son gets quizzed so I can check if he’s actually learning anything. There’s a teacher manual but you have to buy a textbook or find online resources so your child can find their information.