What? Hearing loss on a noisy planet

Anyone can experience noise-induced hearing loss — here’s what you need to know

Mark D. Kaufman • January 9, 2017

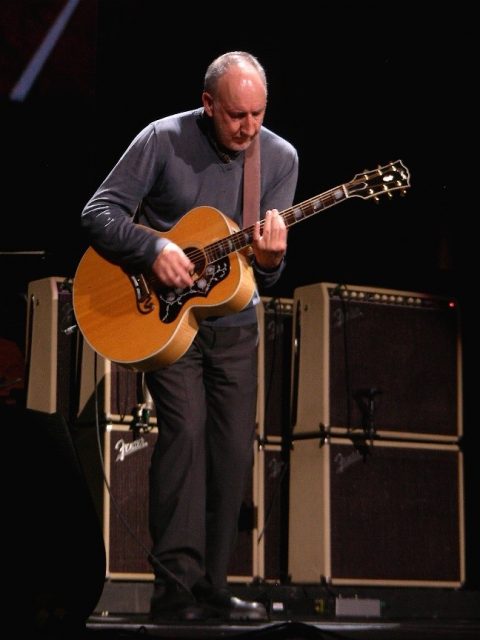

According to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, one in eight people in the U.S. over the age of 12 has hearing loss in both ears. [Image credit: flickr user Nick V. | CC BY-SA 2.0]

“Rock and roll caused it,” explains Chuck Conaty, confident that his hearing damage occurred while listening to the amplified sounds of The Doors and Jefferson Airplane in the 1960s.

In the years after his high-decibel youth, Conaty refused to believe that his hearing had dulled. He even managed to become a successful sound engineer in the Hollywood movie industry. Chuck’s moment of acceptance — what he calls his “Waterloo” — finally came while sitting between two Academy Award winners at the Northpoint Theatre in San Francisco.

“We were screening “Indiana Jones: Raiders of the Lost Ark”. There was a scene where Indy had just come back from the jungle. He was taking his old car down a tree-lined street, and they said, ‘You know, Chuck, the cicadas just don’t sound right.’ And I said, ‘What cicadas?’ ”

Although everyone loses some hearing with age, intense noise — whether coming from headphones or the amplified world — can cause permanent hearing loss decades earlier than expected. A recent German study found that professional musicians were nearly four times more likely to experience noise-induced hearing loss and ringing in their ears than non-musicians.

Beyond music, there is little reprieve from repetitive exposure to dangerously loud noise: traffic, subways and loud work environments are all potentially harmful. Even young ears can experience early hearing loss. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that over one in ten children have dulled hearing caused by excessive noise.

In the noisy 21st century, there are many ways to damage our hearing. Whether you think you have damage, are unsure or are just curious, here’s what you need to know.

What sounds are too loud, and how can I prevent them from damaging my hearing?

Hearing expert James Battey suggests wearing tightly fitting earplugs at concerts. [Image credit: Pixabay | CC 0]

Noise from heavy city traffic and subways also fall into this category, according to the NIDCD. A study in the Journal of Urban Health found that the average noise level on a New York City subway platform, measured when the train is coming into the station, is 85 decibels and can reach as high as 106.

Concerning today’s headphones, “it’s wrong to say there’s a problem with earbuds per se, but the volume can be much too loud,” says Battey. “If you can hear someone’s headphones from an arms-length away, that volume is too high.”

After a loud night next to a band’s drum set, you might experience a temporary dulling and in the coming days regain the auditory clarity that you’re used to. But Battey emphasizes that “noise-induced hearing loss is cumulative, so you might not appreciate it for a number of years after exposure.”

Prevention is simple, obvious and perhaps inconvenient: “If you’re going to go to a rock concert, you might not want to be there for more than a couple hours. Wear ear protection,” says Battey.

Hearing Trouble: The Curious Case of Pete Townshend

In 2012, one of rock and roll’s more aggressive guitarists, Pete Townshend of The Who, walked off stage mid-song. It wasn’t an act of rebellion. It was a show of concern for his hearing. The sound was too loud.Townshend suffers from debilitating tinnitus — ringing in the ears — and is mostly deaf in one ear. But he doesn’t blame live music. He blames headphones.

Writing in his online diary in 2005, Townshend revealed in stark terms that “[he has] hearing trouble” and that “Earphones do the most damage.” Townshend spent most of his career in the recording studio, scrutinizing tracks on headphones. He can speak only of his experience, and he acknowledges that it may be studio headphones, not those from an iPod, that cause the greatest damage.

But the real risk lies in the volume you choose, according to Battey.

When should I consider getting tested for possible hearing loss?

