Fungal infections are killing millions. Why don’t we have more treatment options?

Overtreatment, climate change, travel and farm chemicals are driving resistance to antifungal drugs, and a possible new treatment is likely years away

Marta Hill • January 30, 2025

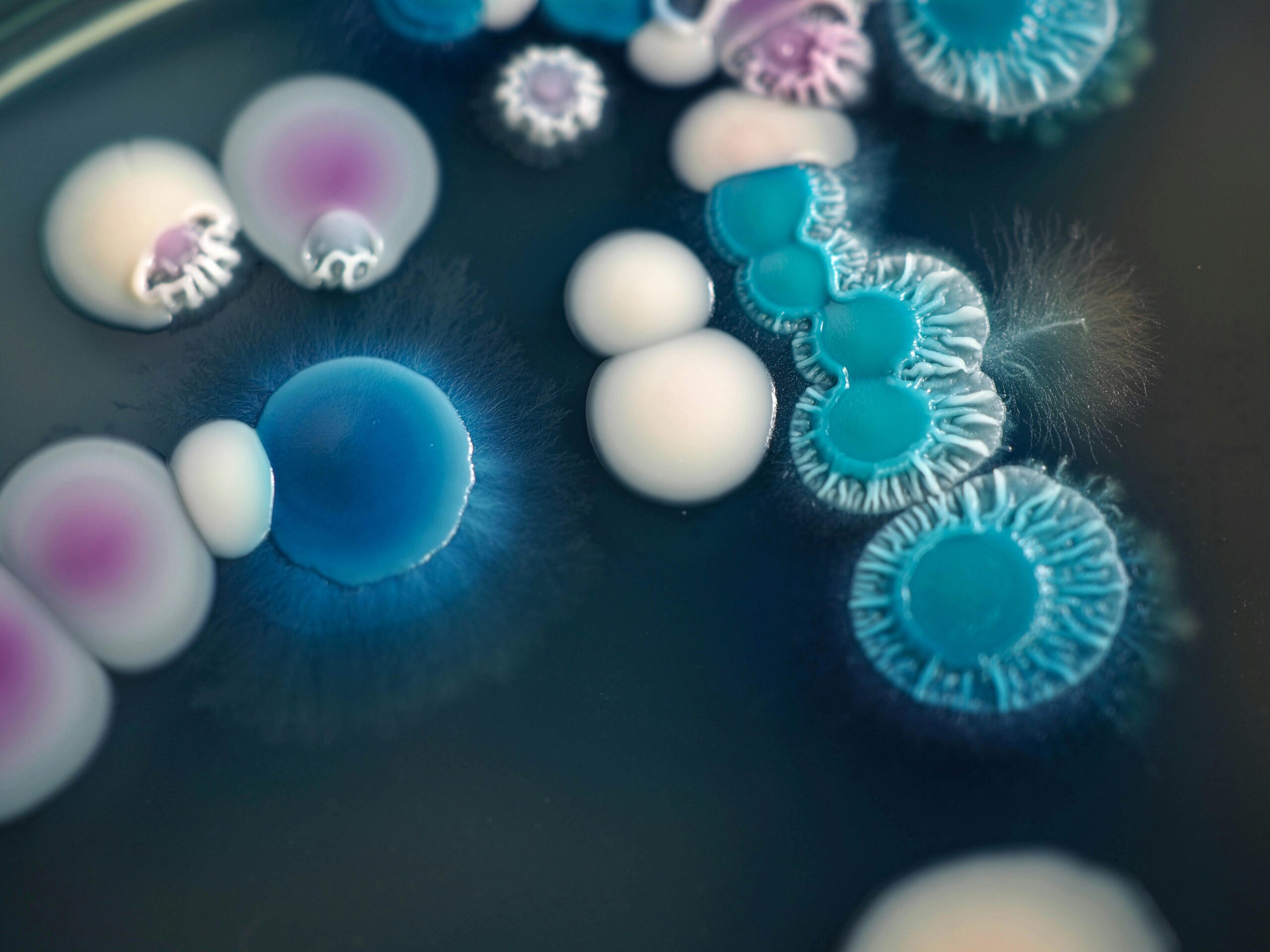

Several strains of Candida fungi grow on a plate. One member of the family, Candida auris, is an increasing infection threat that is often resistant to antifungal drugs. [Credit: Masakazu Sasaki | Unsplash]

Every year, more than 1 billion people develop a fungal infection and nearly 4 million die from it. But the arsenal of available treatments is limited: only 17 antifungal drugs are approved worldwide to treat systemic infections.

Those drugs fall into just four classes — in other words, they all rely on the same four mechanisms to treat fungal infections, a dependency that contributes to rising resistance to antifungal treatments. Rising resistance means there aren’t many treatment options for people who have fungal infections.

But the news isn’t all bad. While it’s been two decades since a new class of antifungal drugs entered the market, there is now at least one promising candidate in the pipeline — a new class of treatment that might even avoid the side effects of other antifungals.

Olorofim, developed by U.K.-based F2G, was passed over in 2023 by the Food and Drug Administration, which cited a need for more data. Just a few months ago, F2G announced $100 million in funding for continued development of the novel therapy, which is in clinical trials now.

But, despite a relative lack of treatment options, very few antifungals get as far as Olorofim.

Getting new drugs through multi-year trials to win final approval from regulators is an expensive, difficult process, but drug companies also face an internal hurdle: they need to know profits will be large enough to justify many years of development, according to Asiya Gusa, a microbiologist at the Duke University School of Medicine.

