International students face mental health challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic

The crisis has exacerbated long-overlooked anxiety, depression and other mental health problems among this population

Huanjia Zhang • February 5, 2021

Nikita Dhar, a sophomore business administration student at Georgetown University, returned to her home country Singapore as the soaring coronavirus outbreak shut down U.S. college campuses. Since then, she has struggled with mental health issues while fulfilling her role as an international student. [Credit: courtesy of Nikita Dhar]

When colleges and universities across the country closed in March 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Nikita Dhar, a sophomore majoring in business administration at Georgetown University, had less than 24 hours to pack before catching a flight back home to Singapore.

Dhar had tried to book Uber rides to transport some of her belongings, which she crammed into three boxes and suitcases, to a local friend’s house for temporary storage. She requested a van or SUV that could accommodate six people, but two drivers refused to let her put her belongings on the passenger seat. A third driver agreed to take half of her stuff. Another friend, waiting with Dhar out on the street, agreed to store the remaining items.

For Dhar and other international students, the COVID-19 pandemic has added a new layer of stress atop the challenging experience of pursuing higher education in the U.S. Public health measures like social distancing have compounded the loneliness and feelings of homesickness felt by many international students, who already have to navigate language and cultural barriers that contribute to their sense of isolation. Additionally, the logistical challenges of maintaining their legal status in the U.S., stoked by former President Trump’s mercurial immigration policies, also put international students’ mental health in disarray.

More than 1 million international students pursued higher education in the U.S. in the 2018-19 academic year, according to a report co-published by the U.S. Department of State and the New York City-based Institute of International Education, a nonprofit organization that promotes international education and exchange. In 2019-20, international students contributed more than $38 billion to the U.S. economy, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce. Moreover, the National Science Foundation reported that roughly 75% of international science and engineering doctoral students in 2015 intended to stay and work in the U.S.

Though supporting the well-being and mental health of international students aligns with national economic and research interests, some international students felt that support slip away in the past year.