“Common, everyday situations are the best indicators,” says Battey.

For instance, if you’re in a loud restaurant and everyone at the table is enjoying the conversation, but you’re struggling to hear it, says Battey. Or, if you’re sitting around watching television and you’re the only one that wants it turned up.

There’s also an indicator that won’t leave you wondering: tinnitus.

“Ringing in the ears, tinnitus, is absolutely a symptom of a damaged auditory system,” says Battey. This type of ringing lasts for long periods of time. It’s not a temporary sensation, like what one might experience after a gunshot.

When do doctors test for hearing loss?

Unless you ask, a doctor will probably only screen you for hearing loss if you’re over 50 years old and show difficulty hearing. This is typical, as many screenings aren’t recommended for younger people.

The U.S Preventive Services Task Force, a group that makes recommendations about screenings, otherwise recommends that testing only be done if someone perceives and actively articulates concern for their hearing.

What is it like getting screened?

“It’s quick and painless,” says Battey. “It involves someone introducing sound into your ear at progressively lower intensities until you can no longer hear the sound.”

Adults with healthy hearing should be able to hear sounds at 25 decibels, says Lynn Gilbertson, who studies hearing science at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater. This is about the sound of a whisper. Normal conversations takes place at around 60 decibels.

The cost of a screening varies, but it’s relatively cheap because it can be conducted by a nurse, not an audiologist. Even without insurance, Gilbertson estimates that a screening would cost no more than $50.

What if my screening shows that I may have hearing loss?

Then comes a more thorough test called a hearing evaluation. This is administered by an audiologist, but it is also short, lasting around 10 minutes. You will be asked about your medical history, and the audiologist will peer into your ears using a light. Lastly, the audiologist will conduct a series of tests to see how your ear organs are functioning. For instance, an audiologist will push air into your ear canal to check if it’s obstructed by earwax, been punctured, or moving too much or too little.

The goal here is to determine the severity of hearing loss, the cause and treatment options. The evaluation might reveal that you don’t actually have hearing loss. For those without insurance, Gilbertson estimates that a hearing evaluation would cost between $100 and $200.

What are my treatment options?

The most common treatment is the one you see regularly: hearing aids. A licensed physician — likely the one that gives you a hearing evaluation — must clear you to purchase a hearing aid. There are many types, but they all carry a miniature microphone to pick up the sounds that you can’t hear. Your doctor will help you decide what works best for you. The two major government health programs, Medicare and Medicaid, do not pay for hearing aids. The devices range in price, generally between $200 and $700.

For half a century, hearing aids have helped Don Doherty overcome his hearing loss. Doherty was just 20 years old when he suffered profound hearing damage.

“In Vietnam I was exposed to lots of rifle fire, but we didn’t wear hearing protection in Vietnam, because on night patrol we needed to hear the enemy,” says Doherty. “It was a matter of self-preservation. We spoke to each other in whispers. Eventually, though, I was med-evacuated. I couldn’t hear anyone whispering to me.”

Today, Doherty can’t hear his alarm clock, so a vibrating clock stirs him awake each morning. But with the help of hearing aids, he carries on normal conversations.

But what if hearing aids aren’t enough?

For more profound hearing loss, a significantly more expensive, invasive treatment is available: cochlear implants. Unlike hearing aids, which amplify sound, the device is surgically implanted in the inner ear to function in place of a damaged cochlea — the “organ of hearing.” Although the surgery involves some risk, serious side effects are rare, occurring less than two percent of the time. They include wound infection from the surgery and accidental misplacement or removal of the implanted electrodes. The procedure, according to the NIDCD, “does not restore normal hearing” but “can give a deaf person a useful representation of sounds in the environment and help him or her to understand speech.” Without insurance, this procedure could cost up to $100,000, which is 500 times more expensive than a cheap hearing aid (around $200). But unlike hearing aids, Medicare and Medicaid provide some coverage for the treatment.

Toni Barrient, who has a cochlear implant in her right ear, calls herself “a bionic woman — at least on the right side.” She also wears a hearing aid in her left ear. Barrient can identify the exact evening she damaged her hearing. She was about 20 years old at a nightclub, “dancing in front of speakers that were taller and bigger than me.”

The next day, she says, “it felt like someone stuffed cotton in my ears.” Although Barrient’s hearing did improve, the damage proved irreversible. In her late 40s, her hearing deteriorated so dramatically that she sought treatment.

Barrient says she’ll never forget that initial, telltale blast of sound. “My hearing was never the same.”

**Editor’s Note: This article has been updated. It previously listed the threshold for potential hearing damage at 80, not 85 decibels.**