What you don’t know might hurt you

The many shades of gray between thyroid problems and mental illness

Jillian Rose Lim • August 18, 2014

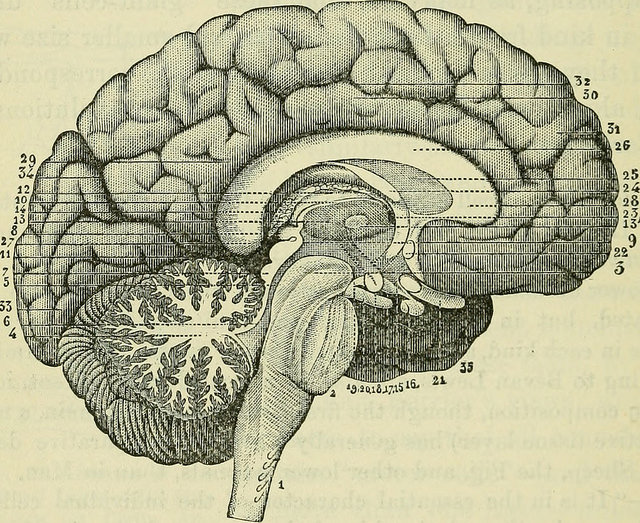

The body and the brain: symptoms of thyroid disease can sometimes masquerade as symptoms of mental illness. [Image credit: Flickr User Internet Archives Book Images]

Last January, Irish journalist Caroline Walsh walked off the Dún Laoghaire pier in an apparent act of suicide. Her husband, James Ryan was shocked. Caroline was an active mother who cycled and jogged. Frequent check-ups and two thyroid exams revealed no signs of any tumor or trauma, cancer or clot. Although she was diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, Caroline took medication and her mood improved. Over Christmas, she planned dinner menus, wrote shopping lists and called friends. “There was nothing to suggest that she was destined, that afternoon, to set out alone on a journey, a journey which ended in St. Vincent’s hospital, where she struggled for life for almost three hours,” James wrote in an Irish Times editorial.

But James knew something about his wife that I now know about myself: it wasn’t just anxiety. Caroline’s vague shifts from healthy and active to shaky and depressed, her bouts of energy and dredges of depression — her state of well but not well — had a physiological root quite separate from the brain. Caroline had hyperthyroidism: a thyroid disorder that went undiagnosed up until a couple of weeks before her death. Even when diagnosed, the thyroid problem seemed harmless, causing only isolated periods of fatigue. At all other times, Caroline was herself.

The thyroid gland sits at the base of the throat where the neck meets the collarbone. It produces hormones called thyroid-stimulating hormones (TSH) that affect every cell in the human body. But you can’t see the thyroid. And thyroid disorder symptoms can masquerade as everyday turbulent emotions (at best) or mental illnesses like depression (at worst). It’s the sort of problem you don’t know you have until you’ve lost something, like all your energy or your mind.

Researchers from the Erasmus Medical Center in the Netherlands recently published a study that links normal but low thyroid hormone levels with high rates of depression in elderly people. “These results show that even minor variation in thyroid function within the normal range can have important effects on affective behavior,” the authors write. They urged that people who felt even the slightest depression get their thyroid tested, because a small variation in hormone levels could cause depression, which thyroid medicine would likely alleviate. The research contributes to a body of evidence that dysfunctional thyroids can create symptoms that mimic anxiety or depression. And though still debated, the majority of doctors believe patients who feel anxiety, fatigue or depression should have a thyroid test before writing the issue off as a casual problem or a need for antidepressants.

About 59 million Americans have a thyroid problem, but 60 percent of them don’t know about their condition, the American Thyroid Association reports. In the book Unmasking Psychological Symptoms, Harvard psychiatrist Barbara Schildkrout lists 100 other medical disorders that masquerade as mental illnesses. Among them are lupus, Lyme disease and diabetes. “Sometimes these physical illnesses are capable of persisting for years without worsening dramatically and without evolving into a crisis that would make it clear an underlying organic disease is present,” writes Schildkrout.

