Chemical ‘aphrodisiac’ jumpstarts the sex life of a single-celled organism

Yes, it's as messy as it sounds

Brianna Abbott • January 22, 2018

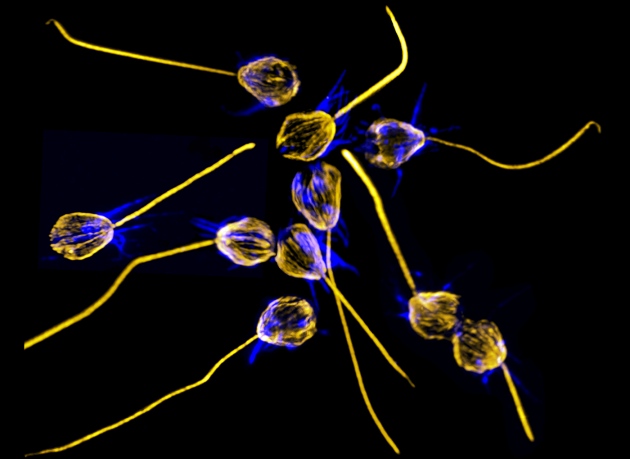

The single-celled S. rosetta swarm together and get busy in the presence of the bacteria V. fischeri. [Credit: Arielle Woznica].

Bacteria help other organisms, including humans, with processes such as digestion and combatting disease. But now they’re sliding into a more scandalous territory — sex.

The bacteria Vibrio fischeri triggers mating in the single-celled organism Salpingoeca rosetta, according to a study published recently in Cell. The finding represents the first known instance of bacteria putting another species in the mood for sex and could become a model for studying the origins of animal sexual reproduction, according to study author Arielle Woznica at the University of California, Berkeley.

S. rosetta is a choanoflagellate, a bacteria-eating blob that moves through global waters with its tentacle-like appendage. Because choanoflagellates are the closest living relatives to animals, researchers use them to study the evolution of animals from single-celled organisms. That’s what Woznica was doing in Nicole King’s lab at University of California, Berkeley.

Wanting to determine if S. rosetta responded to different types of bacteria in different ways, she mingled the choanoflagellates with an array of bacterial species — and that’s when she saw something sultry. Once she introduced the bacteria V. fischeri to the S. rosetta, the choanoflagellates clustered together.

“When I first observed the swarming, I didn’t really have any idea of what it was indicative of,” Woznica says. “Nicole, my boss, was actually the first person who suggested that maybe this was mating. I thought, ‘This couldn’t possibly be the case. That would be crazy.’” She wasn’t ready for how crazy S. rosetta could get.

The researchers took two kinds of blob-like S. rosetta with different traits and induced reproduction —like locking people with either traits AB or traits CD in a room together and shutting off the lights. If the S. rosetta were abstinent, the traits would remain unmixed. If the organisms canoodled, some offspring would have new combinations of traits, like AD or BC.

And S. rosetta apparently aren’t shy around company. Their offspring had mixed traits, AD and BC, in the presence of the bacteria or anywhere the bacteria had been, meaning that something about V. fischeri did, in fact, inspire the choanoflagellates to get it on.

The bacteria had actually released an ‘aphrodisiac’ that caused the S. rosetta to cozy up, according to Woznica. That aphrodisiac is a protein, christened EroS after the Greek god of love. And although the exact reason the V. fischeri sent EroS into the sea is unknown, University of Oklahoma molecular biologist Paul DeAngelis believes that protein helps the bacteria seek and break apart food. This mission eventually leads to the sexual reproduction of S. rosetta.

Here’s how the proposed foreplay plays out. The choanoflagellate secretes a long chain of sugar molecules, known as chondroitin. When the bacteria detects the sugar molecules, it sends out protein EroS to break up the long chains into smaller chunks, says DeAngelis. S. rosetta, however, eats the bacteria and notices EroS and the chewing of its sugar chains. The breakdown of their sugar chains signals that their food source, V. fischeri, is nearby. The abundance of food might make sex appetizing.

“Maybe it has something to do with ‘Oh, there’s a lot of food here, so what we should do is sexually reproduce and make more of ourselves and take advantage of this food source,” said biologist Mike Hadfield at the University of Hawaii.

The release of the long chain of sugar molecules, chondroitin, was previously confined to the animal kingdom, so King’s lab’s next move is to study the chemical signal’s complete function. The team also wants to explore whether bacteria-triggered mating occurs among other aquatic organisms, perhaps opening a new door on this closed-door activity.

1 Comment

Vibrio fischeri is famous for flashing; for bioluminescing. You find them in the eyesockets of Hawaiian squid — their Light Organ. I made use of them as indicators of how much oxygen is present, ie is there ANY oxygen present in the water/culture medium; with any oxygen at all they glow, via Luciferin/Luciferase. I can see it in the photo that Brianna has accompanying the article here. (for those whose knowledge of the famously glowing bug is olde, it’s the same as Achromobacter fischeri ie it was renamed Vibrio fischeri). Strangely, it’s like, the “wrong” color but that’s some kind of artifact. If you just look at a culture of V fischeri glowing, it”s about the coolest glowing greenish tint youve ever seen. It’s like a firefly but it’s not lit up like a bunch of fireflies, it’s a GLOW.