We need a better way to measure monarch populations

An iconic butterfly is in trouble – but how much trouble?

Lucy Hicks • April 4, 2018

The dark clumps aren’t just leaves—thousands of monarch butterflies hang from these trees in the Sierra Chincua Butterfly Sanctuary in Mexico. But the exact number of butterflies remains a mystery. Current measurements of monarch colonies could be more accurate, some researchers say. Photo by Lucy Hicks.

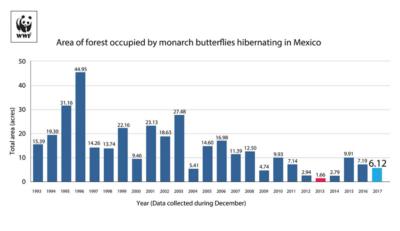

Tens of millions of monarch butterflies migrate as far as 3,000 miles every fall to spend the winter in the mountains of central Mexico. Clustering like penguins in the Antarctic winter, these butterflies form compact groups that weigh down branches and completely cover the bark on tree trunks. A few months later, the World Wildlife Fund announces the results of its annual monarch count. This year, they estimate that monarchs occupied roughly six acres of forest in the winter sanctuaries — 15 percent below last year’s measurements, and 86 percent below measurements from 1996, which is when monarch colonies started to shrink.

Because the monarchs are so tightly packed and there are so many of them, manually counting these butterflies to determine their population size is out of the question. Instead, the World Wildlife Fund quantifies the monarch populations indirectly by calculating the total area of land they occupy, says Eduardo Rendón, head of WWF’s Monarch butterfly program. These winter counts conducted by WWF are the best evidence that North America’s most famous butterfly is in sharp decline, but some monarch researchers wonder whether the winter census is as accurate as it could be.

No one disputes that the monarch is in trouble, but some scientists think the species may be in even worse shape than the winter counts suggest. The uncertainty is a big concern for scientists and advocates who are trying to organize a massive effort to help the monarch recover by protecting Mexican forests and planting hundreds of thousands of acres of milkweed and wildflowers all over the insect’s North American range. An accurate count of how many butterflies overwinter in Mexico would allow scientists to better estimate just how much milkweed needs to be introduced to support the returning monarch population next summer and fall.

The problem is that the current winter measurements only estimate the area these colonies occupy in the forest. WWF does not try to count how many butterflies are actually present, explains Lincoln Brower, an ecologist who is the dean of monarch researchers who has studied them for over 60 years. “I do think [the system] needs to be updated,” Brower says. While he believes WWF’s current measurements are accurate in measuring the areas of these colonies, “they haven’t taken into consideration the density issues.” If two colonies are the same size, but the butterflies in one colony are more tightly packed compared to the other, these current methods would count both colonies as equivalent.

Brower and other prominent monarch researchers believe that using newer technologies in the winter count, such as high resolution imagery, would yield a more reliable estimate of how many monarchs are really in the colonies. These newer tools could visualize and digitally analyze monarch clusters, helping scientists better understand the biology and numbers of these butterflies, ultimately leading to more effective conservation efforts. The monarch’s plight has captured the attention of millions of people and even the presidents of Canada, Mexico and the United States. In 2015, then-President Barack Obama, set a restoration goal of reaching nearly fifteen acres of colonies—roughly 225 million monarchs—by 2020.

“Setting that kind of goal, we want to be as accurate as possible, and it would be more accurate to have actual numbers [of butterflies], instead of just hectares,” says Karen Oberhauser, another veteran monarch researcher and the former director of University of Minnesota’s Monarch Lab.

Since 1996, WWF has recorded a noticeable decline in overwintering populations. Image provided by WWF.

Because their vast warm-weather habitat encompasses most of the continental United States and parts of Southern Canada, monarchs would be almost impossible to count if they did not concentrate in Mexico’s Transvolcanic Mountains every winter. Exactly why so many go to the same twelve locations every winter, and how they get there, is still largely a scientific mystery – all the more impressive because it’s only every fourth or fifth generation that makes the trip (monarchs live for only about a month during the spring and summer). The key attraction seems to be oyamel fir forests, typically 10,000 feet above sea level or higher, that constitute an ideal microclimate for these butterflies: moist and cool enough to slow their metabolism, allowing them to live six to eight months and survive through the fall and winter.

WWF-Mexico measures these monarch populations in early December, when the weather is coldest and the butterflies are packed together most tightly. Once the measurers locate a colony at one of the overwintering sites, they create a perimeter enclosing all the colonized trees using a compass and measuring tape. They also count the number of trees within this perimeter. From there, they can calculate the area, in hectares (one hectare is equal to roughly half of an American football field). WWF then adds the areas calculated from each reserve to find the total number of hectares occupied by monarch populations each winter.

What’s missing from these measurements is the density of monarchs, or how many butterflies are in one hectare, says Oberhauser. Many monarch researchers think, based on their own observations that the density of monarchs has decreased over the years. “When we use the area occupied by monarchs, we are really underestimating the size of the decline, because not only is the area getting smaller, but the density of the monarchs is getting smaller,” she says.

If Oberhauser is right and the WWF is overestimating the winter population of monarchs, then the monarch is in even worse shape than we realize, says Ernest Williams, a professor of biology emeritus at Hamilton College and retired butterfly ecologist. He reasons that a smaller population size may be leading butterflies to cluster less tightly, as there is not as much competition for space. Independent researchers have tried to estimate monarch density in the past, but estimates vary from 6.9 to 60.9 million butterflies per hectare, says Wayne Thogmartin, a quantitative ecologist at the United States Geological Survey. The most common density measurement from these past studies is about 21 million butterflies per hectare, which would translate to 52.5 million butterflies overwintering this year, but there’s no way to know whether that estimate is accurate.

We now have technologies that could record more accurate densities, Thogmartin says. Both Williams and Brower proposed flying drones over these monarch colonies, using high resolution imagery to capture the orange color on the trees. A more concentrated and intense orange color would denote a greater density of monarch butterflies; this would not give us an idea of numbers, but would give a better indication of how densely packed these butterflies are, and if these densities change over time. Light detection and ranging, or LiDAR, is already used to quantify bat populations in caves, and monarch researchers are currently adapting it to measure a much smaller populations of monarchs that overwinter in California. Researchers can use computer programs to translate LiDar imagery to colony volume, and from volume to actual number of butterflies, Thogmartin says. High resolution thermo-imaging, with further analysis from computer programming, could also generate more accurate counts of butterflies, he added.

“This technology used to be quite expensive, but now you can readily modify a smartphone camera to collect the relevant imagery, making the cost much more accessible, not to mention the increased ease of use,” Thogmartin said.

Collaboration with WWF-Mexico is key, however; due to an agreement with the Mexican government, only the organization and employees of Mexico’s Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve are allowed to measure these monarch colonies. Any upgrade to methodology would be done alongside the organization, Thogmartin said, adding that they are currently working together toward solutions.

While better measurements of monarch density will help researchers get a more complete picture of how populations have declined, scientists agree on the fundamental point: The WWF’s 23 years of data make it abundantly clear that the monarch is in trouble.

“You don’t need precision in the measurements to have an overall sense of what is happening,” says Williams. “We know there has been a significant decline.”

While having a better understanding of these populations would be ideal, Oberhauser says, “Our target restoration goals are just so large in the end that it is going to take all the restoration we can muster.”

1 Comment

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife recently published a story about LiDAR testing and monarch counts. For more information: https://www.fws.gov/cno/newsroom/highlights/2018/monarch_lidar_count/