Cheetahs will soon return to India – but for how long?

Decades after the last Indian cheetah was killed, 36 will soon be imported from Africa. Conservationists aren’t sure it will work

Niranjana Rajalakshmi • August 26, 2022

African cheetahs that are about to be reintroduced to India are almost genetically identical to Asiatic cheetahs, says Yadvendradev Jhala, the director of Project Cheetah. [Credit: James Temple | CC BY 2.0]

Once, there were thousands of wild cheetahs in India. That was before the Maharajas and other wealthy Indians hunted them down for sport, killing the majestic cats or exploiting their docile nature by taming them to assist in organized hunts of gazelles and other games. One Mughal emperor, Akbar, was said to have kept 1,000 cheetahs in his menagerie, capturing as many as 9,000 during his half-century reign in the 16th century.

By the late 1800s, the cheetah was on the verge of disappearing from India. Cheetahs were officially declared extinct in the country in 1952.

But now the world’s fastest cat is sprinting back to the subcontinent. The Indian government in early 2020 approved Project Cheetah, a plan to introduce 36 African cheetahs over the next five years into Kuno National Park, about 300 miles south of New Delhi. The first batch of cheetahs are likely to be arriving this month.

While the introduction plan gives animal lovers an adrenaline rush, some wildlife biologists in India and elsewhere are skeptical. They worry that trying to revive India’s only extinct carnivore may fail, as other large animal reintroductions have elsewhere in the world.

“A group of 36 cheetahs will not be a viable breeding population,” warns Ravi Chellam, a conservation scientist based in Bangalore. He explains that a small group of cheetahs isn’t enough to preserve the species in the long-term, because they won’t have enough genetic variation to grow into a big, successful population. “Wildlife conservation is not akin to collecting stamps,” he says.

The national park selected for the cheetah introduction can accommodate no more than 36 cheetahs, according to the Project Cheetah report. But Chellam, who is also the CEO of the Metastring Foundation, says at least 50 cheetahs will be needed, since they are less diverse genetically.

Yadvendradev Jhala, the project leader, counters that he’s optimistic the reintroduction will not only succeed but will also benefit other plants and animals in its food chain. There is no doubt about its political popularity, too. The mere possibility of reintroducing cheetahs to India 70 years after they were declared extinct has delighted many Indians, who continue to express their excitement on social media platforms.

History suggests their hopes might be dashed, however. Carnivore reintroductions have a mixed record around the world, in part because large animals require so much territory for hunting, according to Jesse Alston, a quantitative ecologist at the University of Wyoming. In a 2019 study, he argued that in most cases there is not enough data to justify reintroducing top predators into ecosystems.

“If you remove a predator, the sort of the prey species will change,” he says. Decades later, if that predator returns, it doesn’t mean that those prey species will return, too.

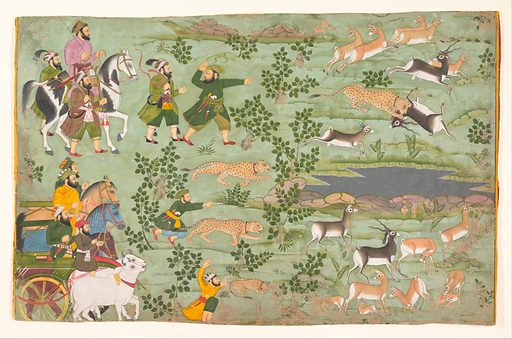

India’s emperors captured cheetahs from jungles and used them for hunting. In this 18th century painting, cheetahs trained by the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan can be seen hunting deer and blackbuck. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In Kenya, for example, the zebra population boomed when lion numbers declined. But when the big cats were restored, they preferred hartebeests to zebras, triggering an imbalance in the ecosystem, according to a 2017 study.

Similarly, a plan to reintroduce red wolves in North Carolina didn’t work out as planned. Coyotes, which thrived in the absence of red wolves, interbred with the arriving wolves, resulting in a hybrid “coywolf” and disrupting red wolves’ genetic integrity — or their ability to remain adapted to their natural environment.

There have been a few successful predator reintroductions, however. One of the best known is the rewilding of gray wolves in Wyoming’s Yellowstone National Park, which helped the ecosystem regain its balance by keeping the overgrazing elk population in check.

Elk are much scarcer in Eastern North America, but a reintroduction effort that started in 2001 also appears to be working. The elk population in the Great Smoky Mountains has grown from just 27 to 200, according to Alston.

Reintroducing a top predator can also help curb the spread of diseases, says Sebastian Di Martino, a big cat expert who recently helped oversee the reintroduction of jaguars into wetland areas of his home nation of Argentina. Predators usually kill animals that are weaker, including those that are afflicted with diseases. He explains: “Eliminating such animals is paramount to curb the spread of diseases to other animals as well as humans.”

In India, the cheetah project is technically an introduction, not a reintroduction, since the plan is to introduce a subspecies of the African cheetah, instead of the Asiatic cheetahs that were native to the Indian subcontinent. There are still small numbers of Asiatic cheetahs in other countries, but too few to risk moving them to India. In Iran, for example, there are just 12 left in the wild.

Fortunately, African cheetahs are almost genetically identical to Asiatic cheetahs, according to project director Jhala, who is also the dean of the Wildlife Institute of India.

“You can take even a skin graft from one subspecies and put it on the other and they will not reject it”, he says.

Cheetah researcher Adrienne Crosier of the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute had high hopes for Project Cheetah, but worries that the introduced African cheetahs will not be able to breed effectively in India. The animals are very sensitive to even the slightest distraction and may have trouble adjusting to life in a crowded national park open to the public, she says.

This skittishness explains why cheetah numbers dwindled during the Mughal period. Though Maharajas captured thousands of cheetahs for hunting animals like blackbuck, the big cats rarely bred successfully in captivity. As a result, Mughal emperors like Shah Jahan continued to trap them in the wild, driving down their numbers.

One of the key justifications for Project Cheetah is as a way to improve the health of grasslands, since deer and other prey animals can overgraze if left unchecked. Healthy grasslands even play a role in slowing global climate change, since they sequester carbon.

But critics say that if the Indian government really wants to help its grasslands, it should be doing much more than just importing a few cheetahs. Dropping the animals into grasslands won’t significantly restore the ecosystem, says Sanjay Gubbi, a leopard expert in Bangalore. He adds that merely planting trees and giving away large chunks of land for development will not lead to conservation. Similarly, just bringing in a few cheetahs will not restore the grasslands.

A better strategy, Gubbi says, would be to focus on recovering critically endangered species like the great Indian bustard, a flagship grassland species of bird, instead of trying to bring back a big cat that has already disappeared. He adds that the bustard was once almost named India’s national bird. “How unlucky would it have been if this bird had been the national symbol now.”

Given that thousands of taxpayers’ dollars are invested in projects like these, Gubbi says it is critical to get the consensus of the larger scientific community. As the mixed track record of past attempts to reintroduce top predators shows, such projects are a roll of the dice, according to Wyoming’s Alston.

“It’s hard to just say that the outcome will only be positive,” he says.

1 Comment

We need to protect this species at all cost. Humans can’t go long alone.