Dr. Alice Cheng, an endocrinologist at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto admits that many patients who arrive at her office experienced symptoms for a long time — [months or even years] — before they were diagnosed. “This was usually not due to misdiagnosis by the health care team but rather a delay in the person presenting to their family doctor,” says Dr. Cheng. “The person thought that his or her symptoms were just due to lack of sleep or anxiety.”

Cheng explains that the symptoms of thyroid disorders are so nonspecific and vague—fatigue, dry skin, anxiety—that it’s easy to assume they are normal. “There are many things that cause the same symptoms and everyone has some of those symptoms, some of the times,” she says. “Thyroid hormone plays a role in almost every bodily function including mood, thinking and emotions. When there is either too much or too little thyroid hormone, these aspects do not function normally.” Cheng says that hyperthyroidism (too much hormone) can create anxiety, agitation and forms of mania, while hypothyroidism (not enough thyroid hormone) can create depression, slower thinking and fatigue. “Of note, many of the symptoms of hypothyroidism and depression overlap, further adding to the confusion,” she says.

Such was the case of Caroline Walsh, whose symptoms spiraled at a quick speed towards a dark end. Her suicide highlights several issues surrounding the diagnosis of a thyroid disorder: how can one distinguish between thyroid dysfunction and mental illness? Or between thyroid dysfunction and just a mood swing? When are thyroid levels low enough to be treated, and how can people find out if they are at risk? If 60 percent of Americans with thyroid disorders don’t know about their condition, does some part of that percentage suffer from mental health problems anyway?

“If I were to fix on one point of information which would, in the course of those weeks have been of real value, then it is the now seemingly established view that there is no known correlation between the extent of hyperthyroidism and psychiatric symptoms that subsequently develop,” writes Ryan James in the Irish Times. “In other words, given the nature of Caroline’s death and the paucity of knowledge in general about the condition, it was assumed by many that she had a history of depression.” James says the problem with cases like Caroline’s is that one must be tested early for thyroid disorders so as not to hinder treatment for its effects, especially when “there is a physiological basis to a psychiatric condition.”

Dr. Cheng advises people to go in for the “only reliable objective tests” available for the thyroid — a TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone) blood test. Cheng says people should ask themselves whether or not their TSH has been done recently, and have a check-up if it’s been a while. Dr. Russell Joffe, a psychiatrist at the North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System, agrees. “If someone comes in with depression, the usual teaching is that you should get a TSH done on these people, if they haven’t had a TSH done recently,” Joffe says. “Just to rule out the possibility that this is in fact thyroid disease and not psychiatric illness.”

Joffe says the problem is not that people are being overlooked for thyroid disorders but rather, thyroid dysfunction and its symptoms are so vague or similar to psychiatric illness it’s hard to know what is causing what. And therefore, it’s hard to both recognize and treat.

“Psychiatric disorders, particularly depression and anxiety, are very common,” says Joffe. “And then thyroid disease is not as common.” Without a TSH thyroid screening, Joffe calls it “often impossible” to distinguish if the psychiatric problem is due to a thyroid problem or a psychiatric problem. To avoid misdiagnosis, Joffe says as a general principle clinicians are taught that anybody who comes in with a psychiatric disorder could have an underlying medical disorder with physiological symptoms, like thyroid disease. Therefore, they should be checked for that first.

But things get murkier when it comes to subclinical thyroid dysfunction. The term refers to conditions where symptoms and hormone levels are not bad enough to be a clinical disorder, but bad enough to produce effects. That is where controversy lies, says Joffe. It is unclear whether the symptoms of these patients — who occupy an even murkier middle ground of “well but not well” — actually have to do with the thyroid gland or not. These symptoms include fatigue, weight gain, dry skin and depression. “The question with these symptoms is: do you have a common thyroid disorder and a separate psychiatric disorder? Or are they causally related?” Joffe points to another implied controversy: when do you treat a thyroid problem? “There’s a whole lot of debate about when does subclinical hypothyroidism become important,” he says.

