Ever Wondered: What’s the deal with Botox?

Why the toxin in Botox is so dangerous, and why we’re injecting it into our foreheads

Kathryn Free • June 21, 2014

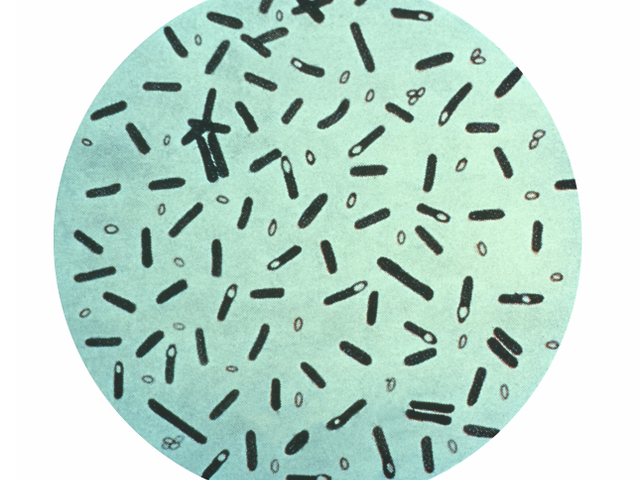

Clostridium botulinum bacteria produce one of the most potent toxins in the world. [Image credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention via Wikimedia Commons]

There’s a natural toxin that’s so deadly a pound of it can kill most of the world’s human population. And yet, millions of people pay big money for its wrinkle-reducing power.

It’s not snake venom, or any manmade chemical like mustard gas. Death by the microgram comes from four varieties of Clostridium bacteria that cause the paralyzing illness called botulism. It’s also available by prescription as Botox. Just this past week, researchers reported how the toxin slips past our gut into our bloodstream, solving a mystery that has puzzled scientists for years.

Happy and healthy Clostridium bacteria don’t cause botulism. However, when these bacteria are stressed, they change how they reproduce. They release spores, armored shells that can withstand freezing and boiling temperatures. The spores thrive in an oxygen-free environment such as a can of asparagus or growler of homemade liquor, and they awaken, multiply and release eight different families of toxins that behave similarly.

When we ingest the toxin, it manages to sneak past the intestinal wall into our bloodstream, even though it’s too large to fit in between cells. In the journal Science, researchers recently reported how toxins manage to bust through. Molecules that carry the toxin attach to proteins responsible for keeping cells stuck together. While the cell proteins are occupied, a kind of passageway between cells opens up, allowing room for toxins to slip through.

Botulinum toxin gravitates toward neurons, or nerve cells, once it enters the blood stream. The toxin enters the neurons and prevents them from releasing acetylcholine, a messenger molecule that tells muscles to contract. Without the message, the muscles start to loosen and sag.

For a person who gets botulism, the symptoms begin in a seemingly benign way. Your eyelids begin to sag. Not so alarming, especially if you haven’t slept well in the past couple of nights. But then the slackness spreads, like a crack in a dam. Your face droops. You have a hard time swallowing. Your shoulders, your arms, your hands are harder to move, and then your thighs and feet. Finally, the dam bursts. The muscles that move your lungs shut down, and you drown in carbon dioxide.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention receives around 145 reports of botulism in the U.S. each year. In the past, botulism killed 50 percent of Americans who had it; however, with improvements in intensive care, that number has dropped to under five percent. An antitoxin prevents the toxin from circulating in the blood, though it can takes weeks or months to fully recover.

Ironically, the toxin’s relaxing property makes it valuable for medicinal and cosmetic purposes as it smooths skin and calms overactive muscles. Going beyond wrinkles, doctors prescribe Botox for conditions such as incontinence, excessive blinking and migraines. Last year, physicians performed 6.3 million Botox procedures in the U.S. alone. In these cases, the dose is a thousand times lower than what it takes to kill; however, there is a slight chance of the toxin’s effects going beyond the injection site.

In minuscule quantities, it’s youth in a syringe. A little more than that, and it’s lights out.