The noise mapper

A minority in many ways, Erica Walker is determined to find how urban noise affects human health

Cici Zhang • June 26, 2017

Erica Walker is the only person who studies urban noise at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health. [Image Credit: Julio César Román]

There are no truly quiet nights in Dorchester, Massachusetts. The constant hum of nearby traffic makes that impossible. But most nights are at least calm — unless a police car is approaching, lights flashing. On this summer evening, a resident has called the cops on a suspicious black woman standing in front of his house. She’s holding something in her hand, pointing it in various directions.

That something is a sound meter, as the resident and the police would later learn. And that black woman, a Ph.D. student at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, is waving it around because she’s monitoring noise levels in the neighborhood — even if someone calls the cops on her. Erica Walker, the noise mapper, won’t be deterred from doing her work, even in predominantly white areas of Greater Boston.

Walker made a splash in October 2016 by publishing an unprecedented noise report on the Boston region, assigning failing grades to 11 of the 13 neighborhoods she assessed, including Dorchester. Walker’s goal is to raise awareness about how constant urban noise is affecting people’s lives and health. While research has firmly linked noise to sleep disturbances and stress-related health problems, very few scientists have studied noise in urban neighborhoods. Walker’s report is the first large, citywide survey done in the United States.

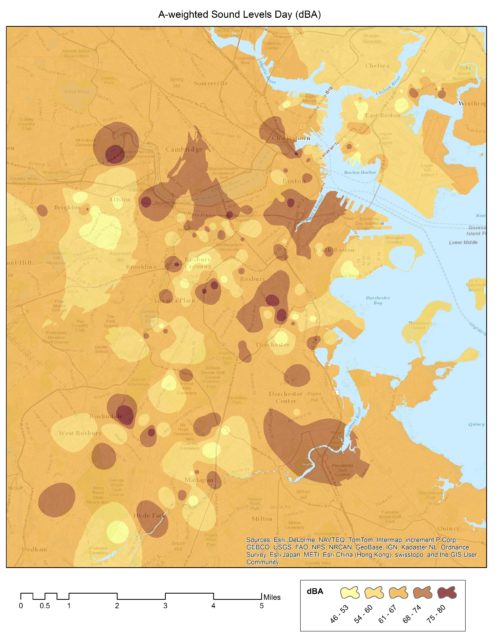

Walker, who describes herself as a former sufferer of constant noise from her neighbor’s kids, is passionate about her project. She’s biked to 400 different locations in the Boston metro area, covering over 3,000 miles. And she’s had little guidance along the way — no researcher at Harvard studies noise in the way she wants to. Together with an artist and a geographer, Walker turned 1,200 of her noise surveys into digital maps charting noise levels, residents’ perceptions of noise, and the impacts of noise on health. The team’s Noise and the City website also includes portraits of, and interviews with, residents who have struggled with noise — doctors, dancers, teachers and many others.

“I’m just here to listen to what people complain about, what bothers people and try to find solutions,” Walker says. “I’m not here to try to discover the next great thing. That’s not my role in life.”

When I Skyped into Walker’s apartment in Brookline, Massachusetts for an 11 a.m. interview, the first thing I heard was a merry laugh, and then, “Can I not turn on my camera? I just woke up. I’m a mess.” Finally, the 37-year-old turned on the camera and there appeared her round face, caring eyes and short braided hair.

After learning about her grinding daily schedule, I was glad she slept in that day. It’s not fun to get up at 3:30 a.m., bike to the office and work for hours before teaching at 8 a.m.

All that effort paid off with the release of her noise report, which was the subject of several news stories in places like The Boston Globe and The Atlantic. She also won the respect of her colleagues in the Boston research community.

“Before completing her Ph.D. she has done something that’s never been done in the [United States] before,” says Dr. Rohit Chandra, a psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital’s Chelsea location. They became friends when Walker approached him after a lecture to ask whether chronic noise could actually cause physiological stress. “I said, ‘Yeah absolutely’,” Chandra recalls.

There’s good evidence, Chandra says, that noise could affect the stress hormone cortisol. Specifically, several studies show that noise exposure releases the stress-creating chemical. Noise can also impact the sympathetic nervous system, which regulates heart rate and blood pressure, thus increasing the risk of cardiovascular diseases. Previous research has looked at how noise from airplanes affects people who live near airports; Walker’s study is helping to do the same for the buzzes, honks and rumbles of everyday life in the rest of the city.

A key to her success, Chandra says, is that Walker “really did a very nice job of pulling people in … Whatever expertise she did not have she does a great job asking people who do have it.”

Marcos Luna, a geographer at Salem State University, is one of the experts recruited by Walker. He co-authored the noise map report along with Walker and an artist named Julio César Román, who also designed the project’s website.

