Is there a reason for grief?

Scientists are tackling this all-consuming emotion

Katherine Ellen Foley • July 30, 2015

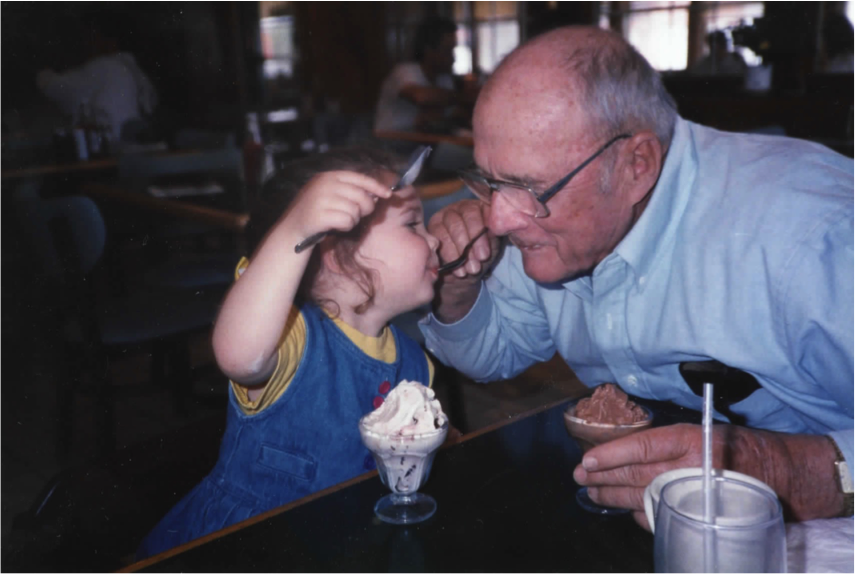

My late grandfather Joe Frank Foley and I sharing some ice cream, circa 1996. Courtesy of Joe Preston Foley.

I was 11 years old when my paternal grandfather had a heart attack and died in his recliner. Even though he lived a twelve-hour drive away from us on a farm in Versailles, Kentucky (pronounced “Ver-SAILS”), we visited at least twice a year. He was the one person in the family who called me “Katie.”

I was heartbroken when he passed, but I know it was harder for my father. It was one of three times I have ever seen him cry.

Sadness and bereavement can leave us listless, withdrawn and awake all hours of the night. Sometimes, we may physically ache for our lost loved one. Columbia University psychiatrist Katherine Shear recently documented a condition called “complicated grief,” in which these symptoms last much longer than expected. And then there’s broken-hearted syndrome, where stress hormones may cause the heart to beat irregularly, mimicking a heart attack. If grief has such terrible effects on our physical well-being, what possible biological benefit could come from unpleasant emotions, such as sadness and bereavement?

Physiologically, grief affects our bodies like stress. It can weaken our immunity, raise our blood pressure and interfere with our sleeping and eating patterns. Our bodies release cortisol, a hormone that triggers our fight-or-flight response. Sometimes, cortisol can be helpful; it can prepare us to accomplish a physical feat or complete a task under pressure. But in the long term, it can be detrimental to our health.

One way to determine if grief has a biological purpose is to see if animals do the same. Barbara J. King, an anthropologist at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, suggests that there may be an evolutionary basis for grief — at least in animals. “It seems to me that grief is the flip side of very close emotional attachment,” she said.

King has researched a variety of types of animals, and in 2013 published a book collecting observations of grief-like behavior from all over the animal kingdom. She tracked down stories of large-brained mammals, such as dolphins and elephants, to those with smaller brains, such as house cats and ducks. In each example she found, animals changed their behavior in a way that mimicked typical signs of human grief after a death close to them. They became withdrawn, less interested in socializing, restless or unable to eat or sleep.

King believes that animals could be compassionate and empathetic, and hypothesizes that the reasons animals show signs of grieving is because it’s a necessary process. “One of the suggestions is that grief is the time the body takes to mourn and repair [after a loss].” When two animals have a companionship, they grow accustomed to one another’s presence, and may even rely on each other for activities such as feeding or playing. After one passes away, the other may have to relearn certain routines, and adjust to life by itself.

Though others have also seen signs of grieving in the animal world, they disagree that it’s possible to say they feel the same emotion we do. Richard Byrne, a cognitive psychologist at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, studies the way that animals behave as a way to understand human behavioral traits. He and his colleagues published a paper in 2008 that explained that elephants — which have been known show interest in other dead elephants — show empathy, but that this doesn’t necessarily mean they feel a particular emotion like grief. While they may be aware of one another, and may even try to help one another in certain situations, it’s hard to say that they officially grieve without knowing what’s motivating their behavior after a loss.

However, he doesn’t think that grief can be entirely ruled out, either. According to Byrne, you can typically assume that a person is grieving when his or her behavior changes dramatically after a death of a loved one or another major loss. Why shouldn’t that logic be extended to animals, even if they can’t verbally communicate it to us? Byrne thinks that it’s something that anthropologists and biologists may never be able to prove, whereas King feels this same phenomenon is evidence that animals do grieve.

So, grief in animals is still up for debate.

Psychologists have another perspective: As it turns out, sadness and grief are not the same, even though we tend to group them together in the same family of upsetting emotions. According to J. John Mann, a psychiatrist from Columbia University, sadness is a part of grief: When we are sad, we want something to change. “It’s a motivation to reestablish a relationship,” he said. If we are sad to be separated from someone we love for a period of time, we’re even happier to see each other when we’re reunited. He views grief, though, as a deep yearning, and said that sadness is a tool that we use to resolve our immediate bereavement into a more permanent memory of a lost loved one.