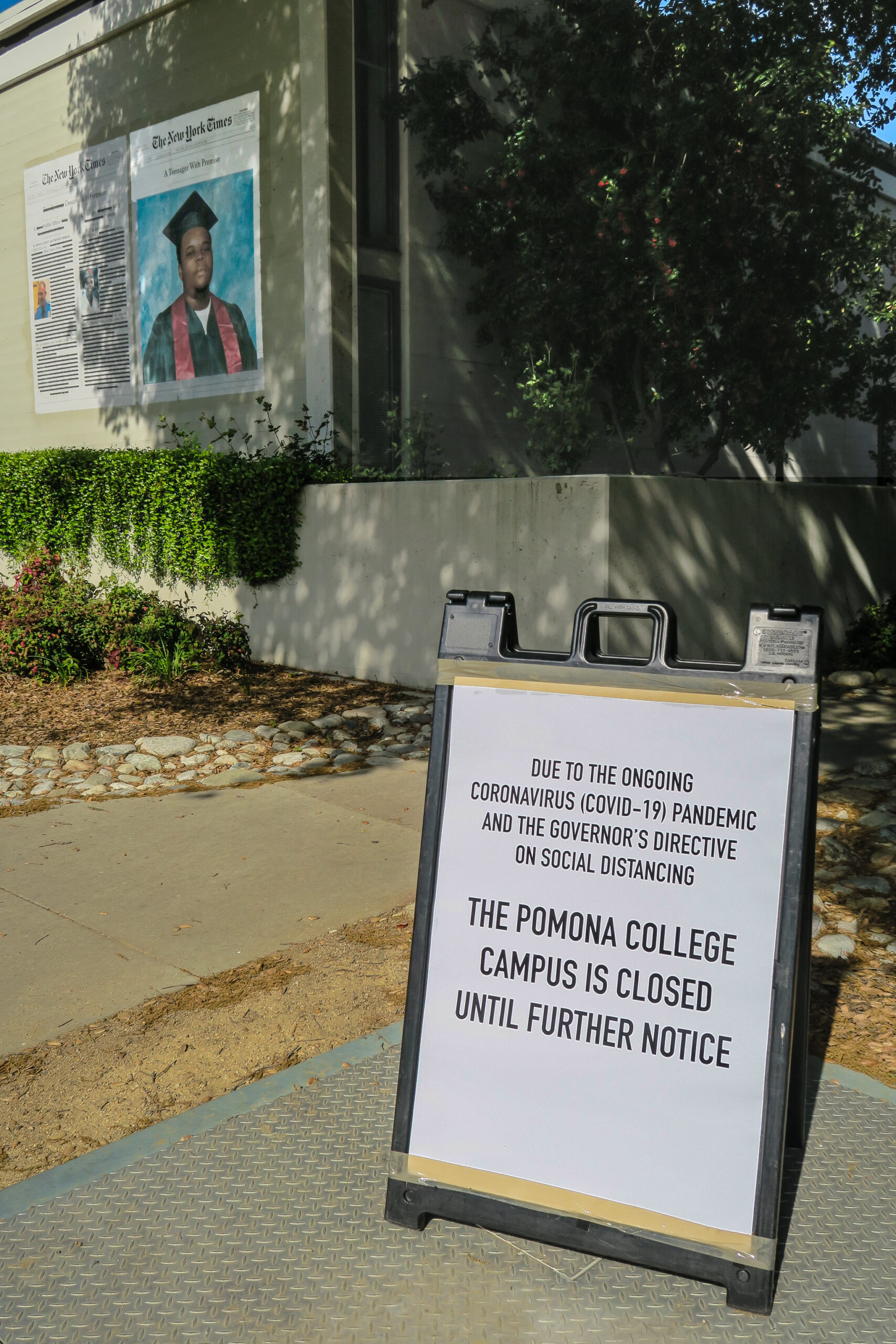

In spring 2020, colleges and universities across the U.S. closed in response to the coronavirus pandemic. As a result, many international students returned to their home countries to stay with their families. [Credit: Russ Allison Loar | CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]

The stress of the pandemic hit Dhar sooner than it did many other international students. In January 2020, Singapore was one of the first countries affected by the novel coronavirus. Initially, Dhar worried about her parents but also was relieved to be in the U.S., which was mostly unaffected at the time. As the virus spread rapidly in the U.S., however, she decided to book a flight home. The decision felt like a defeat in the context of Dhar’s academic path in the U.S. — in the fall semester, Dhar worked hard to overcome her homesickness. “I had finally convinced myself not to miss home,” she says. “But then I was already on a flight home.”

Things only got worse. When Dhar first arrived home, she was determined to take on the challenges of remote learning. But she quickly experienced mental and physical strain as she attempted to synchronize her schedule to daytime hours in Georgetown — a 12-hour time difference. “I thought I was a superwoman,” says Dhar. “I was like, ‘I got classes until 6 a.m.? Let me stay up until 6 a.m.’ It was not a good idea.”

Along with disrupted sleep, the social isolation and uncertainty about her future in the U.S. also weighed heavily on Dhar. By the end of the spring semester, she felt mentally exhausted. “I wasn’t enjoying anything that I did,” she says. “I felt dreary.”

Dreary is an apt description of the feelings of many international students enrolled in U.S. schools during the pandemic. A September survey of 195 students from other countries enrolled in institutions of higher learning in Texas revealed that 71% felt increased stress and anxiety related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Students reported concerns for their health and the health of their loved ones, disrupted sleep patterns, increased social isolation and academic pressure. For similar reasons, the American College Health Association also proclaimed international students as “vulnerable campus populations” during this coronavirus crisis.

