Long Island’s scallops are dying out. Scientists are hunting for answers.

Unless researchers can pull off a genetic rescue, the triple-whammy of warmer temperatures, oxygen-starved waters and a newly discovered parasite may soon obliterate the few survivors

Lori Youmshajekian • August 14, 2023

Long Island is one of the final bastions of commercially viable scallop populations in the U.S., but the shellfish are now in dire straits. [Credit: Lori Youmshajekian]

From the surface, the serene waters of Peconic Bay don’t betray any hint of the turmoil below. But for Peter Wenczel, who has been dredging and sorting scallops between the north and south forks of Long Island for four decades, today’s haul is yet another disappointment.

“The dead ones sound different,” he explains, picking up a palm-sized shell from the pile and throwing it onto a wooden plank. It lands with a hollow sound. “Once you’ve handled enough, you know they have a certain weight when they’re alive.”

Wenczel’s longtime friend and Cornell University shellfish researcher, Stephen Tettelbach, is also aboard for the scalloping sojourn. He points out another dead giveaway: Look carefully at where the shell gapes at the hinge. If you can’t see a glint of blue, that’s bad news. “Those are some of the eyes, that’s how you know it’s alive,” Tettelbach says.

Scientists suspect this incomplete seal, where the scallop’s eyes stare back at you, makes the creature less hardy than their oyster or mussel cousins. [Credit: Lori Youmshajekian]

Both men have been at this for decades. They’re rugged from head to toe, clad in orange and gray fishing bibs and blue insulated gloves to keep out the cold and the wet. Dredging for scallops is a wintertime endeavor, and the frigid February air makes it an especially arduous task. “Normally, there’s dozens of guys going even this late in the season,” Wenczel says. Now, his boat is the only one on the water apart from the Coast Guard’s — but it’s not because of the weather. It’s because there’s nothing left to harvest.

The elusive catch is the northeastern bay scallop. February is the tail-end of scallop season, which runs from November to March each year in New York. A decade ago, Wenczel would pull in 30 pounds of scallop meat per day this time of year. Now, it’s closer to 15 pounds on a good day. The scallops spawn as usual in the summer but are almost all dead by fall, right before harvest season. This is the fourth year in a row that the fishery has been devastated. Almost 95% of the adult population that spawns at the start of the season is wiped out as November nears.

Why? Scientists have unearthed a trifecta of reasons behind the die-off, with climate change and a mysterious parasite playing key roles.

The northeastern bay scallop looks exactly like an ordinary beach shell: a rounded edge, a corrugated surface and a gently curving contour that tapers into a straight-edged hinge at the base. Most of the scallops in the Peconic Bay are a sooty gray, but genetic variability punctuates some with distinct white lines running parallel to its telltale crinkle, or in other cases tinges its surface with a mélange of white and a dusty orange.

They’re tasty, too. There are dozens of scallop species, but the one that calls Peconic Bay home, Argopecten irradians, is particularly prized for its sweet, buttery flavor. At the Fulton Fish Market and other wholesalers, these Peconic Gold scallops sell for $40 per pound.

In the water, they are funny little creatures. The palm-sized shellfish can hoist themselves away from predators by clapping together their two shells — or valves — and go up into a water column to be carried away by a tidal current, before abruptly settling on the seabed. Its two valves remain sealed shut most of the time except for a miniscule opening at the hinge, where a handful of vivid blue eyes stare out into the world waiting for the signal to flee. But their perception is slow, and they’re unlikely to spot an oncoming enemy, like a fisherman’s dredge.

Symptoms of a dying fishery

With adept hands, Wenczel tosses the rusty steel dredge into the water and pulls on the rope affixed to its long, metal frame to guide its path. The interlocking rings of the dredge function as a net, collecting the bottom-dwelling inhabitants of the bay. After drifting along at one to two knots for a few minutes, Wenczel lugs the dredge back up from the depths manually, pulling firmly on the rope until the steel rings emerge from the depths. He hoists the catch up onto a wooden plank clamped onto the side of the boat and dumps the contents.

A handful of shells tumble out, along with a tangle of slimy, moss-green “slip gut” — evocative slang for a kind of decaying underwater “snot” that sprouts on the seafloor and clogs up baymen’s dredges in the winter.

“In a decent year, you’d pull that dredge up and it would be full,” Wenczel says, pointing at the modest yield. “With scallops and nothing else, not all this sloppy stuff.” He picks up an acrylic board with a square cut out on the long edge and measures one of the scallops against the square. The shell doesn’t touch the edges, which means it’s a bug: a juvenile too small and too young to keep.

“I think these are all bugs,” he says to Tettelbach.

“Put them back?” Tettelbach asks. “Yeah, put them back,” Wenczel replies. “What are we going to do with them?” The two men look over the pile again, checking for adults, then brush away the discarded shells overboard.