According to clinicians like Joffe and Cheng, testing is particularly important for women, for whom both thyroid dysfunction and anxiety are more prevalent. I was 19 when I was diagnosed with hypothyroidism after experiencing symptoms of anxiety and fatigue throughout high school and my freshman year of college. Like many 19-year-olds, I felt tired, stressed and anxious. On good days, I joked it off with friends. On bad days, I felt a hollow depression or nervous anxiety, sleeping until I could start fresh again the next day. I didn’t see a doctor about these times, which came and went with the smallest provocations—a pinprick stain on my sweater, an unanswered email. I would tell people, “Girl problems, that’s all.” Besides, I had regular check-ups, tried to eat healthy and went to the gym every day. I was, from all appearances on paper and in person — “healthy.”

But like Caroline Walsh, the disturbances got worse. And when I finally learned my hypothyroidism was the source of my instability, I felt relief. There existed a physiological source for my tiredness, depression and feeling out of control. It was the result of hormonal fluctuations inside the thyroid that on my best days, I just couldn’t feel or see. And after my diagnosis there followed a series of blood tests, prescriptions and doctor’s visits, scheduled months ahead of time in linear charts and neat black ink. Stability, after so much dissent.

6 Comments

TSH is a hormone produced by the pituitary gland.

Many times thyroid problems are related to infections. Namely Lyme and

Co infections. It has taken me years to figure out why I was Hypothyroid and hypoglycemic but now I am sure it’s because I have/had unchecked,untreated and misdiagnosed infections. Not everyone of course, damage to the pituitary gland or even trauma have been named for thyroid problems also.

I was diagnosed with hypothyroidism back in 1998, since 2010 I have not had health insurance and only have had the opportunity for my synthroid on a daily basis when I apply for medical assistance which lasts as long as the denial so a months if that.. I have gone back in to the doctor to get another script hoping my insurance wouldnt be an issue however they did tell me if i kept on not taking my medication i was going to kill myself not that it matters my question is the generic stuff you can buy from other places is that stuff okay and even legitimate because i was told and even had it put in wrting by my doctor i was at risk for a mixaderm coma and was metebolicly deranged half of me was one temperature than the other same with oxygen levels as well as heart rate i was also having an issue with a seizure when the pen light was put at my left eye when i was told to look up at the right corner of the room what does any of this mean for my health and future i also was diagnosed back in 2003 with an unexplainable mass on the top part of my brain plus i was in a bad car accident in 2009 and have also been diagnosed with neuroapathy from that reading online med web sites i see that both of my situations could be masked with the other what do i do and how do i help myself as i have been uncared for now for almost 4 1/2 years. Sincerely kylie schelble

This article is highlighting a problem that I have suffered from my entire adult life. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. It means you are hypothyroid most of the time but during a flare up become hyperthyroid. This means you can have periods of anxiety, panick attacks, tremors etc. but then feel tired and cold the rest of the time. It is extremely difficult to get a diagnosis in this country and damn near impossible to get any sort of reliable treatment. I am glad to see it is being looked at though, gives me hope that someone may find out more about the condition & that GPs will stop doling out antidepressants and antianxiety pills because they don’t have anything else to give you!

I beg to differ with the assumption that the TSH test is the only reliable blood test to determine hypothyroidism. Everybody know now that it is a lousy test for determining thyroid function. I had been undiagnosed for 18 years and my depression and anxiety was steadily getting worse until I was suidical like the poor woman depicted in the article. I only found out after I was a physical and mental mess that I was indeed hypothyroid by going to a gp/natripath that I was severely lacking in thyroid hormone or reverse T3. Once I had my first NDT tablet the anxiety dissipated in one hour!!!. The TSH test is NOT reliable .

very enlightening information