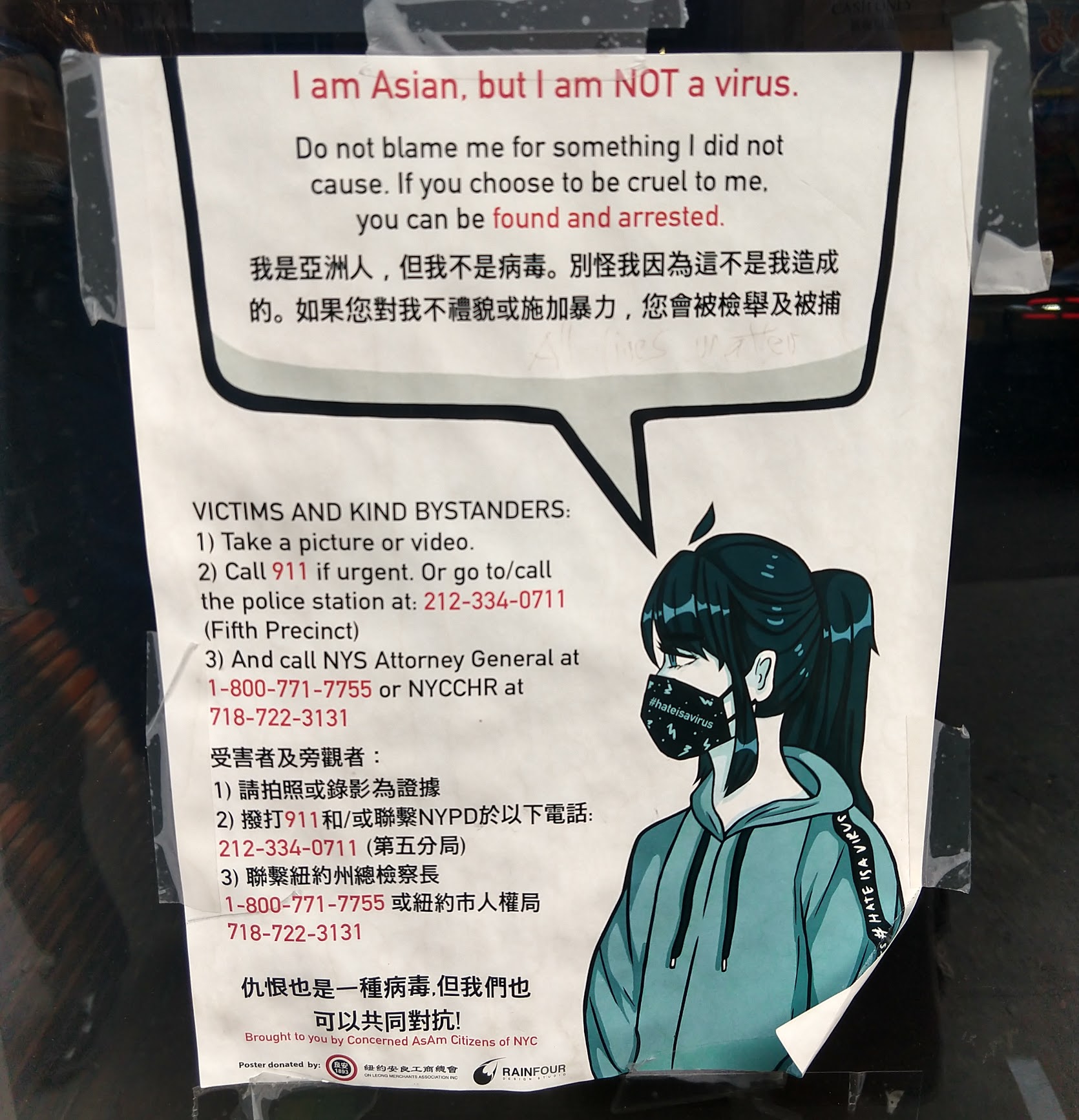

The strain has been particularly acute for students from China, who make up the largest (35%) international student body in the U.S. On top of worrying about their health, many Chinese students endured harassment due to racist rhetoric perpetuated by Trump, among others, who blamed China for the coronavirus.

An anti-racism poster photographed on a storefront window in Manhattan’s Chinatown neighborhood in October 2020. COVID-19 has fueled anti-Asian racism in the U.S., and many international students — particularly those from East Asia — have experienced harassment on or off campus. [Credit: Kches16414 | CC BY-SA 4.0]

There is a new saying among Chinese international students, says Yi Yang, a clinical psychologist based in Massachusetts who specializes in the mental health of international students and families. It goes like this: if the pandemic is a soccer game, China and other Asian countries played the first half of the game, and the rest of the world played the second half. But Chinese people living overseas played the entire game.

International students already faced many mental health challenges prior to the pandemic. A 2009 survey of 130 Chinese international students studying at Yale University found that almost half of the students reported symptoms of depression, triple the rate reported by other researchers of domestic students, according to results published in the Journal of American College Health.

A decade later, not much has changed. A 2019 study that surveyed 490 international students found that nearly half met clinical standards for depression, and one-fourth had moderate to severe anxiety.

Yet international students’ social circles are often small and provide insufficient support in the best of times. “You basically struggle alone,” says Zenith Tandukar, a second-year Ph.D. student from Nepal studying plant sciences at the University of Minnesota.

Tandukar’s mood hit rock-bottom during the pandemic. Last January, coinciding with the coronavirus uptick in Asia, Tandukar’s father fell ill and needed home health support for non-COVID-19 related respiratory diseases. Far away from home and unable to help take care of his father, Tandukar felt guilty and powerless. On top of that, he worried about his parents contracting the coronavirus.

“What ends up happening is one person getting sick in that household and it’s basically like ‘game over’ because there’s nobody to take care of them,” says Tandukar. Fortunately, Tandukar’s parents have not yet caught the coronavirus.

