Can a diet prevent Alzheimer’s Disease?

Studies suggest that heart-healthy diets also associate with a healthy brain

Cici Zhang • February 6, 2017

The Mediterranean diet, composed of vegetables, fruits and oils, may help prevent cardiovascular disease. [Image credit: Flickr user Neil Moralee | CC BY-NC-ND-2.0]

Roy Hardman turns 60 years old this year. A diet and cognition researcher at the Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne, Australia, he’s followed the Mediterranean diet for 15 years. Partly because he doesn’t want to repeat the same mistake his dad did — consuming high amounts of salt, sugar and fat. The result? His dad died of Alzheimer’s disease four years ago at 87 years old.

Although not the sole cause, Hardman thinks that his father’s diet was a contributing factor to the disease based on previous research in the field. He believes it’s important to start following a healthy diet from 50 or even 45 years old. “What you put in your body is going to fix your brain,” said Hardman. “You don’t wake up on your 70th or 71st birthday and say ‘oh I got dementia.’ There’s a 20-30-year progression of the condition.”

Can certain diets really prevent dementia? Let’s look at the evidence.

The Mediterranean diet

Rich in fish, vegetables, fruits, olive oil and nuts, the Mediterranean diet is known as a heart-healthy diet. Recently this diet was linked with brain healthiness, according to a 2014 meta-analysis published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. A meta-analysis is a systematic review that combines relevant data to reach conclusions with a statistical power greater than a single study. The authors analyzed five studies of nearly 4,000 participants and concluded that the Mediterranean diet was associated with a delay of cognitive decline, which is when brain functions like memory or reasoning worsen over time.

It turns out people who stuck more closely to the Mediterranean diet were less likely to develop pre-Alzheimer symptoms, or mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Symptoms of MCI include forgetting recent events or demonstrating poor planning skills — cognitive changes that are noticeable but not severe enough to interfere with daily functions. The Mediterranean diet followers were also less likely to progress from MCI to Alzheimer’s disease.

When it comes to cause-and-effect, however, only one randomized, controlled clinical trial has found the Mediterranean diet protective against cognitive decline. Followers actually showed improved cognitive functions over four years.

In that study, 447 Spanish participants in their late 60s were randomly assigned to follow different diets. They either followed the Mediterranean diet or their normal diet along with advice on how to reduce fat intake.

The two groups following the Mediterranean diet also consumed fixed amounts of extra olive oil or nuts every day. Researchers added these supplements for a better control over the experimental inputs.

Olive oil and nuts are rich in antioxidants. Antioxidants fight against reactive oxygen species in our body, which kill cells — including those in our brains — according to Emilio Ros of Hospital Clínic in Barcelona, Spain. Ros is the main scientist who led the study.

After about four years, the control group told to maintain their diet but with less fat showed cognitive decline — something expected in the aging process. On the other hand, the Mediterranean diet groups showed improvement in their cognitive functions as evidenced by test scores on memorization and attention tasks.

Compared to what they scored in the beginning of the study, the “Mediterranean diet plus olive oil” group had a two percent increase in their scores of memorizing words and names. They had a nine percent increase in performing tasks of attention and execution. The Mediterranean diet plus nuts group had similar improvements over the study period. Basically “those [Mediterranean] diets delayed aging-related cognitive decline,” said Ros.

Compared to the control diet group, “[People taking] the Mediterranean diet plus nuts performed better on memorizing words and names,” said Ros in the video that accompanied the article. The group taking the Mediterranean diet with olive oil performed better on things “requiring a speed of thought,” Ros explained. The performance differences were statistically significant, meaning that they probably did not occur by chance.

Although the study showed that the Mediterranean diet improved cognitive function over the short-term, the study did not examine whether participants developed dementia over the long-term, said Ros. But we should know the answer soon. A paper detailing this “hard outcome,” is currently underway.

