The (de-)evolution of the bulldog

Here’s how a powerful breed of guard dogs turned into humanity’s cruelest genetics experiment

Dan Robitzski • September 25, 2017

Over just 100 years, the English bulldog has undergone an unfortunate transformation. Unsustainable generations of selective inbreeding have exaggerated the breed's features to an unhealthy, extreme degree. [Image courtesy of Caen Elegans]

Humans have been deliberately breeding dogs to have specific traits and appearances for centuries. That’s why even though all dogs are members of the same species, we have pups that are teeny, gigantic, round and long. And, in the case of the bulldog, just generally sad-looking.

Because this aesthetic-based genetic engineering happened without understanding the, you know, genetics, each new appearance came with changes beneath the surface.

When we raise different dog breeds to have different traits, we are also causing a number of health problems along the way. As such, a number of dogs have shorter lifespans than they used to, thanks to problems with their hearts, livers, bones and other maladies. Bulldogs have it worse than any other type of dog — they tend to develop heart problems, hip problems, breathing difficulties and a whole slew of other health issues that emerged after generations and generations of inbreeding. Modern English Bulldogs rarely live longer than six human years or just 42 dog years.

The bulldog situation has become particularly dire. A 2016 study published in Canine Genetics and Epidemiology concluded the bulldog subspecies is past the point of no return. The authors argue that we have so severely reduced the amount of genetic variability among bulldogs, that introducing new, healthy genes into English Bulldogs and other breeds now probably wouldn’t improve their lot.

So how did a breed of dogs that used to be known for its strength and resilience turn into the sick and short-lived modern bulldog? Here’s what we know about their past.

12,000 B.C.: The gray wolf

The ancestor of all domesticated dogs. [Image credit: flickr / Ronnie MacDonald | CC BY 2.0]

In the last decade, geneticists have conducted a great deal of research into the mutations that turned gray wolves into modern dogs.

What likely happened is that some wolves who were naturally more social and less aggressive would venture closer to human settlements and rely on their scraps as a food source. Over time and through selection, those friendlier traits would have been passed on to their offspring, generating a breed of social proto-dogs, explains Dr. Krishna Veeramah, a population geneticist at Stony Brook University.

“The first specimen that we can say is a dog, not a wolf, is 14,000 years old from Germany,” says Veeramah. “But there are other specimens that people say ‘Oh, that looks like a dog,’ but it’s difficult to say that’s not a small wolf.”

That initial domestication had a range of physical implications, like dogs developing the ability to digest the starch and fats so common among human foods. These genetic changes allowed dogs to subsist on agricultural scraps and whatever meat was left behind when humans and dogs hunted side by side.

But domestication mostly happened in the brain. A 2004 study found that domesticated dogs have altered production of two neuropeptides that help determine behavior, CALCB and NPY. These mutations led to notable differences between the prefrontal cortices of dogs and wolves, according to another genetics study from 2013. The prefrontal cortex is associated with higher levels of cognition and social behaviors, so this may have been the big neurological jump that gave dogs the ability to be nice to us.

From there, the story of the bulldog is just fine — or, rather, not-so-fine — tuning.

Ancient Rome: The pugnaces Britanniae

Early ancestors of the bulldog fought alongside British soldiers. The ancient dogs also battled in the Coliseum. [Image courtesy of ArqueHistoria]

Ancient Roman records include mention of both British and Greek soldiers fighting alongside large, ferocious dogs. Records of both the Greek Molossian dogs and the pugnaces Britanniae, or “broad-mouthed dogs of Britain” describe dogs that are similar in appearance to early bulldogs. So similar, in fact, that University of California historians assert that the pugnaces Britanniae is likely the ancestor of the Alaunt and, in turn, the modern English Bulldog.

The Middle Ages: The Alaunt and the mastiff

The paper trail gets a bit murky, but the British Alaunt is likely a distant ancestor of the modern bulldog. [Image credit: Wikimedia Commons / fenrunna | CC BY-SA 4.0]

The terminology used to describe different dog breeds has changed over time, so the earliest known ancestor of the bulldog is still subject to debate. But historical records suggest that the alaunt is likely the common ancestor shared by the bulldog and the mastiff, which was brought over from Asia. However, many say that bulldogs descended from mastiffs. While it’s likely that the dogs are related, “mastiff” used to be a general term for large dogs so the bulldog’s earliest origins remain unclear.