In New York, it’s illegal to harvest a scallop younger than a year old or smaller than two and a quarter inches from the hinge to the top of the shell. Adults are identifiable by a raised growth ring: a distinct line that crosses the corrugated grooves of the shell, showing that the scallop had another growth spurt after its first winter.

Scallops can only be harvested from the first Monday of November to the end of March. The restrictions are designed to give scallops enough time to reproduce. “They have one big spawn, and they reproduce throughout the year, too. We don’t want to compromise reproductive potential by harvesting early,” Wenczel explains. “Additionally, they grow like crazy in the spring and fall.” The bigger the scallop, the better for business.

But these juveniles likely won’t last until harvest, and researchers like Tettelbach are still trying to work out how to prevent the fishery’s total collapse.

Trial and error

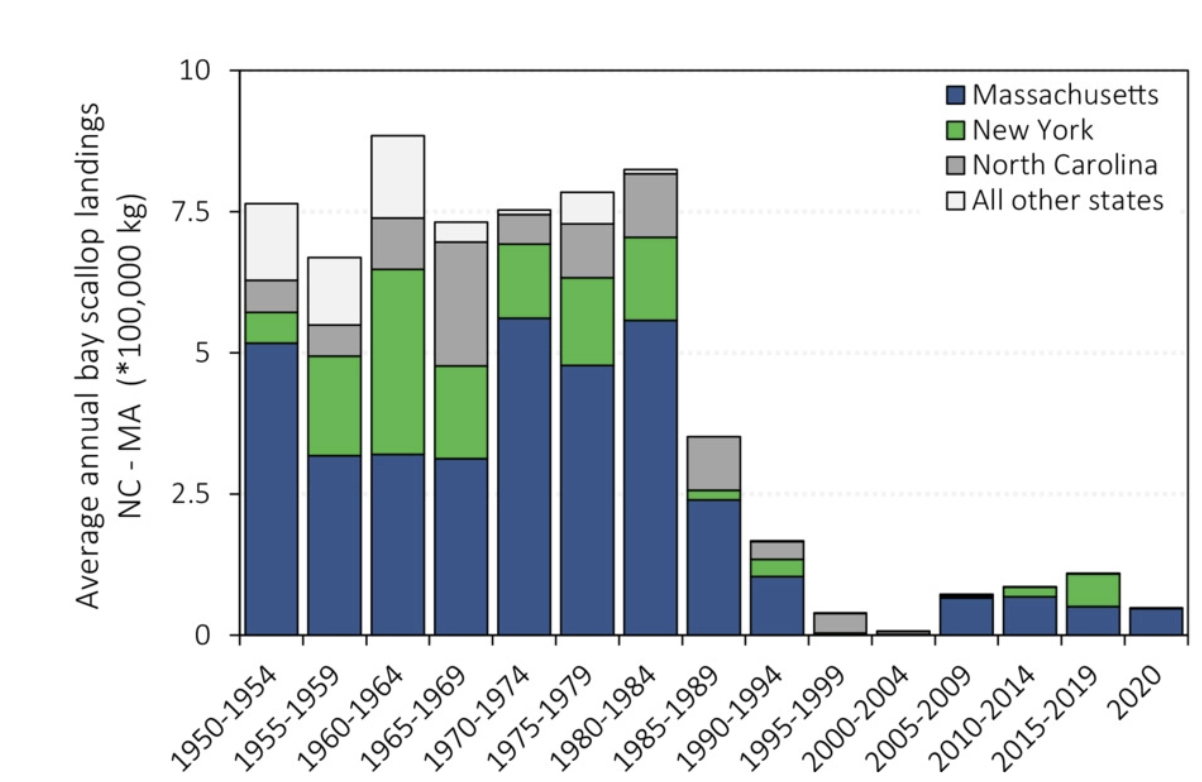

This isn’t the first time the Long Island scallop population has been pushed close to extinction. As early as the late 1980s, the shellfish were in trouble. A series of deadly brown tides — a high concentration of microalgae that takes up all the oxygen — choked most of the population for several years in a row. The tiny algae interrupt the filter-feeding mechanisms of the scallops and effectively starve them to death.

Since 2019, almost none of the bay scallops in Long Island have reached a harvest-ready age. [Credit: Tettelbach et al.]

The last brown tide was in 1995, but the population never fully recovered. For about a decade, there weren’t enough local scallops to repopulate the bay on their own. So, in 2005, Tettelbach and his colleagues planted more than a million scallop seeds in different pockets of the bay.

“We stuffed them in nets really close together,” Tettelbach says. “The idea was that when they reproduced, the eggs and sperm would be released in the same place — it just jump-started the population.”

Then, as soon as the scallops finally started to make a convincing recovery, catastrophe struck again. This time, after a promising spawn in the summer of 2019, another mass die-off wiped out almost all of the adult scallops.

