A guide to cervical cancer screenings at every age

What to know before you go to your annual gynecology appointment

Jillian Mock • July 18, 2018

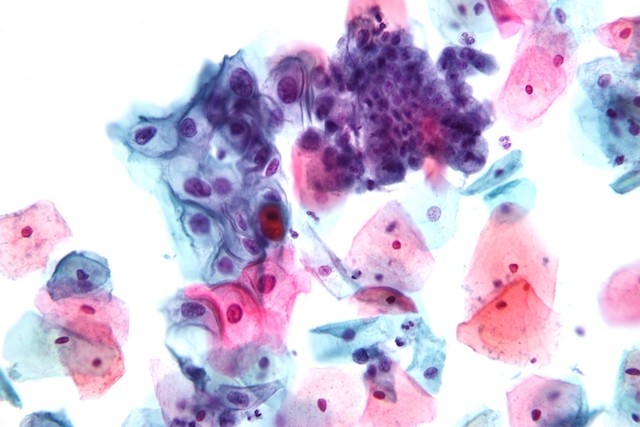

A close-up look at endocervical cells collected for a Pap smear test, including normal cells (purple, middle right) and abnormal cells (blue-purple, middle left) that are potentially pre-cancerous. [Image credit: Wikimedia Commons, Nephron | CC]

Like any health-conscious woman in her twenties, I begrudgingly go see my gynecologist once a year. I listen and nod while my doctor talks to me, all the while mentally preparing myself for the inevitably uncomfortable exam. I’m not keeping track of what exactly my doctor is telling me or how often I’m getting a Pap smear.

For me, getting through that appointment is all about survival.

Across the United States, women like me will be screened for cervical cancer every few years for most of their lives. These appointments and tests, unpleasant an experience as they may be, are critically important.

Close to 13,000 women develop cervical cancer and 4,000 die from it each year in the U.S., according to the American Cancer Society (ACS). But that number used to be much higher. The number of women dying from the disease nationwide has dropped 50 percent in 40 years thanks to widespread screening.

But guidelines for cervical cancer screening change with age, and it’s not always easy to keep up with them. Do you know what’s recommended? And, more importantly, is your doctor following best practices?

First off, what causes cervical cancer?

In the 1980s, scientists discovered that HPV — also known as human papillomavirus — was far and away the leading cause of cervical cancer. Women who developed cancerous lesions on their cervixes almost invariably also tested positive for unchecked HPV. Now, it remains one of the most common types of cancer in women.

“80 to 90 percent of us will be exposed to at least one type of HPV in our lifetime,” says Debbie Saslow, an oncologist and HPV specialist at the American Cancer Society. “Most of the time, that’s happening in the teens and twenties, because that’s mostly when people start having sex.”

Don’t panic. Most HPV infections will go away on their own. However, if the infection continues beyond one or two years, then it could eventually cause precancerous lesions that evolve into cervical cancer.

How often are we getting screened?

Today, about half of diagnosed cervical cancers occur in women who were never screened. And about 10 percent are in women whose last screening was more than five years before diagnosis.

The American Cancer Society, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force or USPSTF and other authoritative organizations analyze hundreds of studies to make recommendations about cervical cancer screening. The guidelines tend to be similar across all of them and are updated every few years with the latest scientific research.

Heads up: guidelines say women who have had their cervix removed in a hysterectomy should not be screened. The guidelines also say women with HIV or a weakened immune system should be monitored closely and potentially be screened more often than the suggested requirement for their age group.

Here is what you and your doctor should know about cervical cancer screenings at every age so you can stay happy, healthy and cancer-free.

Age: Below 21

Current recommendation: Should not be screened for cervical cancer

Cervical cancer is rare for women in their teens. Only 0.1 in 100,000 women between the age of 15 and 19 will get cervical cancer, according to the American Society of Cytopathology in their 2006 guidelines.

“In the twenties, the risk of cervical cancer is very small. Basically, we don’t recommend any screening less than the age of 21,” says Valentin Kelov, a gynecologic oncologist at Mount Sinai in New York.

