Putting a face to crime

Forensic artist Stephen Mancusi creates “bad guy drawings”

Sandy Ong • March 7, 2016

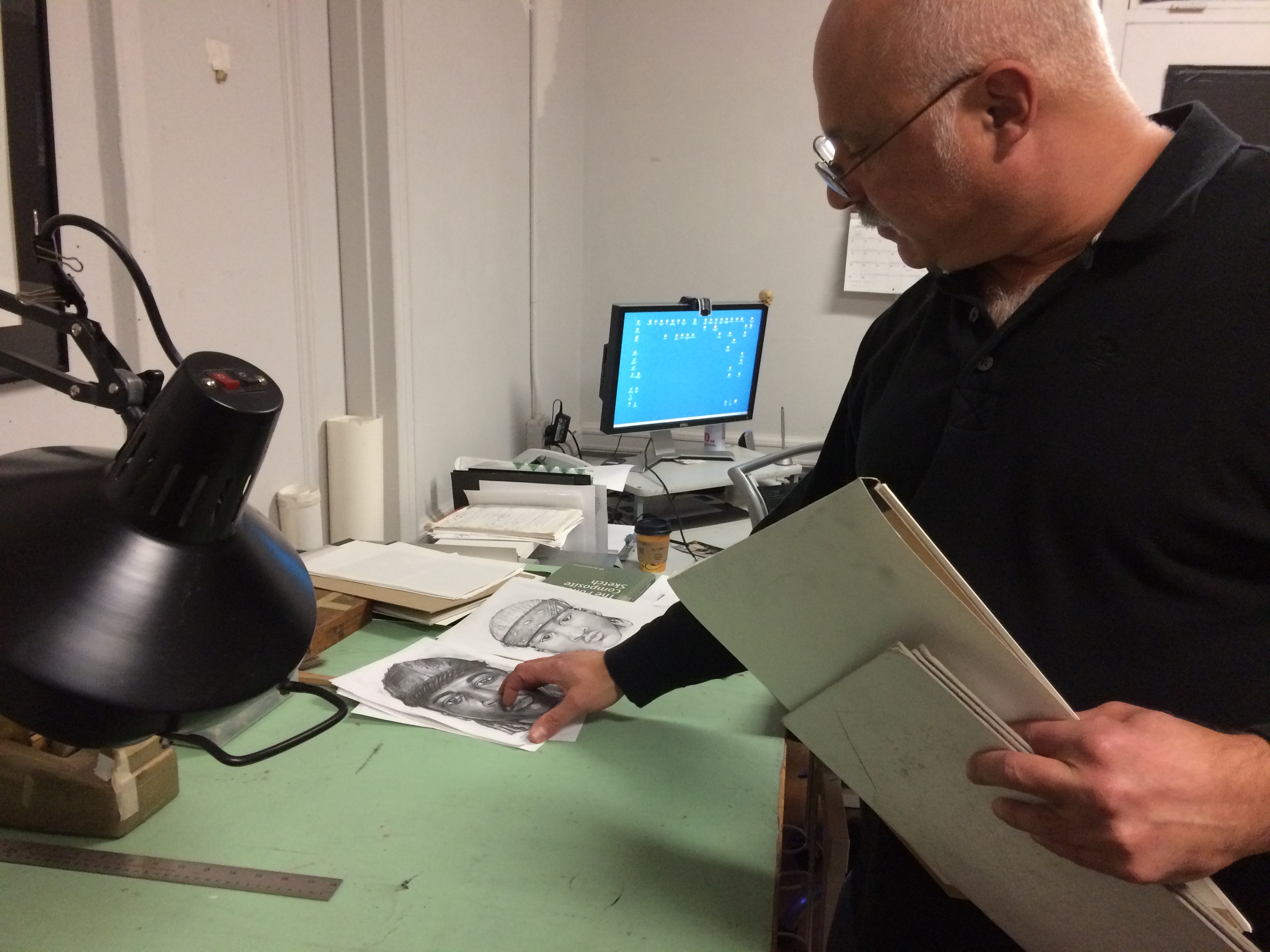

Forensic artist Stephen Mancusi in his Peekskill, NY, studio, explaining how he creates a composite sketch. [Image credit: Sandy Ong]

Stephen Mancusi’s hands flew deftly across the sketchpad. Lightly clasping a drawing pencil, he quickly filled in the initial broad strokes. Soon the vague lines began to take on a life of their own — thick wavy hair, dark eyes, high cheekbones, prickly chin stubble and a scar across the right cheek. A face now stared out from the page: a face of evil.

Mancusi has done thousands of such composite sketches, what he calls “bad guy drawings”, in his 24 years as a forensic artist with the New York Police Department. He has been involved in several high-profile cases, such as the Stuyvesant Town Serial Rapist and the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

The 57-year-old Mancusi retired from the NYPD in 2008, but he remains active in the forensic art community, which numbers fewer than a hundred full-time members across the country. He currently chairs the Forensic Art certification board of the largest global forensic organization, the International Association for Identification (IAI).

“Mancusi has such love for this work,” says Suzanne Birdwell, a forensic artist with the Texas Ranger Division and fellow IAI member. “Even though he’s retired from the NYPD, he’s definitely not retired from forensic art.”

In 2010, Mancusi published a how-to book called The Police Composite Sketch. Apart from composites, he is skilled in other areas of forensic art, such as image modification (often depicting how a missing child would look years later) and facial reconstruction (recreating a face from a skull). These days, he works out of his studio in Peekskill, New York. Mancusi devotes a large part of his time to teaching, giving lessons online and conducting workshops around the country.