The MIND diet

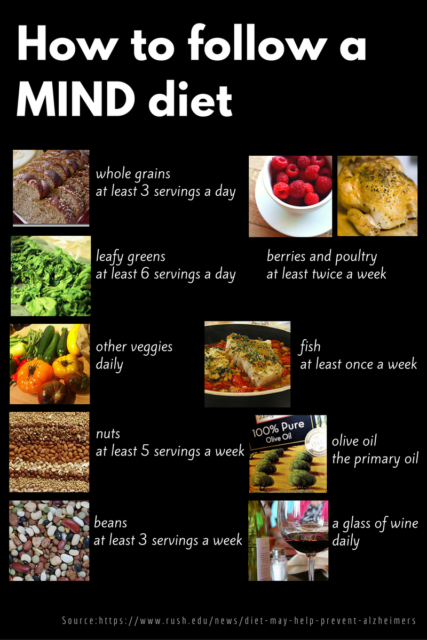

Another diet that has been linked with dementia prevention is the MIND diet, which was created in 2015 by Martha Morris, an epidemiologist from Rush University in Chicago.

The MIND diet is a hybrid of the Mediterranean diet and the DASH diet, or the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension. With this in mind, it’s called the Mediterranean-DASH diet Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND). Featuring plenty of whole grains, fruits, vegetables and low-fat dairy products, DASH is mainly used to reduce high blood pressure.

Not only does it incorporate the basic components of those two diets, the MIND diet also has a unique ingredient — leafy greens. It recommends six cups of raw leafy greens or three cups of cooked leafy greens per day.

Leafy greens are great sources of Vitamin E, which according to Morris can reduce the accumulation of amyloid plaque, a protein in the brain that is associated with the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

The MIND diet might perform better than either the DASH or the Mediterranean diet alone, according to a 2015 study of over 900 participants. In the study, among people who followed these diets most closely, the MIND diet group were 54 percent less likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease, which affects one in nine people age 65 and older. The DASH and the Mediterranean diet group were respectively 39 percent and 53 percent less likely to develop the disease.

However, when people followed these diets with a moderate adherence, said Morris, “Only the MIND diet was associated with lower risk of Alzheimer’s — a 35 percent reduction.”

A clinical trial is underway to move beyond correlation and identify the true cause-and-effect relationship between the MIND diet and cognitive function. It will enroll 600 seniors and evaluate their cognitive function and brain structure after they follow the MIND diet for three years.

Why are these diets brain-healthy?

If any diet were proven to prevent Alzheimer’s disease by randomized, controlled clinical trials, what would be the explanation?

Antioxidants in olive oil and nuts cannot be the sole factor at play because clinical trials have found conflicting results on whether antioxidants can slow cognitive decline. Vitamin E has no solid support either. The Cochrane Library, which provides scientific reviews on health care decision making, pointed out that vitamin E should not be used to treat Alzheimer’s disease. No meta-analysis has analyzed whether vitamin E has a preventive effect.

However, there could be some value in the interaction of different foods in certain diets, wrote neurologist Dr. Nicolaos Scarmeas of Columbia University in an email.

If you don’t take into account what else people are eating, examining the effect of individual foods or nutrients will be problematic, according to Scarmeas. For example, copper consumption only plays a role in the cognitive decline of people following certain diets. “Higher copper consumption is associated with faster cognitive decline only among subjects with high intake of saturated and trans fats,” wrote Scarmeas in the email. An “effect of fish consumption in lowering blood pressure and blood lipids seems to be much more pronounced in subjects following a low-fat diet.”

So that’s why people do research on diets. “When we investigate overall diets, we do not have this problem because different combinations of foods and nutrients are incorporated into the pattern,” wrote Scarmeas.

Besides Hardman’s formal research efforts to understand the relationship between diet and cognition, he recently “recruited” his older brother for a short trial. Hardman’s brother came to visit him and did “a little exercise to go Mediterranean.”

With no steak or sausage, “[My] brother was like ‘hmm I don’t think I’m going to survive.’ But anyway he stuck with the diet for two weeks, and he felt more energetic and his bowels went back into shape,” said Hardman. So there were some visible, fast health benefits of the Mediterranean diet.

But Hardman is cautious too. “There’s an opportunity for [the Mediterranean diet] to reduce the onset of dementia or mild cognitive impairment. We can’t say it’s going to stop dementia. We can say it could potentially help.”