Age: 21–29

Current recommendation: Screened every three years with a Pap test

It can take “years to decades” for an HPV infection to progress into pre-cancer and then cervical cancer, according to Saslow. Because of this, screening every year does little to reduce cancer risk.

But many women still get screened annually as a holdover from the 20th century, says Saslow. And that can also be problematic.

“The risk of annual testing is the risk of having more false positives,” says Carol Mangione, a primary care physician and member of the USPSTF.

Screening annually results in more than double the number of procedures to inspect the cervix, vagina and vulva compared with screening every three years. This, of course, does nothing to reduce the risk of cancer. Saslow even says that additional screenings and treatments can impact the cervix and lead to complications during pregnancy, including early delivery and having a low-birthweight baby.

Age: 30–65

Current recommendation: Co-testing with Pap test and high-risk HPV test every five years

Possible change: Co-testing not recommended; HPV test alone every five years or Pap test alone every three years

If you belong to this age group, you’re at the highest risk for developing cervical cancer.

The current best practice is co-testing: getting both a Pap test and a high-risk HPV test every five years, as stated by different guidelines. Both tests involve a pelvic exam to take a swab of cervical cells — but the HPV test picks up signs of the virus and the Pap cell abnormalities.

Remember, the HPV test is not an option if you’re in your twenties. “So many women in their teens and twenties would test positive for HPV that it would be a completely meaningless test,” says Saslow.

The HPV test is more sensitive than the Pap. A high-level critical analysis by the Cochrane Review, a nonprofit that evaluates medical research and health interventions, found that for every 1,000 women screened for cervical cancer, the HPV test will correctly identify 16 out of 20 women with cancer, whereas the Pap test will only identify 12. The review also found the HPV test would incorrectly diagnose 101 women and the Pap test would incorrectly diagnose 29 out of every 1,000 women screened.

This means the HPV test is better at catching cervical cancers than the Pap test, but there’s a trade-off, because it’s also far more likely to diagnose a false positive. False positives can lead to unnecessary testing, interventions and stress.

A draft update of the 2017 USPSTF guidelines released in October made one major change from 2012: It no longer recommended co-testing and instead said women should either receive a Pap every three years or a HPV test every five but not both.

Mangione, who was part of the team that updated the new guidelines, looked at recent evidence and long-term studies. They “showed us that the co-testing strategy did not lead to substantially more diagnosis of cervical cancer and it did not reduce mortality from cervical cancer,” she says. “What it did do was it increased the number of what we call the false positive test.”

Taraneh Shirazian, a gynecologist at NYU Langone Medical Center, thinks the HPV test might eventually replace the Pap test as the first line of defense.

“Instead of doing the test together, what if everybody just did HPV testing and then we decided who got a Pap?” Shirazian asks. “Then the HPV test would basically help us identify those at risk first and then we could look at the cells.”

Age: 65+

Current recommendation: Should not be screened for cervical cancer

If you’re older than 65, you may stop screening if your last three consecutive Pap tests or two consecutive co-tests were normal and completed in the last 10 years.

“Cervical cancer is still a threat for elderly women, or 65 plus,” Saslow says, “but most of those cancers are in women who have either never been screened in their entire life, or they haven’t been screened in, say, 10 or more years.”

Get screened, get treated

Now that I’ve started actually paying attention and I know what’s recommended, I can tell you I did not have to get a Pap smear this year because my last test was recent and clear. Ultimately, screening is a matter of weighing benefits and harms, according to Mangione.

“We don’t want to lose the big message: This is a highly effective screening test and all women really should get screened,” she says. What’s worse, most people who have cervical cancer today have not been adequately screened.

So, don’t ghost your gynecologist, as tempting as it may be to skip that annual appointment. Be a Goldilocks about cervical cancer screenings — not too often and not too far apart. By talking with your doctor, you can figure out the screening regimen that works for you at every stage of your life.