A flawed number that saves lives

Millions of people rely on the Air Quality Index, but experts say it’s a rough measure at best

Lauren Leffer • November 25, 2020

Photos of the same view 12-hours apart in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Smoke from the Creek Fire obscures the view in the second picture. [Credit: Natalie Walsh | CC BY-NC-SA]

Driving home from a recent backpacking trip, Natalie Walsh suddenly found herself amid thick plumes of wildfire smoke. “It was just totally apocalyptic … I literally had an asthma attack. I was choking.”

When she made it back to Los Angeles, the air wasn’t much better. “I started wearing an N95” mask, she says. “I’ve been keeping my windows closed and running the air filter ever since this started.”

But if you ask Walsh what she does most often to avoid the smoke, it’s checking the Air Quality Index (AQI). She pulls up the AQI on her cellphone frequently, “whenever anxiety spikes.”

Lately, there’s been plenty for Walsh and millions of others to be anxious about. With historic wildfires sweeping the Western U.S. and air pollution hitting record highs — experts say people are relying more than ever on air quality reports to protect their health.

“This [wildfire] event kind of caught everybody’s attention,” says Daniel Johnson, an air quality monitoring specialist at the State of Oregon Department of Environmental Quality in Portland, Oregon. “People were looking for good information and advice.”

But AQI, while useful, is an imperfect tool that doesn’t communicate everything users may think it does. Pollution levels can change quickly and vary by town or even neighborhood, but air-quality reports aren’t up-to-the-minute and there aren’t enough monitors across the U.S. to generate locally specific reports. The index itself, set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), isn’t based solely on health considerations, and thus doesn’t reflect the strictest air quality standards.

