The truth about those annoying CAPTCHA tests

The tests made to keep bots out of websites aren’t working anymore

Carrie Klein • February 18, 2024

Bots are better at solving CAPTCHAs than humans, according to recent research. [Credit: Carrie Klein]

Select the squares with motorcycles. Decipher the squiggly letters and numbers. Check the box that says “I’m not a robot.”

Prompts like these, called CAPTCHAs, were designed to keep bots from hacking into sites to steal data, create false accounts, deliver malware and more. The problem? They’re not working very well.

While CAPTCHAs have lost none of their capacity to annoy us humans, bots can now figure them out with relative ease. “They’re not actually as effective as everybody wants to think they are,” says Amanda Fennell, who teaches information technology at Tulane University and serves as chief information officer at Prove, a company that verifies the identity of internet users.

So why don’t CAPTCHAs work anymore? And what might come next? I talked to cybersecurity experts to find out.

What is a CAPTCHA anyway?

A CAPTCHA, or Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart, is a modern take on a test first created by English mathematician Alan Turing in 1950 to see if machines could think like humans. If an observer was fooled into thinking a computer’s responses were from a human, the machine was said to have passed the Turing test.

The lengthy acronym was coined in the early 2000s by then-Carnegie Mellon student Luis Von Ahn and his mentor, Manuel Blum. Von Ahn, who later founded DuoLingo, also created reCAPTCHA (the classic “I’m not a robot” checkbox), which was purchased by Google in 2009.

CAPTCHAs were designed to be feasible for humans and difficult for bots. When they were first created, reading obscured letters and numbers was thought to be a uniquely human skill. When bots got good at that, image-based CAPTCHAs were created. But bots can now solve those too.

For humans, on the other hand, poor eyesight and disabilities make these tests frustratingly inaccessible.

“I have very bad vision,” says Fennell. “Every time I see a CAPTCHA, I get my glasses on and I stare at it and I’m like, ‘Am I an android? Does somebody not want to tell me that I’m a machine?’ Because I can’t pass them for the life of me.”

What are the major types of CAPTCHAs?

The simplest CAPTCHA displays a stagnant image, typically of numbers and letters, and asks users to type what they see.

Those “just don’t work anymore,” says Phillip Mak, a professor of cybersecurity at New York University and former cybersecurity lead at the U.S. Department of Defense.

