Dyslexia on the digital page

Devices like e-readers and iPads may make reading easier for students with dyslexia

Jillian Rose Lim • November 6, 2013

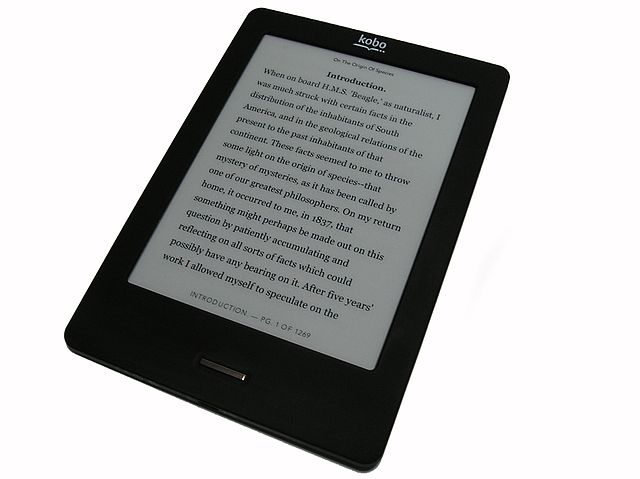

Reading from an e-reader can help some students with dyslexia read faster and with more nuance [Image credit: Wikimedia Commons user Honza chodec]

The e-reader screen looks simple — white text on a black backdrop, four words per line, four lines per page — but it has potential to open up a world of previously inaccessible texts for millions of Americans with dyslexia, according to a recent study from researchers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

Dyslexia — a learning disability that impairs reading fluency — affects about 15 percent of Americans, according to the National Institutes of Health. The new research found that a certain subset of students with dyslexia read better on an iPod Touch screen than a printed page — a discovery that may be related to the technology’s boundless options for personalization.

“Computers have this flexibility that other modes of presentation don’t have,” says astrophysicist Matthew Schneps, the founder of the Harvard-Smithsonian Laboratory for Visual Learning and one of the paper’s authors. “If you print something in a book it could work for a certain number of people, but it will exclude a great many. With computers, you can change a lot of things: the parameters, the spacing. You can customize.”

Schneps and his team tested 103 dyslexic students at a high school in Massachusetts. Each student read a few paragraphs of the Gates-MacGinitie Reading Test from an iPod Touch and then from a standard-sized sheet of paper. The researchers recorded how long the students took with each device and measured their reading comprehension with multiple-choice questions. They found that a particular subset of the dyslexic students—those who had the most serious problems with visual attention —read the text about 30 percent faster and understood it with more nuance when they read it on the iPod compared to on paper. On the multiple-choice test, they did equally well as a control group who never had reading problems. The study was published in September in Plos ONE.

Dyslexia treatment hasn’t changed much since the introduction of the Orton-Gillingham approach in the 1940s, according to Richard Selznick, director of the Cooper Learning Center for dyslexia in New Jersey. The Orton-Gillingham approach posits that a phonological deficit — or a problem with memorizing letters and sounds — causes dyslexia, and educators continue to teach students how to decode phonological letters and sounds rather than addressing visual problems. Selznick calls this approach “old wine in new bottles.”

That’s where Schneps’ e-reader comes in. Schneps bases his research on the visual attention-deficit theory of dyslexia, the idea that the disorder has more to do with how the eye sees the page rather than a comprehension problem.

According to Schneps, students with dyslexia may have a deficit in their visual attention span — meaning that attention lags behind what the eyes see, and the mind lingers on past characters. For example, take the sentence:

“These are the times that try men’s souls.”

A person with dyslexia comprehends the meaning and sentiment of the sentence, but the physical letters could look jumbled, jumping in front of another like a game of leap frog:

“Tehse the are tmes that mne’s tyr suls.”

“Sometimes we get so hung up on teaching kids to decode words, vowels, we forget it’s more important to grab meaning,” says Ben Shifrin, head of the Jemicy School for dyslexia in Maryland. Shifrin believes learning to decode characters is not enough. “The e-reader keeps [students] focused, and they truly get the meaning from the text. That’s what the purpose of reading is. We don’t read to decode, we read to comprehend,” he says.