Tettelbach got the call when he was up in Nantucket. “Crestfallen is a word that comes to mind,” he says. “We were crushed.” The 2018 harvest had been the strongest since 1994. “They were going great, then all of a sudden it crashed, like POW,” he says, lifting his arms in the air. “We couldn’t believe it.”

Tettelbach likens the scallops to a canary in a coal mine because of their relatively high sensitivity to environmental stressors compared to the other shellfish in Peconic Bay. [Credit: Lori Youmshajekian]

At first, Tettelbach and a team of other investigators thought an unknown predator could be to blame. The prime suspects were cownose rays, opportunistic feeders that scavenge shellfish buried on the seafloor and were spotted lurking in some of the estuaries in New York. But there wasn’t conclusive evidence to suggest the rays were coming in much larger numbers. So, the researchers instead began investigating water temperatures. The results were stark.

Finding clues

Stephen Tomasetti, then a doctoral student at Stony Brook University, was one of the first to notice something was wrong with the temperature readings. He looked at the historical summer temperatures in the Peconic Estuary and found an increase of 1.25 degrees Celsius from 2003 to 2020. In one area Tomasetti analyzed, Flanders Bay, the scallops were exposed to an eight-day heatwave in 2020. By the end of it, all the scallops were dead. To confirm his findings, he recreated the experiment in his lab. In the same conditions, all the scallops perished within 72 hours.

It wasn’t a total surprise that mass mortality was related to hotter temperatures. Long Island’s formerly thriving lobster fishery was devastated by warming water in 1999. Similarly, mass temperature-related die-offs have also been reported in blue mussels around Delaware Bay and cod in Maine.

But temperature isn’t the only factor at play. Peconic Bay scallops must also now cope with water that is extremely low in dissolved oxygen. These hypoxic conditions are severely stressing the scallops, according to Tomasetti’s research.

Tomasetti monitored the heart rates of scallops in the Peconic Bay to find out how stressed they were. Like humans, the more the stress, the faster the heartbeat.

“It basically tells me about how rapidly they’re expending their energy,” he says. “If they’re depleting their energy reserves rapidly for a sustained amount of time, we would say that they’re under stress.” Under sustained stress, the scallops’ entire internal system begins to shut down — a precursor to death.

What the scallop heartbeats couldn’t reveal, though, was a third factor: a widespread parasite afflicting the entire scallop population at Peconic Bay.