An 1890s depiction of bull baiting with dogs experiencing varying degrees of success. [Image credit: Samuel Henry Alkin | Public Domain]

Mastiffs, native to Tibet, descended from Chinese dogs. According to a genetics paper published in Molecular Biology and Evolution in 2014, these mastiffs differentiated from their ancestors through genetic mutations that helped them survive at extremely high altitudes. Some of these mutations, which include alterations in multiple genes, are the same as those found in people who have also adapted to survive at high altitudes.

In 13th century England, mastiffs became common in staged bull baiting, where one or multiple dogs would try to bring down an angry bull by latching onto its nose with their teeth and trying to drag it to the ground. The bulls, in turn, would keep their heads low to the ground and defend themselves by launching the dogs into the air with their horns.

The Renaissance: Dogo de Burgos and the Bulldogg

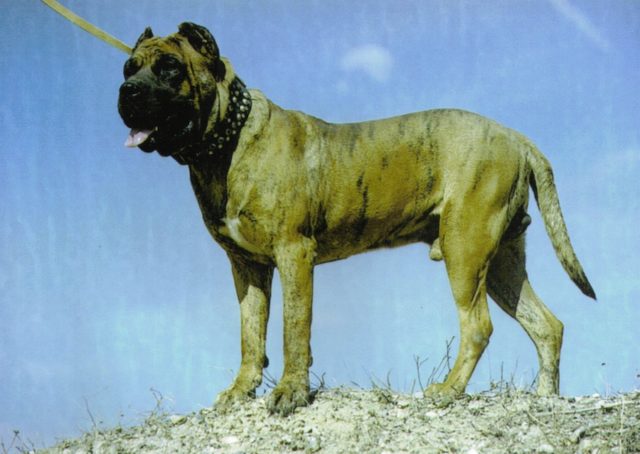

A cuban mastiff, which is very similar to the burgos mastiff. [Image credit: Dog Breed Standards | CC BY-SA 3.0]

In 1900, an Englishman named John Proctor bought a plaque from the French Bulldog breeder A. Provendier. The plaque, which was dated back to 1625, was labeled “Dogo de Burgos,” and depicted a Burgos Mastiff. At that point in time, the Burgos Mastiff strongly resembled a modern bulldog.

And in 1631, a letter sent from Spain to London requested a shipment including, “…a good Mastive dog, a case of liquor and I beg you to get for me some good bulldoggs.” These were the first times in written history that bulldogs and mastiffs were differentiated as separate breeds.

In the book Of English Dogs written by Johannes Caius in 1576, the mastive or bandogge are still considered the same, and are described as a large, stubborn, loyal dog that was used to bait bulls. The two breeds must have been distinguished from one another shortly after that.

1800: The Bulldog

The bulldog, as it appeared in the 1800 Cynographia Britannica. [Image credit: Cynographia Britannica | Public Domain]

A physical description of the bulldog appeared in the 1800 Cynographia Britannica, a text providing images and descriptions of various dog breeds. The description of the bulldog mentioned its round head, short nose, small ears and wide, muscular frame and legs.

Bull baiting was outlawed in England in 1802. The ban wasn’t enforced for another 33 years, but once it was, purebred bulldogs dropped in popularity. Some were crossed with terriers to produce a dog that would be better at fighting. In general, crossbreeding bulldogs with other dogs became more popular over this period of time.

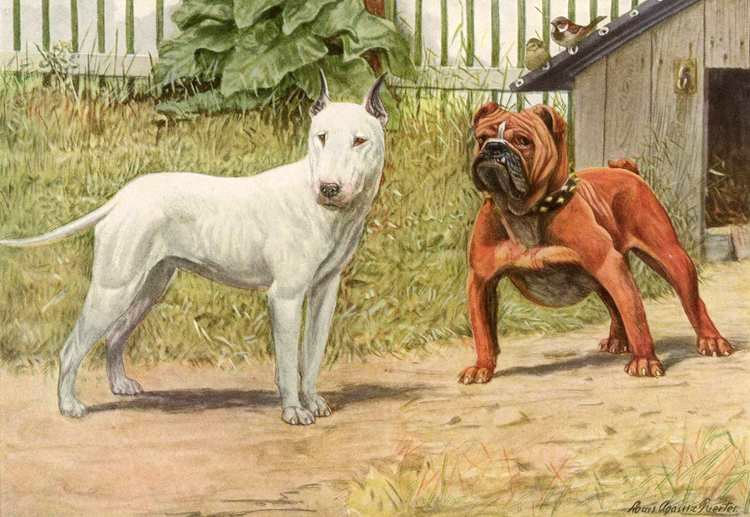

A 1919 depiction of a bull terrier next to an English bulldog. Like the bulldog, the bull terrier is now facing health problems as well. [Image credit: Louis Agassiz Fuertes | Public Domain]

That 2016 study in Canine Genetics and Epidemiology — the one that looked at just how limited the bulldog genome had become — analyzed the genetic makeup of purebred bulldogs and verified that they descended from mastiffs. It also found that at some point, bulldogs had been crossed with pugs. This bizarre combination may explain some of the changes over time to the skull and face of modern bulldogs.