Randolph Nesse, a psychiatrist and director of the Center for Evolution and Medicine at Arizona State University, says that grief is a specialized form of sadness to help us cope with a life-altering event. “When you lose something that’s important, that’s a very adaptively significant event,” he said. At first, I wanted to dismiss this fact as a clinical explanation, but there’s some truth there: When I think of grief, I tend to think of my life before a loss, and then life after. The loss cleaves my time into different chapters.

Nesse, though, firmly believes that there isn’t one purpose for any emotion. “Emotions have many functions,” he said. “What we should be trying to do is understand in what situation an emotion is useful.” He nonetheless thinks “the idea that grief may be a useful biological trait that is shaped by natural selection seems both preposterous and somewhat cold-blooded,” which he wrote in a book discussing how grief affects older couples. He points out that understanding the mechanics of grief doesn’t make it any less painful.

I remember Granddaddy’s raspy voice. He was quick to laugh and one of the smartest men I’ve ever known. Maybe I’m an overly practical person, but I hope that anthropologists and psychologists pin down a practical reason for grief soon. Then, just maybe, his memory will be a little brighter.

7 Comments

Life is simple, and yet colorful; life is boring, and yet beautiful; life is irregular, and yet agreed. We don’t need to grief or we shouldn’t, what we should do is to enjoy the life better.

I read two books on grief to prepare myself for my mother’s eventual passing being that she was in hospice-never thinking my husband would pass first, though he had been sick for some time, but had no fatal diagnosis.

But then he died last summer. My mother remains in hospice.

The books helped and help me now but until it happened to me, I didn’t really begin to know.

Grief IS different from sadness though like the article states, sadness is a symptom of grief.

I met my husband 42 years ago and we rarely spent time apart since. We raised a family, became grandparents, recently moved into our dream home for our retirement. He never got to enjoy it.

I have known others in the past who’ve lost a spouse, known it is very hard for them, the grief. We all tend to intellectualize grief. But then it happened to me. And BOOM! It is an entirely different experience than I imagined. It can be physically painful at times. I had a hard time eating or sleeping. I lost 14 lbs and I am already thin. I have been staying up all hours of the night. For a month or so, I could not even sleep in our bed. There are no words to describe how it really feels. How it sneaks up on you when you are least prepared or expect it. How you can be feeling sort of ok then hit over the head with your grief and begin crying or become angry and shout into the air to no one. Or maybe to the one who left me behind. The deep missing, yearning cannot be adequately explained. I miss the future I thought we had. I expected to have. I miss him! I miss being hugged. No one hugs you when you live alone. I still sleep on “my” side of the bed. I still want to talk to my husband so bad. When will that feeling go away?? Who knows. This is still the beginning of the grief process for me. The other part of grief is discovering who I am now. I am no longer a wife. No one to discuss dinner plans. I have known him most of my life. So where to go from here? I grieve for many, many things.

People offer comfort in intellectual phrases that sound good, maybe the TV sound bytes from the “experts.” It is all our society knows to do. But take it from me, it’s all useless garbage. Of no help. Sometimes it is actually hurtful to hear. I just need you to be there. To listen. You can’t fix my pain. In many ways, it is a solo journey only I can travel. I just need support and love to smooth some of my rough waters. I am grateful I do have some very wonderful family and friends. And they help.

But in the end, I am just floating anyway. Holding onto a piece of wreckage from my past until I find my present.

I am finding grief to be a very complicated life process. I am still living, my husband is not. How do I make sense of that?

I am already learning that you don’t. You just go on.

I have been dealing with a lot of grief since my mom passed away and I am wondering if this is something I need to get over and ask for support with. You make a great point that allowing grief to overtake me will lead to psychological and even physical distress over time. This makes me think that getting support for my grief could help me not only mentally but physically as well.

@nancy_koleda, I read your comment and quite literally cried (while I sat eating in a restaurant; a waiter came up and just handed me a tissue). Like you, I’ve also been mentally preparing myself for the loss of my aging mother, the single most important person in my life. Even the thought of her absence leaves me paralyzed. But I’m young – early 30’s – and a long life after her absence is unimaginable, almost unbearable. I always ask her why she had me so late in her life, and how unfair it is for her to love me so much but for for such a short time (compared to my older siblings). She always reminds me that she lived this long only because of me, wanting to see me grow up. I’ve tried to rationalize it all – death, love, life, etc. I see everything in these logical ‘bytes’ you’ve mentioned. But only one thing escapes this rationalization – the pre-grief for my mother. Anyways, thought I’d share. Sending you lots of love wherever you are.

Nancy,

My wife of 41 years passed away last year … tonight was having a tough moment, so I thought I’d try to find something on ‘why did humans evolve to grieve’ … then I saw your note… every word you wrote is exactly my world. Thank you for putting words to what I’ve been unable to adequately express

Thank Ms. Foley for a very well researched and written article. Yours was enlightening compared to others when I searched Google for “purpose of grief”. Most results were mortuaries…

Thank you again for yours, SB

Humans search for meaning, that’s what defines them. It would be of great comfort when grieving to know that there is purpose in such annihilating pain. I suppose you find your own meaning. Mine is that the extent of grief is a measure of the depth of love felt for the person who has gone. To feel very deep grief is to know the privilege of very great love and that is life’s treasure and the solid ground, if there is one, of human existence.