AI can’t color old photos accurately. Here’s why

For historians, recoloring an old photograph is meticulous, time-consuming work that computer programs can’t match

Niko McCarty • January 13, 2021

Billie Holiday with her dog, Mister. New York, ca. 1946. Colorized version by DeOldify (top) compared to original black and white (bottom). [Credit: Bill Gottlieb, Library of Congress | CC0 Public Domain]

Jordan Lloyd sees historical, black-and-white photos as a blank slate of pixels — a canvas with colorful potential. But finding the right colors to add to a grayscale image is an intensive process, demanding thousands of Google searches, archival records and phone calls with experts. Sometimes, there’s no way to know for sure if he’s found a picture’s true colors.

For Lloyd, who calls himself a visual historian and sells his services to publishers and private clients, getting the colors right in an old photograph is a moral imperative. Computer programs that offer to do the same job don’t meet his high standards.

“I remember for the D-Day Commemoration, I released an image that I colorized of the D-Day landings,” says Lloyd. “The History Channel showed the same image that had been auto-colorized and it looked terrible.”

Many artificial intelligence tools — computer programs that learn and adapt without human intervention — are taking aim at Lloyd’s profession. With names like DeOldify, DeepAI and Algorithmia, they can color a black-and-white photo in just a few seconds. Lloyd, on the other hand, often spends dozens of hours on each image.

A photo of New York three ways; black and white (left), colorized with DeOldify (middle), and the original photo (right). [Credit: Richard van Liessum | CC0]

Despite the competition, Lloyd probably doesn’t have much to worry about. Computer programs can get a lot of things wrong; they have colored white waterfalls a putrid brown and digitally coated the Golden Gate Bridge with white paint. For the computer scientists behind these AI programs, it’s often difficult to understand why these mistakes happen.

“It’s a black box,” says Jason Antic, co-founder of DeOldify. “[The AI is] picking up on whatever rules it can from the data.”

The DeOldify program — marketed as the “world’s best deep learning technology” for recoloring historical photographs — learned to colorize images by looking at more than a million black-and-white photos that were created from colored originals. Despite the large training set, it still makes mistakes, in part because grayscale images lack crucial data that is present in color images.

