More than just a weather forecast

Meteorologists are starting to talk about climate change

Delger Erdenesanaa • January 6, 2021

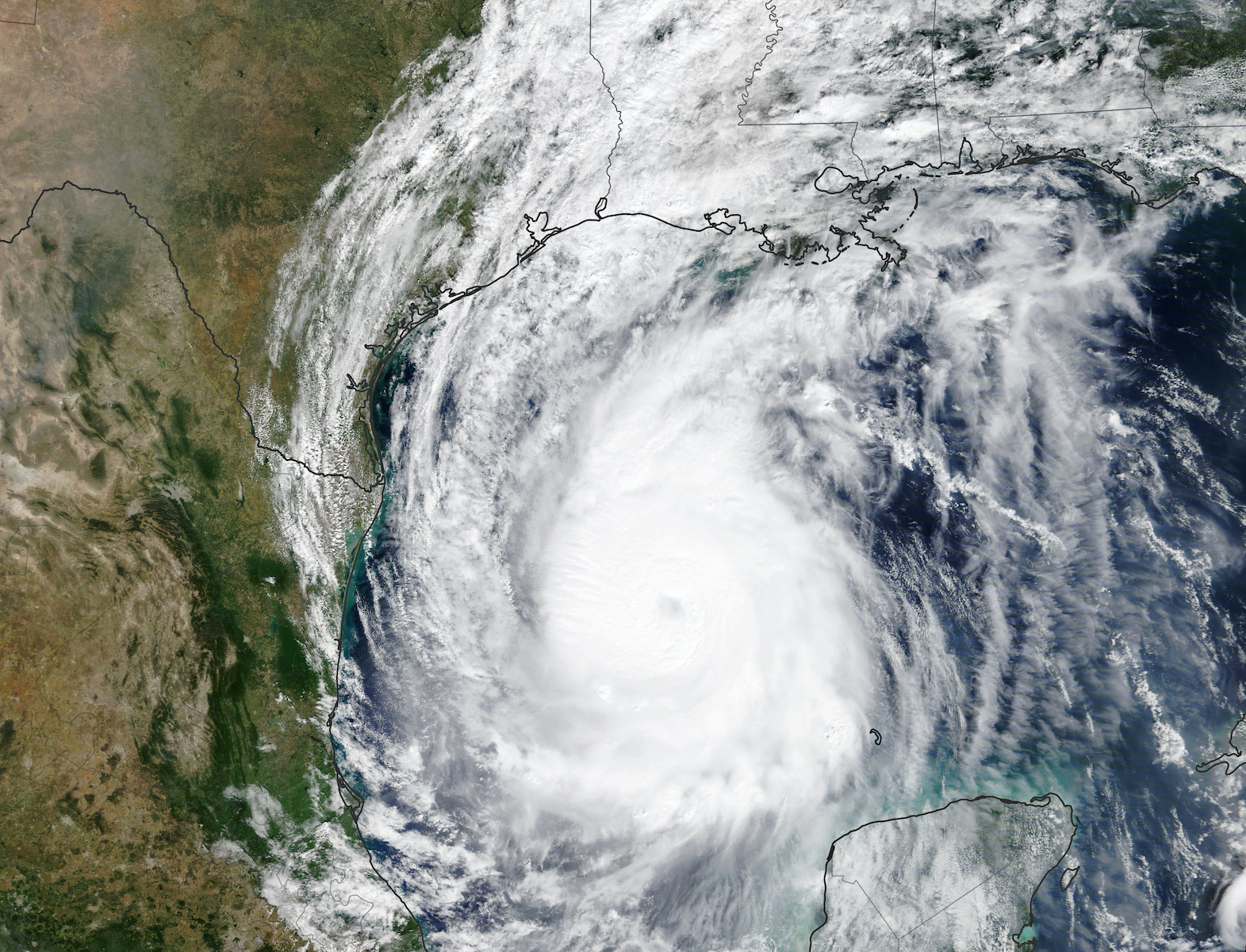

Hurricane Delta approaching the Gulf Coast in October 2020. [Credit: Visible Earth/NASA]

2020 was another record-breaking year of storms and wildfires in the United States. Against the backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic, reports of fiery skies above California and “unsurvivable” storm surges in Louisiana can feel like apocalyptic icing on a hellish cake.

So how do meteorologists decide what to say about extreme weather? And as the climate changes, are weather reports changing too?

TV weathercasters are trusted messengers for many American families — including Casey Crownhart’s family in Birmingham, Alabama. Her state often experiences hurricanes and tornadoes, and the local weatherman is something of a celebrity. But the job is far from simple.

In this Scienceline audio story, climate scientist Jennifer Francis, weather reporter Andrew Freedman and TV meteorologist-turned-advocate Bernadette Woods-Placky tell Scienceline how they think about — and talk about — weather and its connections to climate change.

Music by Jahzzar, Scott Joplin, Komiku and Caffeine Creek Band.

You can also listen to this episode of the Scienceline podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or Stitcher.