Victorian Era: Selective breeding

The English bulldog, as it was in 1911. [Image credit: flickr / internetarchivebookimages | No known copyright restrictions]

It was during the reign of Queen Victoria, who ruled from 1837 to 1901, that breeding dogs into specific, often funny-looking breeds came into fashion. As contests became increasingly popular and accessible over this time period, so too grew the number of breeds for which one might win an award. “The vast majority of dogs that people have as pets really arrived from the Victorian era from very active breeding,” says Veeramah. “There are rather few ‘ancient breeds.’”

Because this period is marked by actively altering dogs’ appearances, it coincides with an explosive change in dog genetics as well. “Each breed foundation will have made a difference to the gene pool,” says David Sargan, a geneticist at Cambridge University.

As dogs were bred to have specific traits, often to cartoonish extents, their gene pools became increasingly limited and breeds became more inbred. “Every time you create a bit of genetic variation that makes you an animal that you don’t like as much — and some of those might have health benefits — you don’t breed from those,” Sargan says.

Dogs were often bred to have extreme features because people associated those features with certain dogs, creating a vicious cycle of caricature-like exaggeration that caused serious health problems down the line. The perception of what made a bulldog was based on what made a dog good at bull baiting: heavy muscling, a robust skeleton and a big chest. And as those features were accentuated in subsequent generations, explains Sargan, people took them to be the new average and continued to breed for them.

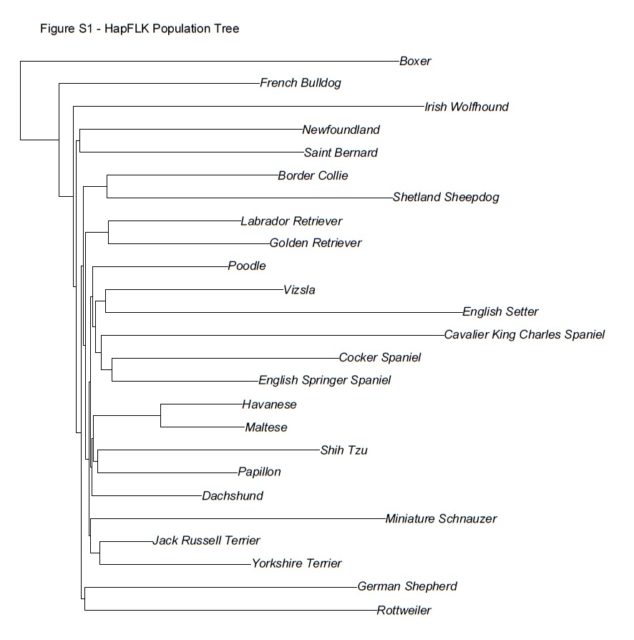

Genetic analysis reveals that the French bulldog shares an ancestor with the boxer, but most breeds emerged after the bulldog had already taken shape. [Image courtesy of Molecular Ecology]

In 2016, scientists from Cornell University ran a genetic profile of 25 dog breeds, including the French Bulldog. They found that bulldogs emerged as a specific breed relatively early on the gigantic dog family tree, so they weren’t the result of crossing different breeds.

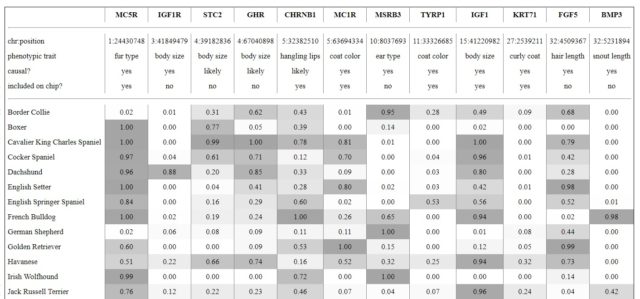

An analysis of select genes responsible for different traits reveals exactly how dogs mutated into different breeds. [Image courtesy of Molecular Ecology]

They also found specific mutations that defined different breeds. Relative to other dogs, French Bulldogs showed high rates of mutation in genes like MC5R which controls the type of fur a dog grows, CHRNB1, which gives dogs droopy, hanging lips, IGF1, which gives dogs a bigger body size, and BMP3, which shortened the length of their snout. These changes happened over time, as dogs were selected for breeding based on having the most “bulldog-like” appearances.