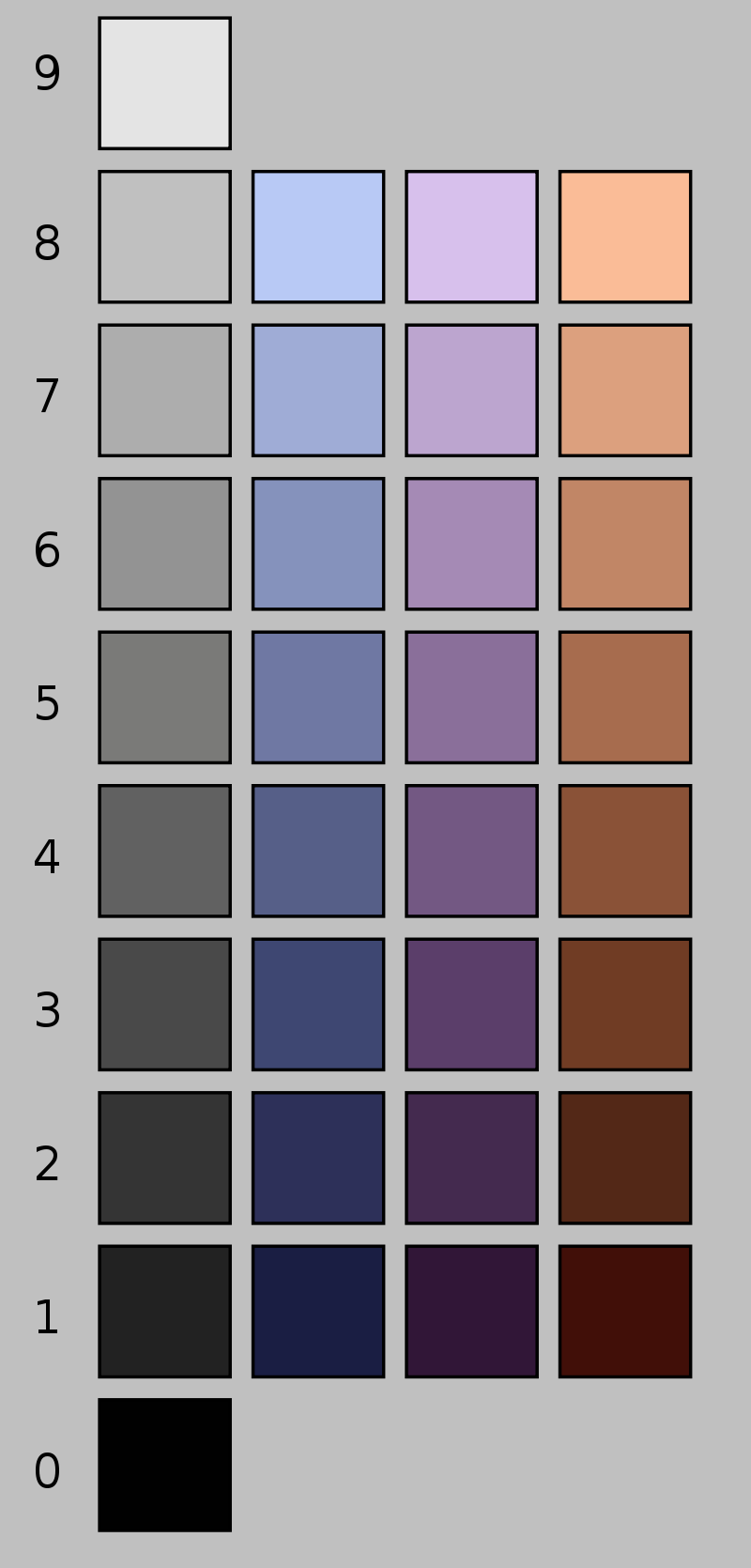

Multiple different colors can have the same lightness value. In this image, 9 is the lightest color and 0 is the darkest color. Shades of grey, in the left column, are compared to shades of blue, purple and orange, all of which can appear the same in grayscale. [Credit: Wikimedia | CC-BY-SA 3.0]

“Colorization is fundamentally ambiguous, as we are going from a 1-D signal (grayscale) to a 3-D signal,” built around mixtures of red, green and blue, says Richard Zhang, who developed auto-colorization algorithms — or colorizers — during his doctorate at UC Berkeley.

Hue, saturation and lightness all contribute to our perception of color, but only lightness is present in grayscale images. That’s part of the reason why recoloring old photos is so hard. Many different colors can have the same lightness value, and thus appear as the same shade of gray in a black-and-white picture even if they are very different in reality.

To create more accurate colorizers, computer scientists have bolstered their algorithms with object recognition software.

“For certain regions [of a photo], we ‘know’ the color with fair certainty. For example, we know that the sky is typically blue, vegetation is green and the mountains are typically brown,” says Zhang. “When there is uncertainty, such as a person’s shirt color, a colorization system must make a guess.”

Antic recently used his DeOldify program, with added object recognition, to recolor an image of a grocery store from the early 1900s. The algorithm colored fruits and vegetables accurately — at least, the bananas are yellow and the apples are red — but it’s impossible to actually know if a “recolorized” photo is correct. The only way to be sure is to find historical evidence, like a text description or a physical artifact, to confirm the colors in a photograph. But Antic doesn’t think that computer programs will be able to interweave historical context in the near future.

A grocery store, ca. early 1900s. The fruits in this image appear to have been colored accurately from a black-and-white original. Colorized image from DeOldify. [Original Image, CC0]

“You’re telling me you’re going to make an AI that can reason what it’s looking at in a scene, then look it up in Wikipedia and correctly identify what’s in the image versus what it’s looking up, and it also has to know what the time and place and context of the image is?” Antic asks. “Good luck with that.”

Other researchers, though, think that something like that may eventually be possible.

“The hard part is creating a machine-learning model to identify motifs in a picture, find relevant historical information and reasoning if the information can be used to color any of the items in a photo,” says Emil Wallner, an expert in machine learning in residence at Google. Wallner thinks that it might be possible to build such a program, but only within a very limited context; maybe a colorization algorithm could recognize shapes in an image and then search a database for items and colors that are often associated with that shape.

For now, though, human historians still have the edge when it comes to colorizing old photos. Through careful research, they can unveil historical details that are missed by machines.

Lloyd has a recent example. While colorizing a famous photograph from 1940 that shows a lone woman walking toward the camera with smokestacks in the distance, he thought he could pinpoint the setting, which had never been identified.

“I’ve managed to not only find the exact location on Google Street View,” Lloyd says, but “I can also confirm the location via elements like trees and telegraph poles, and then show the relative position of the coke plants in the background down to the building positions and chimney stacks from a map produced five years earlier.” Coke is a type of fuel, used to smelt iron ore. Lloyd posted the result on Instagram, showing that the photo was taken on Lawn Street in Pittsburgh.

Those sorts of details — the story behind the photo — make for richer tapestries than what computers can produce. Machines may be able to analyze and rearrange data, but they can’t easily uncover an object’s history.

“That’s the part I’m interested in,” says Lloyd. “Finding the story behind the photograph.”

4 Comments

Good read! A friend has been collects B & W and has been using an app. I taught science for many years so I was curious how this works.

VERY GOOD and useful information, Niko!

One possible way to improve colour accuracy in the result would be to let the user pick some initial starting hues for things like dresses, headgear, furnishings and other inanimate objects in the picture. This could happen at some intermediate point, after the AI program has made a first pass. The program could then tweak and improve on those starting values, even using them to direct the colour-space search for other parts of the picture. This “guided AI” would perform much better than the one that is essentially dumb after it has seen and learned only from all the examples it has been shown.

Thank you for clarifying this. Very interesting article.

Maybe AI could ID the object in a black & white photo, then search for the same object taken with color film to find the proper hues. Example: I have a B&W photo of a 1974 Yamaha dirt bike. AI could ID the year, make and model of the machine, search for color versions of the bike and use those color images to decide how to color the machine in the B&W image.