(Piano music) Casey Crownhart: Anytime that you would turn on the TV and James Spann had his suspenders on, you’re like, “Oh!” (Piano stops suddenly) Casey Crownhart: This is, this is real. We need to get down into the storm shelter. (Piano music returns in background) Delger Erdenesanaa: That’s my friend, Casey. She’s from Birmingham, Alabama and she loves her local weatherman. (Piano fades out) Casey Crownhart: I don’t know how familiar you are with, you know, weather in the southeast, but Alabama in particular is really prone to, especially, hurricanes and tornadoes. And James Spann is our local weatherman. He’s been on ABC for years and years and years. So just a lot of these really scary moments, you would have James Spann on in the background. You know, you’re listening to him to know whether you should go hide in your basement yet or not. News clip from ABC 33/40: “This is gonna be one of these red letter days. We’re just going to sit back, take a deep breath, and we’ll get through this thing together. But again, Hamilton take cover.” Delger Erdenesanaa: Last year, the U.S. had a lot of extreme weather. As a result, we also had a lot of pretty unusual weather reports. News clip from KIII 3: “2020 outdoing itself once again, with this year’s hurricane season breaking numerous records. Including something we’ve only seen once before — reaching the end of the named list.” News clip from ABC News: “There has been catastrophic damage across the Western United States. And tonight, at least 70 fires are burning in 10 states with no end in sight.” Delger Erdenesanaa: Scientists like Jennifer Francis at the Woodwell Climate Research Center see a link between climate change and these more frequent, more intense storms and fires. Jennifer Francis: The very active hurricane season and the record-breaking fire season out West are both connected to climate change very directly. The ocean temperatures out in the Atlantic were well above normal this year. When we have really warm water out there, that’s one of the main factors that goes into creating a very active hurricane season. Delger Erdenesanaa: But the average American doesn’t get their weather report from a scientist like Jennifer. They get the weather from someone like Andrew Freedman, who’s the Deputy Weather Editor for the Washington Post. I talked to him while he was tracking Hurricane Delta in early October. Andrew Freedman: It’s just a lot of deja vu, because it is headed for the same region in Louisiana that so many other storms have targeted, primarily Hurricane Laura. Delger Erdenesanaa: When Andrew and his colleagues at newspapers and TV stations around the country report the weather, they have to choose their words carefully. News clip from Weather Channel: “Unfortunately, there are going to be some places that get more than 6 feet… how about 9 feet of storm surge, and even more than that? This is not survivable. This is why you need to evacuate when told to do so.” Andrew Freedman: So we heard the “unsurvivable” language. We echoed it, because we thought that the threat was justified and that we’re not in a position to start prominently questioning experts at the Hurricane Center, unless you know, something goes horribly awry… and it turns out that really that storm did break an unsurvivable storm surge. Delger Erdenesanaa: Andrew thinks meteorologists are right to use extreme language like “unsurvivable” to describe extreme weather. He also says meteorologists should talk about extreme weather events in the context of climate change. (Guitar music in background) Delger Erdenesanaa: Why is this important? TV meteorologists have a bit of a reputation for shying away from talk about climate change, and for questioning or even denying the science. My friend Casey’s weatherman, James Spann, doesn’t talk about climate change on the air. In 2018, he told Vice News that although he believes the climate is changing, he thinks nature plays a bigger role than humans. But times are changing. There’s now a growing movement among meteorologists to explain the link between weather and climate change during their reports. (Guitar music fades out) Bernadette Woods-Placky: My name is Bernadette Woods-Placky, chief meteorologist at Climate Central. Delger Erdenesanaa: Bernadette directs a program called Climate Matters, which works with TV meteorologists to talk more about climate change. A survey they conducted this year shows that 95% of TV weathercasters do think climate change is happening. 82% think human activity is a major cause. And more than half say they’ve shared information about climate change on air. Most of these numbers have gone up since the last survey, in 2017. In some ways, Bernadette herself is a case in point. Bernadette Woods-Placky: Climate change didn’t factor into my broadcasting as much as it probably should have while I was on air. This was about eight years ago. I don’t think I understood the science enough to really dig into it. Delger Erdenesanaa: So why does all this matter? If a meteorologist forecasts a big storm accurately, does it make a difference whether or not they link that extreme weather to climate change? Bernadette pointed out that meteorologists are in a unique position. They’re trusted messengers who can talk to people about these changes to our planet. Bernadette Woods-Placky: It is pretty interesting how much of society has that connection with someone they grew up watching, or that they turn on when they hear about a landfalling storm. Delger Erdenesanaa: This personal connection is something that my friend Casey knows all about. Casey Crownhart: We would always have the news on listening to, you know, “Where’s the next tornado watch? Where’s the next tornado warning? When is the hurricane going to fall?” And my dad would always, whenever it got close enough or bad enough, he would take us down. We had like this cement room in the basement… (Sound of rain in background) Casey Crownhart: But my mom would always go on the front porch. And she loved to watch the storm. (Sound of door opening, louder rain, thunder) Casey Crownhart: And we would all be huddled in the basement as soon as the weatherman said so. But (laughs) it just made me laugh to think about that. (Guitar music in background) Delger Erdenesanaa: For Scienceline, I’m Delger Erdenesanaa. (Guitar music fades out)