Jemicy’s curriculum already embraces the use of tablets. “Some research shows children’s brains are wired differently than [previous] eras because of technology. The skills children need today are different. And what I find technology does for the dyslexic student is level the playing field. In my era as a dyslexic, I was told I needed to work five times harder,” Shifrin says.

In addition, if changing the display material can alleviate the symptoms of dyslexia, Schneps’ research suggests that dyslexia may be thought of more as a learning difference than a learning disability, says Shifrin.

“Dyslexics can do everything,” says Ben Shifrin. “They just learn it differently. They need the visual and auditory together.”

Current technology aimed at improving reading ability is still relatively primitive, however. At Barcelona’s Pompeu Fabra University, researcher Luz Rello believes assistive technology should acknowledge individual levels of dyslexia. “One of the disadvantages with today’s technology is that customization, or the ease of the user to change the settings, is very basic,” says Rello, who took an interest in Schneps’ study.

Rello developed DysWebxia, a software model that makes online interfaces more readable by changing text layouts. She integrated DysWebxia into the IDEAL EBook Reader, an application for Android, and Text4All, a website that modifies existing pages whenever you input a URL.

As technology grows as an approach to dyslexia, Matthew Schneps is continuing to examine why the failure to control visual attention may lead to impaired reading. He hopes to use that information to develop advanced technological approaches to treating dyslexia as a visual problem.

It’s a critical goal according to Ben Shifrin because, as he puts it, “technology is the seeing eye-dog for dyslexics.”

3 Comments

I recently downloaded books for my son as he said he finds reading much easier and more enjoyable!

The subjects of this study were from Landmark School, a school for students grades 2 – 12 with language-based learning disabilities, such as dyslexia. The research tool for the study was an iPod, not a Kindle, iPad or other e-reader. 1/3 of the students responded favorably to reading on the iPod because of the small screen which limited the field of view. It’s a very important distinction. Thank you.

It seems unfortunate that people with reading difficulties due to visual issues are grouped together with dyslexics , called dyslexics, and sent to schools where only language-based processing problems are addressed.

I would call that subset of dyslexics visual dyslexics. As my niche is visual dyslexia which can often be diagnosed by simply asking the person if they can describe visual problems that make reading difficult. Many times visual dyslexic

individuals consider that what they see is normal but when asked specific questions about their vision and how they see text will reveal their specific visual problems.

I would say visual attention problems are a fairly small subset of visual issues

that make reading difficult. I believe that the wide spectrum of visual problems described by visual dyslexics have a common cause of being sensitive to visual noise. The concept of visual noise is basically that some visual information entering the eye is redirected to a different location where it overwrites and competes with valid optical data and so becomes noise. The biological mechanism is the absorption and readmission on a different path of photons by autofluorescent proteins in the eye.

I’ve used the fact that visual dyslexics often read more fluently with greatly enlarged text as an indication of visual dyslexia. Dyslexics on the other hand with problems that are not visual have no fluency improvements with increased size text.

Because the various autofluorescent proteins in the eye operate at specific wavelengths of light, it is possible to extinguish the visual noise causal for the visual problems with a multi-wavelength optical filter that filters the wavelengths associated with the different proteins.

The mechanism behind the sensitivity to visual noise in visual dyslexics has not yet been found just as the mechanism behind the sensitivity to auditory noise that is very often associated with dyslexia has also not been found.

Personally I think a lot of the failure of teaching dyslexics in the public school system is due to their noisy environments.Studies where dyslexic students

receive instructions through headphones to eliminate extraneous auditory noise have shown promising results in public schools. It certainly seems within reason that the delayed speech and word confusion shown by preschool dyslexics is partly due by their inability to filter out extraneous noise so that the language they hear is contaminated by a noisy environment in much the same way that many dyslexics have trouble picking out their own name called across a noisy room. But then I’m no expert on dyslexia.

I have had quite a bit of success with removing described visual problems that make reading difficult for visual dyslexics.In fact the filter designed to remove the visual noise associated with the wavelengths of the auto fluorescent proteins in the eye a very high success rate removing described visual problems and make reading difficult.More information about visual dyslexia can be found at dyslexiaglasses.com .