Seeking solutions

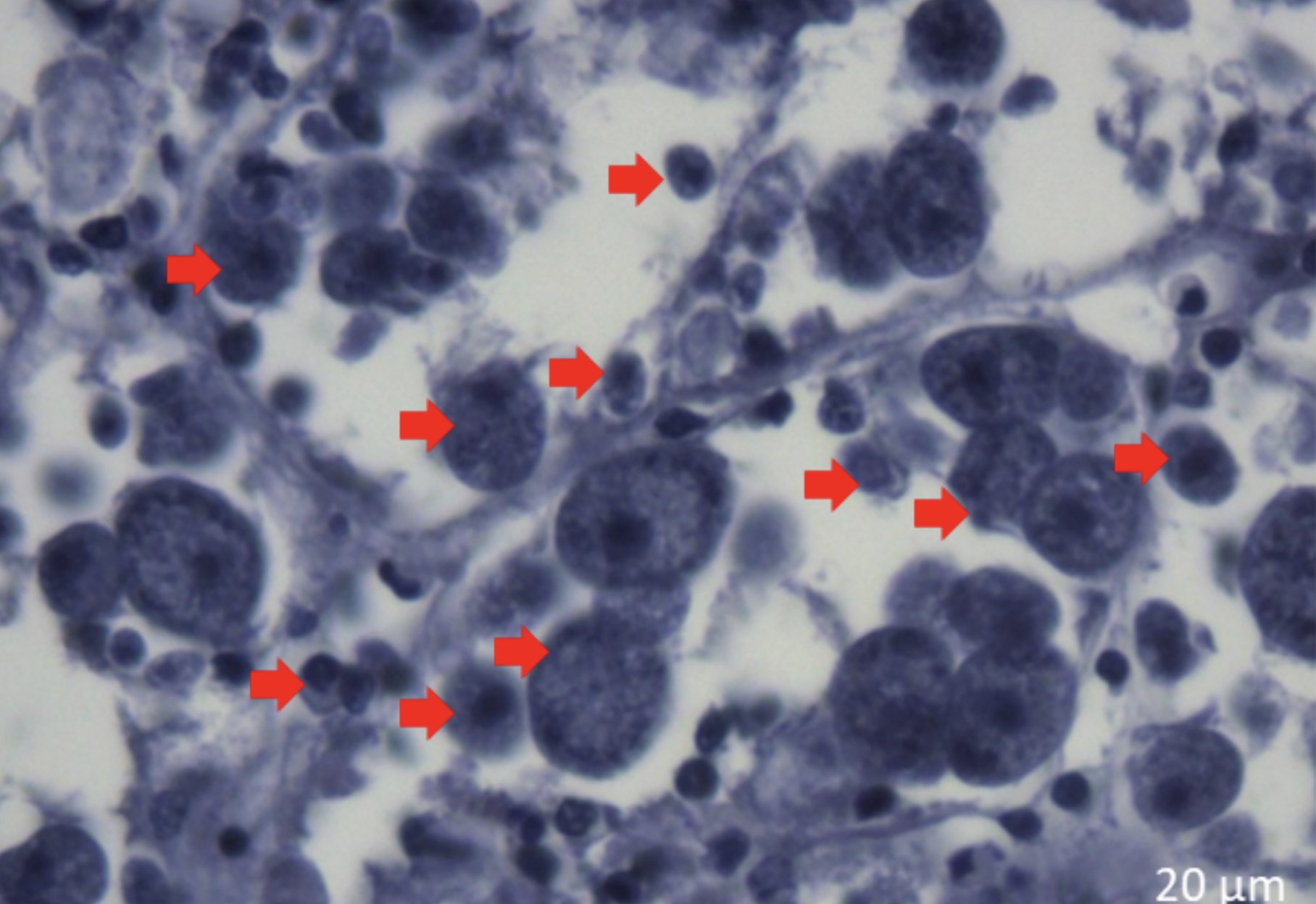

Among those tasked with solving the scallop mystery is Bassem Allam, who studies the pathology and immunology of marine invertebrates at Stony Brook University. In 2020, just as Tomasetti was following temperature patterns, Allam discovered something disturbing under the microscope. A tiny, oval-shaped and previously unknown parasite had completely colonized a scallop’s kidney. The takeover was so extensive that Allam couldn’t even see any kidney cells.

The parasite cells have a telltale dark spot in the center, making them easy to spot under a microscope. [Credit: Bassam Allam]

“The extent of the infections is really out of control,” Allam says. “You have heavily infected scallops, and then summer comes, so it adds stress on stress and they really don’t do well.”

He found that virtually all of the scallops in the bay were infected to varying degrees. As far as the researchers know, there’s no threat to human health by eating the infected shellfish, but the scallops themselves aren’t so lucky.

Allam thinks the parasite is the main culprit, crossing a stress threshold that the scallop could no longer tolerate.

“We had severe temperatures in the past. We had dissolved oxygen in the past. There were no reports of die-offs,” Allam says.

Tettelbach agrees that the parasite has been a critical factor. But, he notes, “the parasite was probably here before 2019, which was the first year of the die-off, so we need to ask: Why did it happen in 2019?”

The researchers’ efforts are now focused on shoring up the surviving scallop population and selectively breeding them. Since scallops only live for two years, Tettelbach and his colleague, Harrison Tobi, an aquaculture specialist at the Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County, have gone looking for adults that have survived the deadly trifecta: the parasite, the heatwaves and the low oxygen levels. They collected those rare two-year-olds during multiple dives in spring last year to use as parent stock for a spawn. Now, those one-year-old scallops that spawned last year are being deployed at sites across the Peconic Bay.

“We hope they survived because of genetics and not just chance, so that those genetics can be passed down,” Tobi says.

It’s a strategy that has worked well with the area’s oysters and clams, so there’s good reason to believe it should work with the scallops, Tettlebach says. “But to what degree that might improve population levels and ultimately how many survive to harvest season is unknown at this point,” Tettelbach says.

Tobi is part of a team monitoring the scallops this summer to see whether any of them exhibit lower parasite levels as well as higher survival rates. Those tenacious scallops will then be used in future spawns so that the population builds resilience.

Yet another twist is that, according to early findings by Allam’s team, disease levels differ between the two subspecies of Peconic scallops in the northern bay and the southern bay.

In his quest to understand how and why the genetics of Peconic scallops have diverged into two subspecies, Allam’s lab has procured historical samples from the Museum of Natural History and plans to do a genomic analysis on them.

But while uncovering the scallops’ genetics may be their best long-term hope, it may take years to bear fruit. For now, it’s a bleak outlook for Wenczel and his fellow baymen who fear another winter of scant income.

“Without scallops around here, there’s really nothing going on in the winter,” he says.

Even so, Wenczel remains hopeful the tides will turn. “They always come back,” he says. “When there were no scallops during the brown tide years, they came back.”

Editor’s note (August 17, 2023): This story has been updated to clarify the timing of spawning efforts.

3 Comments

Thank you for this news, I would like to keep abreast of the scallop challenges!

I read this article and know what is meant by this article, I have read a lot of articles, maybe this is a good one in my opinion. I’ll spread this to my friends. Thanks. “OnicPlay“

this information is very god