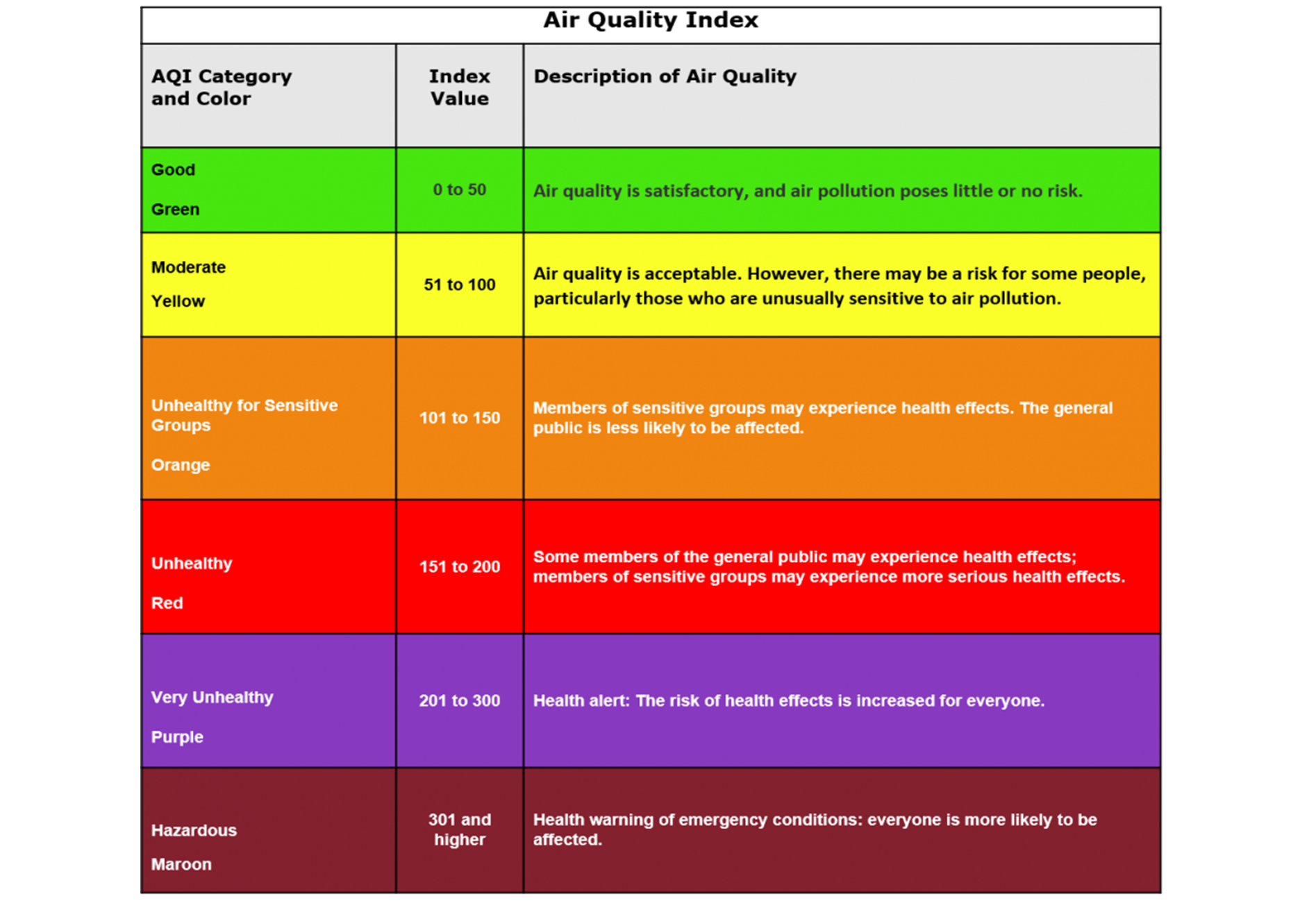

The AQI “isn’t necessarily 100% based on the science,” says Michael Brauer, a professor of public health at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. While the EPA looks at long-term health data when it reconsiders its air-quality standards, as it is required to do every five years, the agency also considers other factors, including the number of cars on the road and the financial impacts of tighter regulations on the energy industry. All of those factors in turn influence the AQI thresholds because when the EPA decides how much air pollution cars and coal plants are allowed to release, it is also setting the boundaries for each of the AQI categories, which range from “good” to “hazardous.”

The Air Quality Index (AQI) scale is generally set between 0 and 500, and values are displayed with a descriptor and a color. When the AQI algorithm results in a value beyond 500, as shown here in a report from Portland, Oregon, that pollution level is considered “beyond the AQI”, which means the degree of health impact is unknown. [Credit: Michael Radack | CC BY-NC-SA]

Particle pollution — one of the key pollutants regulated by the EPA under the Clean Air Act, and the primary pollutant produced by wildfires — also comes from car and power plant emissions. In reality, says Brauer, even very low levels of particle pollution can have health effects. “There is no level where we can really say there’s no [health] impact,” he says.

Those health consequences can range widely, affecting different people in different ways depending on their age and condition. “[Air pollution] can cause heart attacks, strokes, asthma attacks and has also been shown to raise rates of infant mortality,” says Maria Harris, an environmental epidemiologist at the Environmental Defense Fund.

The complete, six-level AQI scale. The accompanying color and descriptor are meant to make the index value easier to interpret. [Credit: U.S. EPA | Public Domain Mark 1.0]

Because there is no definitive safe level of many air pollutants, some states, such as Washington, have more stringent pollution regulations than the EPA. As a result, Washington uses a different scale that reports unhealthy air at lower pollution levels than the national AQI. For example, air that contains 20 micrograms of particulate matter per cubic meter is considered “unhealthy for sensitive groups” in Washington but “moderate” just over the border in Oregon or Idaho.

The resulting differences may confuse people who rely on the indexes, especially because there are several to choose from — including some, like IQAir — which provide global air quality ratings. Oregon’s Johnson says non-governmental sites like this may provide less accurate information and less frequent updates — often sourcing their data from the EPA anyway.

The EPA collects air quality data from about 4,000 monitoring stations across the country and uses an algorithm to distill that data to a single value for each monitor location and pollutant. The agency then reports those index numbers via news outlets, government websites and likely your phone’s weather app.

“The AQI is meant to be an easy to understand index that tells people how to respond,” says Johnson. “If [the AQI] is in the hazardous category, any short-term exposure can give you adverse health effects.” Notably though, the AQI doesn’t report a real-time value. The EPA averages and re-reports particulate matter levels every 24 hours normally, and every three hours when pollution levels increase via the agency’s NowCast website. If fires are raging, that may not be fast enough to deliver an accurate real-time assessment.

In addition, the number of monitors limits how localized AQI reports can be. “Local conditions can mean that [air quality] is slightly different, or it’s changing,” says Tom Roick, manager of air quality monitoring at the State of Oregon Department of Environmental Quality. People should check outside their own windows to see what’s really happening near them and “keep their very localized conditions in mind when they’re protecting their own health,” he adds.

Those reports get even less accurate when wildfires destroy the monitors. “We know at least one of our monitors might have burned up. Others — the power went out. There are [others] that got overwhelmed with the volume of particulate matter in the air,” says Roick.

When pollution reaches such extreme levels, experts recommend doing everything possible to minimize exposure. “The best way to protect health is to stay indoors and keep indoor air as clean as possible,” says Harris, of the Environmental Defense Fund. During fire season, she uses a HEPA filter in her Northern California home.

Planning ahead is key, Roick says. With climate change exacerbating fire intensity and risk every year, “we can expect this to be happening more and more and it’s kind of a caution to folks to prepare. Having filters handy … having an air purifier is a really good idea.”

Of course, there is another option for some: moving. Going through another California fire season has given Natalie Walsh lots to consider now that she’s back from her backpacking trip. “There’s the psychological part of it. You can’t see the sky. It’s like everything is foggy. You know that it’s not just humidity or water, it’s like toxic. So psychologically that definitely has an impact.” In between checking the AQI, she’s found herself wondering, “What am I doing here? … Do I even want to live in this state anymore?”