“Part of it is you’re a breeder and you read a breed standard that says ‘large head,’” says Sargan, “so you look at a litter of pups and you see the one with the largest head and say ‘Oh, that must be closest to the breed standard.’”

Present Day: Inbreeding and Health Issues

As we exaggerated their features, we made life pretty difficult for these smooshy little guys. [Image credit: pixabay / Anget611 | CC0 1.0]

Since the 1800s, the number of purebred bulldogs has declined. In fact, the research study from 2016 that said it may be too late to save bulldogs cited evidence that the entirety of the English Bulldog population was bred from just 68 individuals.

According to Sargan’s research, there has been very little new genetic variation over the last 150 years. Today’s bulldogs look mean and intimidating but tend to be docile, brave and friendly with children, in part because of their high tolerance for pain. This can have some drawbacks, though, as bulldogs may not complain or indicate to their humans when they are hungry or in pain.

Even though some breeders claim that they are raising dogs that are designed to be healthy, the real goal of bulldog breeders seems to be selecting for cartoonish musculature and exaggerated features that wouldn’t be found in healthy animals. “I don’t think anyone has deliberately bred against welfare,” says Sargan, “but there’s a lot of feeling that if your dog doesn’t show early disease, then you don’t need to worry about it.”

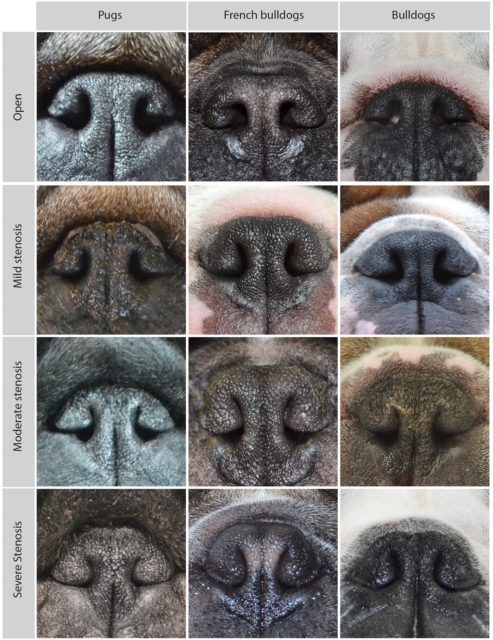

And that causes a lot of problems because bulldogs are one of the least healthy breeds out there. In particular, Sargan’s lab has spent five years studying why bulldogs have such difficulty breathing, a particularly pronounced problem in the breed, alongside displaced hips. The difficulty in discerning healthy dogs from dogs with breathing problems comes from the fact that their snouts look very similar; the difference comes from the sizes of their floppy tongues and oversized soft palettes.

These very boopable noses show the difference between the bulldog’s original, open nostrils and the closed nostrils that the breed developed over time. [Image credit: PLOS ONE | CC BY 4.0]

One possible solution is outbreeding, or crossing bulldogs with healthier breeds so their offspring have fewer health issues. While this would eradicate the modern bulldog, it could give rise to healthier pups.

Outbreeding could work very quickly, but it would be hard for people to accept. Bulldogs are popular among people looking for a companion animal — because they take exercise slowly, people often assume that bulldogs don’t need exercise and make good friends for people who can’t lead active lifestyles.

“The public like these dogs partly because they’re cute and they snuffle,” says Sargan. He says that bad breathing has become an accepted trait rather than an alarming health concern among bulldog fans, simply because it’s become common within the breed.

Even bulldogs, which many take to be lazy, sniffly pals, need exercise too. [Image credit: flickr / lora_313 | CC BY 2.0]

Another tool, which Sargan feels is more likely to help, is to continue identifying the genetic markers of healthy dogs and breeding for them. Of course, as he points out, removing the poorer candidates from the gene pool will only make the bulldog even more inbred than before, possibly bringing forth new health issues controlled by recessive genes.

Breeders have been quick to adopt the necessary changes to prevent simple genetic disorders, but breeding for overall health is much more complex. What might help is to accept that some bad traits will still be passed on and assign different bulldogs breeding values. That value would be a ranking based on their health factored with some less-critical unhealthy traits that would inevitably get passed on to their offspring. While this approach wouldn’t eradicate all of the problems that bulldogs face, it would at least help while keeping their genetic variance at slightly higher levels.