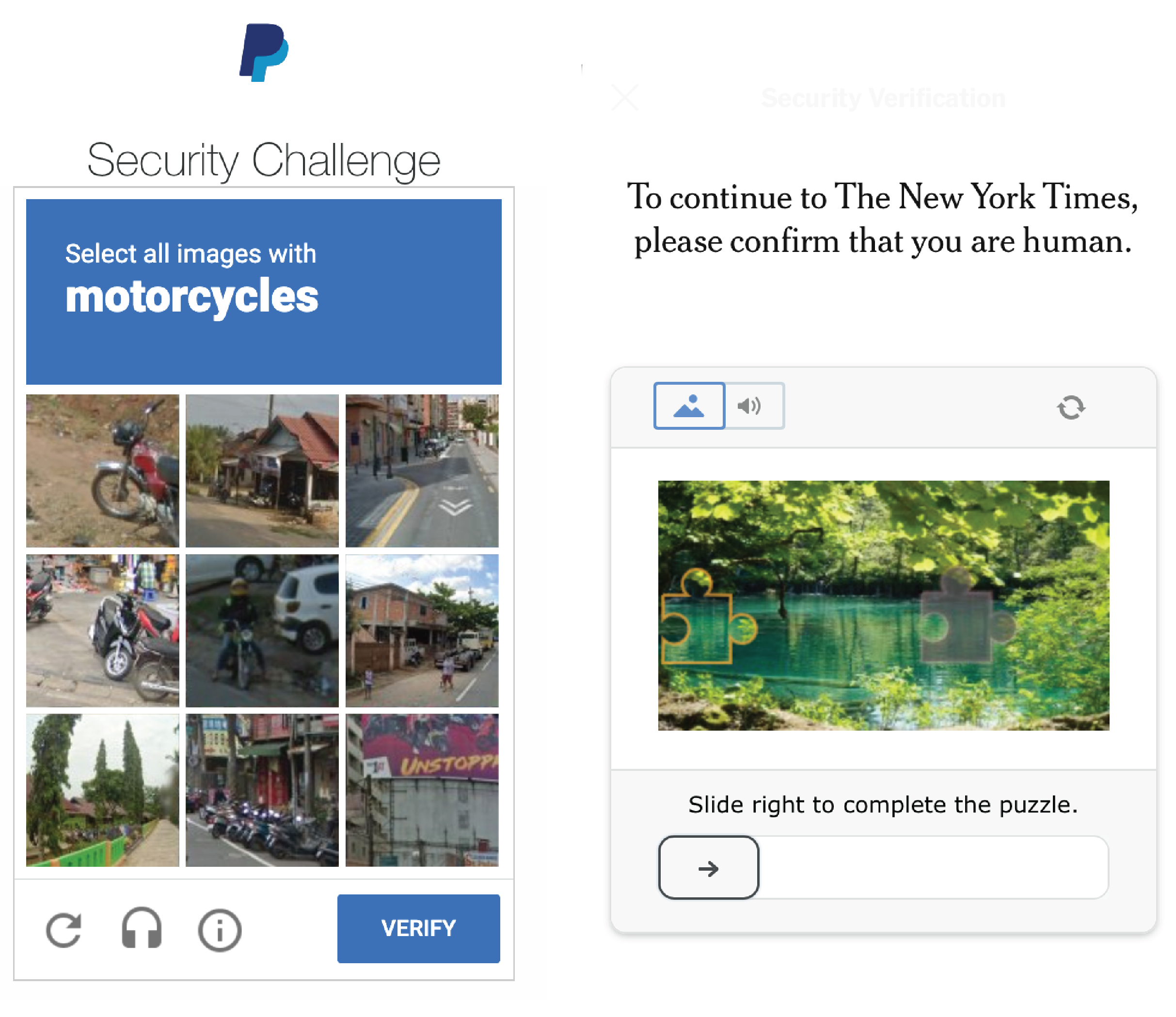

More advanced CAPTCHAs are interactive or gamified, like the ones below that popped up when I was trying to login to PayPal, and later, read The New York Times.

Two types of more complex CAPTCHAs. [Credit: Carrie Klein]

Some CAPTCHAs ask users to rotate an image to the correct upright position.

An interactive CAPTCHA, thought to be more difficult for bots to solve. [Credit: Arkose Labs]

Programming bots to solve CAPTCHAs like these requires a much more complex algorithm, explains Jaskaran Singh Walia, who studies CAPTCHA vulnerabilities. It’s not impossible, he says, but to deploy on a large scale, it would be expensive.

Still, “there’s nothing stopping artificial intelligence from solving” these types of CAPTCHAs, too, Mak says. “I would expect in a couple of months you’ll see AI doing that.”

Why aren’t CAPTCHAs keeping bots out anymore?

Bots have gotten better and better at solving CAPTCHAs over the years, largely due to advances in machine learning and artificial intelligence. OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, reported in March that its latest technology successfully tricked a human into filling out a CAPTCHA for it. The bot messaged a person on the freelance labor site TaskRabbit, claiming to be vision impaired and to need help filling out a form. Then, in a sci-fi-esque role reversal, a human completed a CAPTCHA for a bot.

Bots can already solve most forms of CAPTCHAs at higher success rates than people, according to research from Microsoft and others. Users get CAPTCHAs correct 50-85% of the time, while bots get them right 85-100% of the time.

There are even programs that will solve CAPTCHAs for you, which could be welcome news for users tired of proving their humanity time and time again. One of these is NopeCHA, a chrome extension Singh Walia uses. “I don’t even have to run an algorithm or a model,” Singh Walia says. “All you have to do is add the extension and it just automatically solves the CAPTCHA for you.”

But the easy availability of these programs also means that CAPTCHAs are more vulnerable than ever. “There’s no point in displaying such CAPTCHAs anymore,” Singh Walia says.

Are there alternatives?

“We know that the end is near for CAPTCHAs. They won’t survive much longer,” says Mak, the NYU cybersecurity professor. The next phase of the technology, he explains, will have, “CAPTCHA-like functions performed in the background without any interaction from the user the majority of the time.”

Conveniently, taking the user out of the picture also makes CAPTCHAs more secure, Mak says.

One example of this is called the honeypot technique, where coders place a field in a form that only spam bots can see, Fennel explains. If that field is filled out, it’s clear that a bot is trying to access the site and the form will block bots from continuing.

Another secure technique is a time-based form, which measures how quickly questions are filled out. If a form is completed too fast, it’s likely being done by a bot and the form will automatically kick it off, Fennell says.

What can we do to better protect ourselves from bots?

Here are three three steps to keep your accounts and information secure online:

First, make sure the website you’re visiting is the one you expected to visit. If another window pops up that you didn’t mean to go to, get out of there.

Second, check if the website is legitimate. Most sites will have a lock symbol next to the website URL. If it’s not there, the site may not be verified, Fennel cautions.

Finally, the classic advice you’ve probably heard before is still true: having different and complex passwords for every site you use is essential, Mak says. Two-factor authentication is another way to add a layer of security, which requires two forms of identification to access a site (for example, your password and a code sent to your phone). You can turn this on for sites like Google.

New website security measures are looking promising. “I’m very optimistic about these technologies improving safety, security and accessibility for users,” Mak says.

But keeping bots out is a continually evolving game. “The only thing that’s ever going to change any of this is if we just make people smarter about security,” Fennell says. In the meantime, she adds, bots will keep getting better at solving CAPTCHAs. “That’s why we have to stay evergreen and always try to stay one step ahead and build a better mousetrap.”

1 Comment

This is an interesting topic Carrie Klein! (This comment posted on 2/24/2024). I see that the story was posted on 2/28/2024. I’m wondering how long did it take to research and publish the story?