“Mancusi is so passionate about forensic art that it’s just contagious,” says Joe Mullins, a forensic artist at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, who has given lectures with Mancusi.

Yet despite his stellar reputation in the field, Mancusi remains modest. “I’m a good artist,” he says, “but by no stretch of the imagination am I a great one.” He believes that a successful forensic artist isn’t necessarily the most creative guy in the room but is one who works well under pressure and has good people skills.

Mancusi never meets any of the people he sketches. He relies on descriptions from victims and witnesses. “A composite sketch can only be as good as the person you’re interviewing,” he says in his native Brooklyn accent. “You really gotta get the person to open up to you.”

Mancusi may have a tough cop image — smooth bald head, signature moustache, reading glasses perched upon the bridge of his nose — but he’s more like an affable uncle. His friendly demeanor is undoubtedly a key skill for a sketch artist, who often sits down with a distressed victim or witness only hours after a crime has occurred, when their memory is still fresh.

This delicate time is when science begins to weave itself into the artistic process. It’s about understanding how memory is encoded and how it can be elicited, says Mancusi. “It’s not a sketch of the bad guy but a person’s perception of the bad guy.”

A typical composite session, which includes both the interview and drawing, can last up to three hours. Mancusi begins by asking broad questions about the circumstances of the case, or simply “what happened?” Apart from encouraging a person to open up, these questions also help him establish the strength of their memory and psychological state. He then asks about the perpetrator’s specific features.

“I’m really attuned to the first three words they use,” says Mancusi. “As an artist, you work solely on the description you’ve been given. It’s all about the words.”

Part of the process involves showing the victim or witness a series of mug shots, so they can point and say, “his face was this shape” or “he had hair like this.” Mancusi says people find it much easier to recognize features than to recall them.

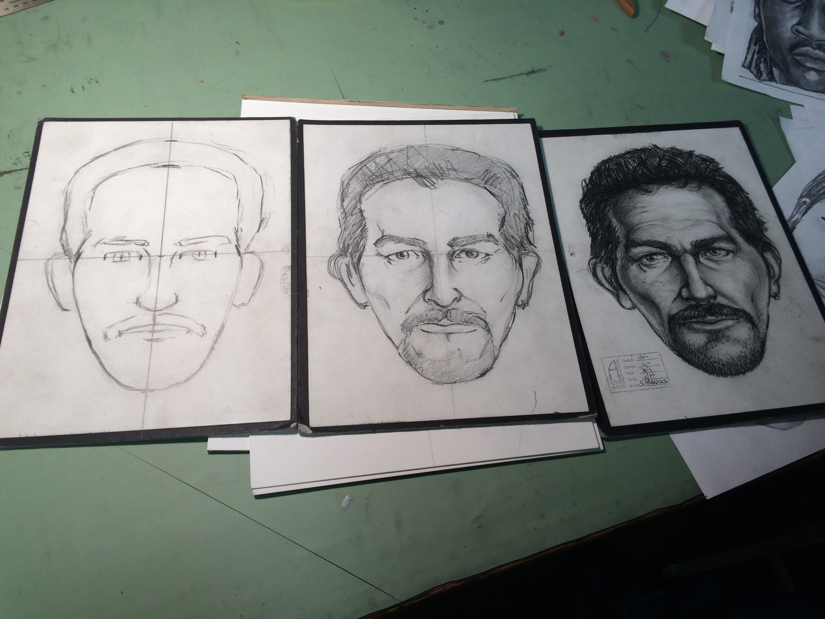

He’s then ready to begin drawing. With knowledge of the suspect’s race and gender, Mancusi first sketches out the facial proportions. He then adds in characteristics such as skin and hair color, what he calls tone. The last step is rendering, where he embellishes the sketch with shading and texture, adding fine details like pock marks, stubble or scars. It’s a fluid process — Mancusi draws and makes adjustments as his interviewee watches and gives feedback.

The three stages of a composite sketch — it begins with getting the proportions right, followed by putting in characteristics like hair color and skin tone. Lastly, a forensic artist adds texture and shading to the sketch to give it that three-dimensional feel. [Image credit: Sandy Ong]

It’s a world Mancusi stumbled into by accident. Armed with an illustration degree from the Fashion Institute of Technology, a young Mancusi initially set out to become a commercial artist. However, the lure of a steady paycheck soon won him over and he worked as a beat cop while trying to get into the select NYPD Artist Unit. Two years went by before a chance opening occurred — one of the Unit’s three artists retired. Mancusi applied for the job and was at his new desk within a month. He never looked back.

Reflecting on his nearly thirty years in the business, Mancusi says one case stands out above the rest — the 9/11 attacks. “It wasn’t my most successful case but it was definitely my most meaningful.”

That day, Mancusi was at the scene looking for his wife, who worked across the street, when the second tower collapsed. Discovering that she had been safely evacuated, Mancusi returned to the police headquarters, dazed and covered in ash. He recalls his colleagues asking where he’d been, saying “We need sketches!” Within hours, he was back at his desk, drawing pencil in hand.

For Mancusi, that moment encapsulated the meaning of being a sketch artist, work that he’s dedicated his entire life to. He says, “the fact that you’re wanted, that I was performing my duty in that context — it’s a tribute to the discipline we’re part of.”

[tribulant_slideshow gallery_id=”3″]

1 Comment

I think that is my drawing he is touching. It was his favorite of my homework. He is a brilliant artist and teacher. I never did anything with the learning. Maybe I will start now.