“We create fingerprints of most of the things we want,” says Sargan, who pointed out that breeding based on genetics rather than appearance will make the practice much more accurate in the future.

Because decades and decades of inbreeding among a very small group of animals has knocked out any sort of genetic variety within the breed, the resulting health problems from which modern bulldogs suffer may be inescapable. Whether we leave them as they are or we try to alleviate their problems, it’s possible that the purebred English bulldog won’t be around for much longer.

16 Comments

The picture you captioned as “the English bulldog as it was in 1911” is actually a French Bulldog, a distinct and separate breed. You don’t have to take my word for it; the link associated with the picture also states that it’s a French Bulldog.

One other thing- the site linked to under the “Cuban Bulldog,” (the dog breed standards site), has no “Cuban Bulldog” listed as an existing or extinct breed, so whatever that dog it, it’s not what it’s labeled in this article.

The bulldogge (sic) breeder linked to in the section about “cartoonish musculature” isn’t breeding English Bulldogs, he is breeding Olde English Bulldogges.

I may be mistaken, but I believe the breeder added the ‘Olde’ because while he was breeding English Bulldogs, he was also breeding them with other dog breeds. So, technically, they can’t qualify as English Bulldogs anymore. (Also, ‘Olde English Bulldogges’ sounds WAY better than ‘Mostly English Bulldogs’. Since he is essentially creating a new breed, and modeling it on an older English Bulldog breed standard, I suppose it makes sense.) Heck, I just feel bad for the poor little guys!

I love the English bulldog breed. But yes, I agree that its evolution has mainly impaired in your breathing. The summer for them is terrible.

6 years? So my 8 year old bulldog is an anomaly. The site for dog breeds says the bulldog lives 8-10 years. 10 years is too short a time for our best friends, and 6 is terrifying.

I disagree with 6yrs also.i would double that.my first english was 14 when we put her down.the 2nd is 14 now and healthy as heck.regular walking(1 mile for mine max.lol.)and yearly checkups is all we do.along with a good diet of good DRY food portioned because mine will eat the whole bag nonstop!!lol.BEST bundles of love…

8-10 is the standard. They do require a lot of care and those owners who put in the time the love and responsibility will do wonders for the quality and longevity of the dogs life. I mean daily wiping, cleaning every fold or wrinkle of skin. Looking for dry patches catching and treating any issue asap. Proper diet a must. No forced activity. 20-30 mins a day is plenty. A lot of work but so much reward for dog and owner in return.

I do not have an English bulldog or is these folks would say old English bulldog but I did grow up with one my grandfather’s was my best friend. I think whether you guys agree with what the article has said what contradicting it like several of these folks the basic message was is it they are in trouble as a whole not the few exceptions that some folks have did they taking really good care of I think what you need to walk away from this with is it if you love the breed as I have my entire life I just can’t afford one of them they are definitely endanger so if you have one take extra care of him or her

This article is very misinformed….I think the author did not do his ” homework “…just seems to criticize all the hard work people ( breeders) have put into the breed…just an fyi…many breeds have trouble breathing in the heat..( shih tzu’s..peaks..etc..) not just the bulldogs…also my Bulldogs have lived long past 6 yrs old…currently have an 11 years old..and still going STRONG!!

I think Dan used his minor in creative writing more so than he did his major in neuroscience in creating this piece of work. The erroneous captions accompanying nearly every image leads me to believe that his other statements of fact may not actually be facts at all.

Jeeze, everyone is apparently here to burn Dan or say that their dog lived longer than he stated… Your captions were fun and informative, I appreciate the research you laid out, and overall it was a good read. I think people label certain thongs as ‘cute’ when they are really dangerous/unfortunate like smashed faces, obesity, dwarfism, etc… I hope they can save the breeds personality, because that is more important than anything else.

wow, everyone is really hating on the author but I guess that is what the internet was designed to do.

Great article. Sadly, the Bull Dog is not the only breed that has suffered irrational breeding ideals. Too much emphases is placed on form rather than function in many breeds today. The sooner we take a step back and re-think things the better.

first time reader ever had one .but every time i seen one big rush of happyness 6 years to 14 years but the bull dog left me happy ever single time i seen one

How about my American bulldog?

I’ve been looking after a rescued English bulldog 6months now and I’ve had more exercise fun and general well being than I have in the past 6years .

And they do say be careful what you wish for it might come true and not just for me but this handsome beast I inherited.

It’s not rocket science and I’ve only ever looked after one other dog in my life but if you’re struggling there’s a lot of help and support out there and not everyone is out to rip you which is why it really is good to shop around for a better deal elsewhere