“That’s the hurdle — having high enough demand that companies want to invest in this,” Gusa says.

“It’s not your next Ozempic or Viagra or billion-dollar drug,” agrees Dr. David Boulware, a physician-scientist at the University of Minnesota who studies cryptococcal meningitis. “It’s super essential for those people to get it, but you’re not going to make a whole lot of money, or you’re gonna lose money. It hasn’t been a real profit driver for drug developers.”

Fungal infections are on the rise globally and in the United States. Exact infection numbers don’t exist due to underdiagnosis and underreporting, but the leading severe fungal infection in the United States, Candida auris, has soared from just 51 reported cases in the U.S. in 2016 to 4,514 in 2023.

Even with the steep rise in cases, it is difficult to find enough willing participants to conduct a drug trial, says Dr. David Denning, principal investigator at the University of Manchester’s fungal infection group. Another complication is that many of the people who get fungal infections are already immunocompromised, such as cancer patients or people who have recently had an organ transplant.

For those who do catch a fungal infection, it’s often not diagnosed immediately, making it harder to treat, says Denning. “One of the problems with doctors generally is that they think, ‘Oh, a patient is unwell, give them an antibiotic,’” he says. “They’re given antibiotics, and three, four, five days later, when things aren’t getting better, they think, ‘Oh, maybe it’s a fungus.’ And then they start to send tests, and by then it’s too late because the fungus has taken off and it’s late-stage.”

Side effects are often an issue for antifungal drugs, too. Both human and fungal cells are eukaryotes, which means they have a nucleus that holds the cell’s genome. Because of this similarity many drugs that target fungi also affect human cells, triggering gastrointestinal issues and headaches. One way around this may be to have future antifungals target the fungal cell wall because human cells have membranes instead of walls, says Norman Van Rhijn, a microbiologist at the University of Manchester.

Social stigma may also play a role in preventing further development of new antifungals, experts say. “It has an ick factor, so people don’t really talk about it as much as bacterial or viral infections,” says Gusa. She pointed to the 2023 TV series “The Last of Us,” in which a fungal pandemic causes society to collapse. “It has raised public awareness,” Gusa says. “Now I can talk to almost anyone, and I’ll be like, ‘yeah, have you seen ‘The Last of Us’?’ It’s a great lead-in. It’s actually a great cultural touch point.”

That said, the fungal infection in “The Last of Us” is a touch more dramatic than the infections happening in the real world. So, don’t worry, your infected neighbor isn’t going to turn into a violent, mushroom-possessed zombie. Real-life fungal infections manifest in many different ways, ranging from skin infections like athlete’s foot to life-threatening fungal infections.

While they can be extremely serious, for the average person the risk isn’t very high, Denning says.

“There are tens of thousands of fungi that live in the environment, and most of them don’t really cause a problem unless you’re really severely immunocompromised,” agrees Boulware.

For those unlucky enough to catch a severe fungal infection, though, the treatment options are limited. For example, C. auris is increasingly resistant to many antifungal drugs. This means the drugs doctors give patients with this infection either don’t work or become less effective over time.

Additionally, climate change, international travel and the overuse of existing medications are all combining to drive the global rise in hard-to-treat fungal diseases. There are also geographically tied infections and new species emerging that historically didn’t cause infections.

Another way fungi can develop resistance to antifungals is through overuse: when a certain drug is used too frequently, fungi can evolve ways to protect themselves from its effects.

“Once you expose organisms to drugs, they are smart. They try to really live with it,” says Mahmoud Ghannoum, the director of Case Western University Hospital’s Center for Medical Mycology.

One example of antifungal overuse is the case of Trichophyton indotineae, a common skin infection found first in India, Ghannoum says. The fungus that causes the infection is very resistant in India and, because of international travel, resistance is spreading to other parts of the world, he says.

Climate change is also contributing to the problem, a growing body of evidence suggests. Though it is hard to draw a direct connection, recent research has shown the areas in which certain fungi can live has expanded with changing temperatures and that some fungi are evolving to survive in warmer environments.

This shift has implications for human infections because most fungi cannot survive in the human body’s normal temperature of 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit, but that could change as more fungi evolve ways of adapting to warmer climates, says Duke’s Gusa.

Resistance can also come from agriculture. Many of the fungi that infect humans also can infect crops. The widespread use of fungicides to protect those crops can then lead to increased antifungal resistance when the same fungi infect humans.

One of the first places this effect was documented was in Holland — the tulip industry used a lot of one family of fungicides, and, eventually, experts noticed increased rates of resistance to similar drugs in humans. “It’s collateral damage,” says Denning.

Olorofim, the novel antifungal currently in development, may run into this same issue. There is a fungicide called ipflufenoquin, used on fruit and nut trees in the United States, that targets the same part of the fungal cell as Olorofim.

“By the time [new antifungals] come to market, we may have already lost them, or they may not be very effective for very long” because of pesticide use, says Boulware.

F2G has expanded the Olorofim study to include twice as many patients as the original study and plans to submit a new drug application.

With infections and drug resistance on the rise, experts like Gusa are anxious for more treatment options. “Our arsenal of antifungal drugs has really not changed. We haven’t increased with other drugs for many decades now, and the existing antifungals that we do have are actually quite toxic,” Gusa says. “We also need to improve the current standard of care, and that does mean more antifungal drugs.”

1 Comment

my foot was stamped on in a brawl when I was 40. I am now 75 and I believe my athletes foot has spread to my foot calf and hip. I would take part in a trial of olorofim