When Walker visited Luna’s house to measure noise levels — his wife had seen a posting from Walker on their neighborhood’s Facebook group — Luna got excited about her project. He studies environmental justice and knew that lower-income communities are especially noisy.

Walker certainly left an impression on Luna. “To tell you the truth,” Luna says, “being a woman of color doing scientific research like that is very encouraging because I don’t see a lot of women in science [to start with]. That was impressive.” He’s right: Only 2.7 percent of early-career Americans with a doctorate in science and engineering are black females, according to the latest report by the National Science Foundation.

One of Walker’s noise maps shows the sound level (dBs) in Boston during the day. [Image Credit: Marcos Luna]

Although the family struggled financially, Walker’s mom used to take her to the public library in Jackson, a place she still remembers. She later left tiny Mendenhall for Boston to attend Simmons College, where she majored in math and economics.

After college, Walker ran her own furniture design business for nine years but struggled to make ends meet. After she used up her rent money to attend a craft fair but didn’t sell anything, Walker decided to abandon that life and went back to school — at the age of 31.

Having suffered years from the annoying sound of her neighbors’ kids running around upstairs, Walker decided to learn more about noise and cities. She first got a master’s in urban and environmental policy at Tufts University, and then the Ph.D. at Harvard.

But it was not realistic to learn all the unique skills she needed for her noise project, so Walker — who isn’t shy about asking for help — decided to assemble a team. When she realized she needed a mapping expert, for example, she found Luna the geographer and asked him to join the project.

Walker’s persistence paid off. “When I first started this project, my goal was to have 10 surveys. I was like if I have 10 surveys I will be happy.” Walker says. In the end, by attending community events, promoting on social media and reaching out to city officials, she was able to collect hundreds of surveys, launch the website and published a detailed analysis of her data.

“This project has turned into something that is beyond anything I could have ever imagined,” she says.

Walker discovered that although there were large differences in the noise level between neighborhoods, from the quietest 50 decibels to the loudest 90 decibels, a staggering 74 percent of survey participants reported trouble falling asleep because of neighborhood noise.

Surprisingly, people’s perception that “this area is so noisy” didn’t always match the measured level, especially in East Boston. “The noise in East Boston wasn’t too unlike other neighborhoods,” says Walker. “However, when you look at the perception of loudness, residents in East Boston rated their neighborhood to be really high.” These residents mostly complain about the noise from the airport.

Going forward, Walker hopes her noisescape results could inform cities to “move beyond noise ordinances,” rules and laws that limit the level and time of any noise. Although the ordinances are enforced by local police departments, little is known about “how the noise ordinances are followed and broken” and “the actual noise climate of the city,” like the prevalence and the distribution of urban noises, says Walker. In the future, more research should be done to identify the chronically loud areas, and then apply noise control practices.

For example, Walker says solutions like planting more trees and shrubs are potentially helpful because they block and absorb noise. “Research has shown that vegetation greatly reduced low-frequency noise, which many people complain about,” she says. According to Walker, low-frequency noise, in the range of 30-250 Hz, includes the vibrating sound emitted by a passing bus.

“There’s a lot of levels of what could be done,” such as installing sound barriers next to highways, says Doug Brugge, an occupational and environmental health specialist at Tufts University School of Medicine. “There’s also planning,” he says. “You can always do planning to not to put a truck route through the residential neighborhood.”

Brugge has mentored Walker since her days as a master’s student and thinks of her as a bold risk taker. “[T]his is an area with limited amount of research on and she has decided to pursue some aspect of it that’s even less well-studied,” he says.

Walker submitted her doctoral thesis in April, and now hopes to keep studying the issues her study raises: How does noise affect human health? And how do the health effects change based on people’s psychological perceptions of noise?

Whether she’ll stay in academia or start her own noise-oriented business is still up in the air, but Walker’s not going to stop. She wants to continue her work, making sure it remains up-to-date and relevant to the community.

Right before our Skype chat, Walker told me, she was listening to a song called “Mother” by Enigma, a popular group that debuted in the 1990s. “When I was lying in bed this morning I was thinking about next steps …” she says, “and there’s a lyric in the song that just really spoke to me, like, everything is going to be ok.” The lyric goes like this:

“It´s time you cross the river to glory land

Any dream helps survive

When you are there, you will see

That´s the place you long to be.

Trust me, this ride is free.”

2 Comments

When I recognize that I am tense without knowing why, I can almost always trace it back to noise – a television that is too loud, or a bathroom fan that is still on. When I lower the noise level, my stress melts away!

Erica, your work in this area will no doubt be used for generations to come. What a brilliant idea to map it. Thank you for embarking upon the journey and seeing it through!