Zenith Tandukar, a second-year Ph.D. student at the University of Minnesota, came to the U.S. from Nepal in 2009 as an undergraduate student. Like many international students, Tandukar has felt constant distress during the pandemic worrying about the outbreaks both in the U.S. and in his home country. [Credit: courtesy of Zenith Tandukar]

But for many international students, their worries during the pandemic extend beyond their own health and that of their family members. In July 2020, while pressuring schools at all levels of education to reopen when hundreds of Americans were dying daily from COVID-19, the White House announced a measure that required international students to take at least one in-person class or else have their student visas revoked. This restriction sent tens of thousands of international students to frantically secure their immigration status. After facing lawsuits from universities including Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, as well as 20 states, the administration eventually relented.

Just two months later, the Trump administration proposed another restriction on international students that aimed to limit their stay in the U.S. to four years — whereas before they could stay for at least the length of their degrees. For many international graduate students like Tandukar, whose graduate programs typically take more than four years to complete, this announcement caused another round of panic and confusion.

“[We] are worried and scared,” Tandukar says. “You don’t have any control over it, but your mind is still racing towards all of the bad things that could happen.” The stream of anti-immigrant measures issued throughout the Trump administration, he adds, has felt like “constant attacks on your mental well-being.”

Though mental health problems affect all students, domestic or foreign, research has shown that international students have been less likely than domestic students to seek and receive mental health support. A 2010 study published in the Journal of American College Health that surveyed more than 550 international graduate students found that only 61% of international graduate students surveyed were aware of the available mental health support services on their campus, compared with 78.6% of domestic graduate students. Only one-third of international graduate students had considered using counseling services, compared with more than half of all domestic students. And while more than a third of domestic students had used these services, only 17% of international students had.

“For international students, opening up to people or mental health professionals is completely different than for American students,” says Tandukar. “At least from my country, we’re very private people. We don’t really like talking about our problems.” Tandukar thinks U.S. institutions and mental health providers should understand that “there need to be more people like us providing [mental health] services — people who we are comfortable talking to.”

To that end, some mental health professionals working with students prior to the pandemic had begun initiatives to make it easier for international students to seek help. “It didn’t matter how good my training was if people didn’t want to come, or they didn’t believe in it. That seems like the major issue,” says Dr. Justin Chen, a cross-cultural psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Drawing on experiences grounded in his Taiwanese-American ancestry, Chen co-founded the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Cross-Cultural Student Emotional Wellness in 2014, a center focused on promoting mental health for non-Western students and scholars. In 2020, Chen’s center created resources in multiple languages to help students from diverse backgrounds cope with issues such as mental health and coronavirus-related racism.

Even still, higher education in the U.S. has a long way to go to offer sufficient and effective mental health support for international students. With many campuses remaining in lockdown or primarily offering classes remotely during the pandemic, international students continue to be isolated from their peers and family, often at huge distances.

In August, Nikita Dhar said she received an email from Georgetown University’s Counseling and Psychiatric Service inviting her to join a support group for international students. However, when she tried to sign up for the group, her request was denied “due to licensure restriction issues.” To Dhar, who studied daily on a Singaporean university’s campus for a month in September to restore a sense of belonging to a campus community, the exclusion pushed her farther away from seeking mental health support to cope with her isolation.

“They shouldn’t flake on us like that,” she says. “It shouldn’t stop at ‘we can’t help you from here.’ It should be, ‘Hey, maybe we can’t help you, but we’ll find a way for you to get help somewhere else because we care.’’’

In line with that theme, Tandukar, the University of Minnesota student from Nepal, emphasizes that campus mental health support shouldn’t just happen within counselors’ offices. Instead, he says, the responsibility should be borne by the larger academic community. “When you’re an international student,” Tandukar says, “you’re really at the mercy of how good the people around you are.”

To effectively care for international students’ mental health, Tandukar thinks, schools should educate and train professors, mentors, staff members and students — everyone in the community who interacts with international students — to be more aware of their foreign peers’ unique challenges, especially during the pandemic, and to find ways to offer comfort and support when needed.

“What needs to happen is that people need to be trained well enough to see the warning signs,” Tandukar says. “They need to be able to go [to the international students] and say, ‘If you’re struggling with something, just let me know.’”

“Then,” he adds, “maybe things will change.”

If you or people around you are experiencing emotional distress or are in a suicidal crisis in the U.S., call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, 1-800-273-8255.