Protecting the other two thirds of the globe

Countries look to large marine protected areas to conserve our oceans, but the devil is in the details

Harrison Tasoff • April 5, 2017

Oceans cover 71 percent of the globe and contain 99 percent of the planet’s living space. Illustration by Harrison Tasoff. [Image sources: Flicker user Reinhard Link, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0; Daniel R. Strebe, CC BY-SA 3.0]

The way we protect the ocean is changing — in a big way. Ocean conservation is shifting from smaller, coastal reserves toward large marine protected areas in a rush to curb our growing influence over even the most remote places on our planet. Just last summer President Obama expanded Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in Hawaii into the largest protected area on Earth.

Marine protected areas (MPAs) are like national parks but in the ocean. They fall into two broad categories: smaller, near-shore parks and large, remote parks. The idea is to provide safe havens for animals to grow and breed. When managed effectively, MPAs increase the health of ecosystems.

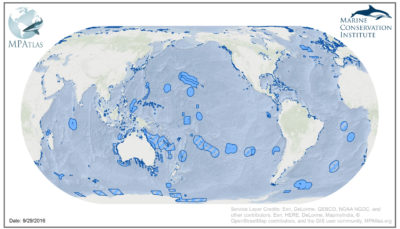

With only 2.8 percent of the ocean protected today, the easiest way to gain ground, or rather water, is by establishing large MPAs in areas where there is less resistance from fishing and oil industries. These increasingly large and remote marine protected areas bring new promises and challenges to conservation efforts. They cover vast territories where people are few and laws are hard to enforce. But some scientists worry that the large reserves distract us from protecting coastal waters.

Most human activity takes place in coastal waters near large population centers, which concerns scientists like Rodolphe Devillers, of the Memorial University of Newfoundland in Canada, who thinks that we have neglected tricky areas near the coasts in favor of largely unused remote waters. “Out of the thousands of MPAs that exist, 10 of them … account for more than 53% of the world’s total MPA area coverage,” Devillers wrote in a 2014 paper.

Samantha Murray, a member of the Federal MPA advisory committee, has similar concerns. “The fear is that these remote MPAs go in and people, they cheer, they open the champagne, and they walk away,” Murray says. In contrast, marine protected areas near the coast can leverage resources on land, like state wardens, law enforcement, and local scientists, in a way that remote MPAs cannot, says Murray.

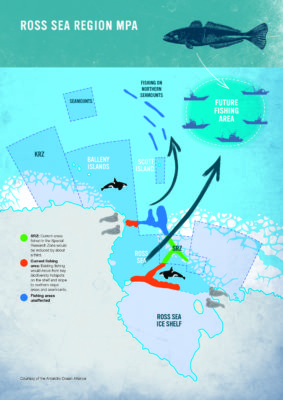

Even so, many newly established marine protected areas are large and remote. At least 15 sites larger than 35,000 square miles — bigger than Indiana — have been established since 2000. Last October, the world’s largest MPA was established in the Ross Sea off the coast of Antarctica, south of New Zealand. The Ross Sea Marine Protected Area encompasses nearly 500,000 square miles of international waters — an area larger than South Africa — and will officially take effect December 2017.

Large parks far from land account for most of the world’s protected water. The Ross Sea MPA is at the bottom of the map in the center; it’s stripes indicate that it has not yet been implemented. [Image Credit: MPAtlas.org. [11/2016], provided for non-commercial use]

For instance, the United States’ marine sanctuary system generally outlaws oil and gas drilling, but it rarely prohibits fishing. “It gives you kind of a pause as to what ‘sanctuary’ means in this context,” says Lance Morgan, president of the Marine Conservation Institute.

Bottom trawling, possibly the most destructive fishing method, is widely practiced in US marine sanctuaries. Trawl nets are dragged across the seafloor, scouring the sea bed of all life. “It’s kind of disturbing,” Morgan says.

Morgan does not share Devillers’ cautiousness regarding remote MPAs. “I don’t think it’s a distraction at all,” he says. There isn’t a lack of effort to protect coastal regions, it’s just harder to make progress there, he adds. Currently it is politically easier to gain protection for large remote areas, and Morgan sees no reason not to take advantage of this.

Others think vulnerable marine areas should be managed to allow both fishing and preservation, rather than establishing uncompromising protection over vast swaths of ocean. “For such an enormous area like what’s off Hawaii … particularly when so many people have worked so hard for sustainability in those areas, to have that brushed aside for the protection value, I find that troubling,” says Steve Scheiblauer, who serves on the Pacific Fishery Management Council and has been a harbor master in central California since 1978.

The country’s eight Fishery Management Councils are composed of a variety of stakeholders, from environmentalists to scientists and fisherman to American Indians. This diversity is crucial, according to John Holloway, who represents fishermen on the Pacific Council. “If the impacted people are part of the policy that’s decided then they would automatically, through pride of authorship, comply with the regulation,” he says. Holloway adds that marine protected areas can be beneficial as long as everyone they impact is involved in the process.

Large MPAs in international waters, like the Ross Sea, will necessarily involve robust collaboration. The Ross Sea MPA was proposed by delegations from the Unites States and New Zealand to the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, an international body that monitors the Southern Ocean. The Antarctic commission has 25 member nations, so there are a lot of people with eyes on this project.

But international collaboration is a mixed blessing, as the patchwork governance of the high seas also makes it difficult to establish protections and reach consensus. The UN is currently negotiating a new treaty for the high seas to address some of these issues. Discussions, which began in 2015, are slated to conclude this June.

MPAs within a country’s borders face issues of their own, and each is unique. For instance, Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in northwestern Hawaii comprises nearly 600,000 square miles of remote, uninhabited area in a relatively wealthy country. In contrast, the Palau National Marine Sanctuary entirely surrounds the small Pacific island nation, where many people rely on the ocean for their food and livelihood.

But Palau has invested in a strong plan. According to Keobel Sakuma, the Palauan sanctuary’s executive director, his country will close 80 percent of the park to fishing, while the other 20 percent is left open to regulated fishing for Palauans. “No export,” he writes.

Removing commercial pressures should strengthen the ecosystem, which will better serve local, subsistence fishermen and the growing market for ecotourism. Palau has even established new revenue streams to supplant the decline in fishing and set aside funds to finance the MPA.

Community involvement like that in Palau is hard to replicate in remote areas, but not impossible. Although no group of people call Antarctica their home, a community of scientists and fishermen do work in the frigid Ross Sea. In fact, the main goal of protecting the region is to safeguard the marine wilderness for future scientific research, says George Watters, the United States’ science representative to the Antarctic commission.

The Ross Sea Marine Protected Area is designed to protect a pristine marine wilderness. [Image Credit: Antarctic Ocean Alliance, included with permission]

Scientists, law-abiding fishermen, and officials from the Antarctic commission’s member countries will be looking for illegal activities in the Ross Sea, says Watters. The community of illegal fishing vessels is somewhat known, Watters says. And “those vessels have to come into port at some time,” he adds.

The Ross Sea MPA is an experiment. The agreement ends in 35 years, and the future is as uncertain as ever. But Watters thinks the scientific value of the reserve will encourage nations keep it protected. “You can do things and achieve things in Antarctica that you can’t necessarily achieve elsewhere, and I think that spirit will be there, regardless, in 35 years’ time.”

2 Comments

An amazing piece and so much knowledge for all.

Good introduction to MPAs. I feel another article would be useful for explaining MPA networks.