Could AI be your next radiologist?

New research suggests artificial intelligence detects more breast cancer cases than two radiologists

Sara Hashemi • November 3, 2023

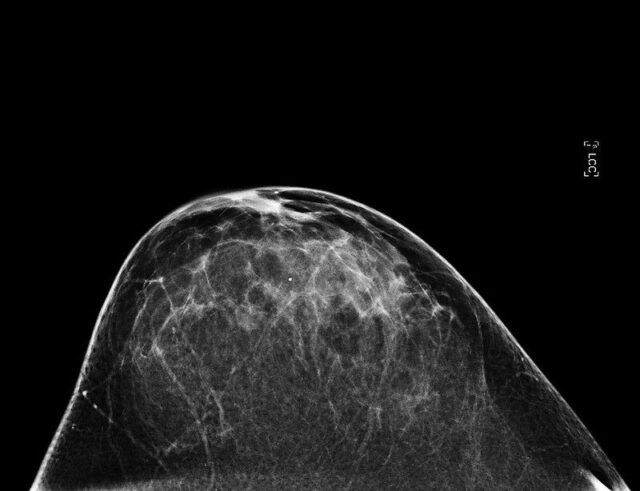

AI algorithms can scan mammogram images like this one for signs of breast cancer. [Credit: National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health | CC BY-NC 2.0.]

Artificial intelligence can already generate weird images, write the lyrics to a catchy song and help create new recipes. Now, it’s adding a new role to its ever-expanding resume: detecting cancer in mammograms.

More than 55,500 Swedish women participated in a study examining the effectiveness of AI in mammography. The researchers found that the current European approach of having two radiologists read every mammogram catches 4% fewer cancers — and generates more false positives — than a single radiologist working with an AI tool known as Insight MMG. And although AI alone isn’t quite as effective as a human-AI pairing, it was as accurate as two radiologists.

“We were very surprised that AI alone found the same amount of cancers,” says Dr. Karin Dembrower, a breast radiologist at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm and the lead author of the study.

These findings suggest that using AI could not only lead to better health outcomes for patients, but it could also help ease the global radiologist shortage, Dembrower said. The current number of radiologists — many of whom are leaving the field because of burnout and the impact of COVID-19 — can’t meet the demands of an aging population. This could in turn free up physicians to focus on what they do best while sharing some other duties with a new generation of sophisticated AI tools.

But this doesn’t mean AI is ready to take over just yet. The study’s findings need to be confirmed by other large trials, especially ones that also assess long-term outcomes. The women in the study were tested at a single hospital and were not categorized based on race or ethnicity, so it’s unclear if the outcomes would be different for more diverse populations. And the study was partially funded by Lunit, the South Korean company that developed Insight MMG.

While more studies are needed to address all those uncertainties, these results are still exciting, says Dr. Laura Heacock, a breast radiologist at New York University Langone Health who was not involved in the Stockholm study. “All we want at the end of the day is to give better care to our patients, find more cancers, be able to intervene earlier, offer them treatment at earlier stages,” Heacock says. AI, she adds, “is a brand-new tool for us, and it’s very exciting that we have it.”

The study was designed to test how AI performs compared to the way mammograms are analyzed in Sweden and many other European countries. Typically, two radiologists independently assess a patient’s mammogram, and if either finds something suspicious, the clinicians will discuss the images. The Swedish researchers compared the accuracy of three groups in analyzing mammograms: two radiologists working independently, one radiologist plus the AI program and AI on its own.

“The results were fantastic,” says Dembrower. “We could show that replacing one radiologist with AI will detect more cancers and will recall less women.” (A recall is a false positive result in which a patient’s mammogram is wrongly considered abnormal, leading to unnecessary follow-ups.) Relying on one radiologist with AI led to a 4% decrease in false positives. And the AI working alone cut the number of false positives by half because there is less human error.

Cutting down on false positives reduces patient anxiety and unnecessary biopsies, Dembrower says. The researchers also learned that the AI and radiologists tended to notice different things on mammograms, so working together increased the chances of detecting cancer.

Lunit’s AI algorithm is a deep learning model trained on five datasets from South Korea, the U.K. and the U.S. The AI analyzes a range of other data in addition to mammogram images, including the patient’s age and different details about the exam such as the compression force or type of radiation. It then outputs a risk score for signs of a tumor in the image.

Insight MMG isn’t the only AI that can help with cancer screenings. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has already approved over 500 artificial intelligence and machine learning medical devices for radiology, and that number keeps growing. NYU Langone Health and a few other large private practice groups have already started using AI to assist with mammogram readings, Heacock says, but there isn’t any publicly available data on how many institutions have started using these tools.

Dembower hopes future studies will compare the accuracy of various AI tools and include more diverse populations at more than one hospital. A larger trial is already underway in Sweden, with promising preliminary results recently published in Lancet Oncology. The researchers screened over 80,000 patients at four different sites in the country and concluded that AI-supported screening works as well as two radiologists.

A key uncertainty is whether AI will perform as effectively in improving patients’ health outcomes over the long run, not just in initial diagnoses, says Nehmat Houssami, a breast physician at the University of Sydney in Australia. Dembrower’s team is already planning a follow-up study to address this issue. The researchers will examine cases that were flagged as possible cancers but were later dismissed, as well as so-called interval cases, which are cases diagnosed after a patient initially received a negative mammogram result. Those cases are important because they tend to have a more negative prognosis.

There’s also the question of whether AI will perform this well in the U.S., where populations are more diverse and protocols are different. Only one radiologist looks at images in most U.S. cases, but that doesn’t mean we should assume that AI would be even more effective here. The system is too different from Sweden to make that jump, NYU’s Heacock says, so we need more American studies to support the Stockholm study’s findings. “When we’re looking at studies performed in the United States, we want to make sure that they’re done on a population that reflects the population at [our] hospital,” Heacock adds.

It’s unlikely that AI will completely replace human radiologists any time soon, according to Dembrower and Heacock. There are still few regulations or clear guidelines on the use of AI in health care, so clinicians tend to be cautious. As the technology evolves, Houssami says it will be important to communicate clearly with patients, who need to understand when and how AI will be integrated into their care while also receiving reassurance that humans remain a part of the process.

AI may eventually end up handling most of the initial reading of screening mammograms, while radiologists would work with patients and monitor the performance of AI, according to Dr. Fredrik Strand, one of the researchers on the Stockholm study.

Dembrower’s hospital, Capio Sankt Göran, has been using AI to support mammogram screenings since last summer, and while she says it’s still too early to make a definitive judgment, she’s feeling positive about the process. In addition to more accurate readings, she says, doctors are available for more advanced diagnostics, their workloads have become easier to manage, and waiting times for patients are shorter.

“When we started the study, my colleagues were a bit reluctant to use it,” Dembrower says of the AI. “Now, they don’t want to work without it.”