Are bilinguals really smarter?

Despite what you may have read, it’s not so cut-and-dry

Alexandra Ossola • July 29, 2014

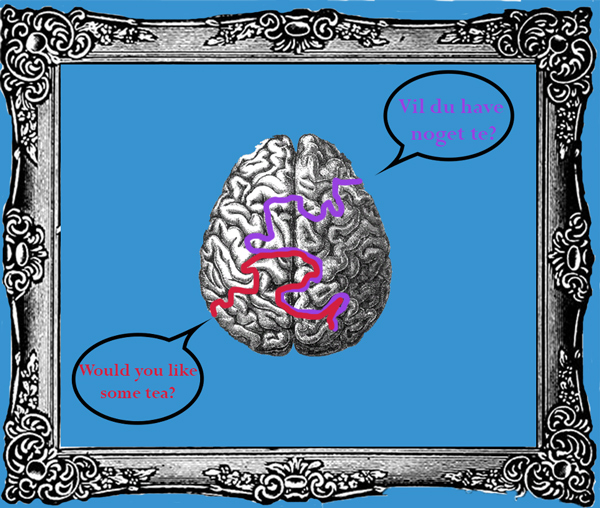

How does your brain figure out how to process two different languages? And why doesn't it mix them up? Its powers of executive function are at play. Illustration by Alexandra Ossola

Even as a young kid, I always wanted to be bilingual. I surrounded myself with friends from all over the world, and, after years of often-tedious training and practice, became relatively fluent in Spanish. But, starting a few years ago, pieces began appearing in major news outlets, The New York Times and NPR among them, all toeing the same line: bilinguals are smarter, says science. I was curious: what does “smarter” mean? And even though I learned Spanish as a young adult, does this later adaptation still grant me membership to the smart group?

This idea that bilinguals are smarter is relatively new. Up until the 1970s, most educators believed that learning two languages at once would confuse children and slow their cognitive growth. But science disagreed with these convictions, says Ellen Bialystok, a professor of psychology at York University in Toronto, Canada. The advent of neuroimaging technology (specifically the CAT scan) in the 1970s granted scientists a new way to investigate how different brains process language. But the emerging evidence wasn’t the only reason bilinguals seemed smarter; Americans’ changing attitudes played a big part, Bialystok says. As the cultural xenophobia of the 1950s subsided, society as a whole began to accept the shift towards multiculturalism.

Bialystok has been researching the bilingual brain for decades, and she is adamant: Bilinguals aren’t smarter than their single-language counterparts. “I think it’s a real problem that [my work] may be interpreted that way,” she says. Bilingual brains differ in their use of executive function — a system that helps the brain access particular regions or memories when prompted, like a neurological Dewey Decimal System. A person needs executive function to switch between tasks or look for a friend in a crowded restaurant. When less developed, executive function also makes adolescents more reckless.

Contrary to media reports, executive function is not the same as intelligence, Bialystok reiterates. But pinning down the concept of intelligence itself is not an easy task. Dictionaries define intelligence as the ability for a person to absorb and apply information — and that’s part of what executive function does, too. But this abstract definition of intelligence doesn’t mean much to science, Bialystok says, and “that’s one of the reasons you can’t say that bilingualism (or increased executive function) gives you more of it.” Intelligence and executive function have a murky relationship and, because of this obscurity, Bialystok may be right to doubt their synonymy.

But it’s undeniable that the bilingual brain has a particular prowess. “We might expect that bilingual speech would be riddled with errors, that sometimes you slip and the wrong language comes in,” Bialystok says. “But that doesn’t happen.” So, why doesn’t it?

The bilingual brain does something kind of surprising. For each language you learn, you develop what is called a lexicon—a series of rules, procedures and structures that tells your brain how to understand words. But you don’t usually hear words in isolation, says Albert Costa, a neuropsychologist at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, Spain. Words are tethered to context, and your brain uses the lexicons to anticipate what could come next. If you’re truly bilingual, you have this predictive power for both languages. But the surprising part is that the parts of your brain where the lexicon is stored don’t just turn on and off when you need them; they’re engaged all the time.

“The monolingual will look at that animal and say, ‘dog’,” Bialystok says. “But to a bilingual, two alternatives present themselves. That means that bilinguals are always having to make a decision that monolinguals just don’t have to make.” These micro-decisions strengthen the executive function; the more your brain has to make the same kinds of choices, the better connected that wiring becomes, clearing the path for future communications from executive function. Changing neural pathways to meet new needs is a concept called neuroplasticity, and these constant tiny decisions reinforce the brain’s new configuration to make them more efficiently.

These changes in brain wiring sound good in theory, but how do scientists know for sure? Bilingualism creates changes in brain wiring that researchers can actually see. Many researchers use fMRI machines to track brain activity, creating an image of the brain by tracing oxygenated blood as it flows through it. Arturo Hernandez, a professor of developmental psychology at the University of Houston, used fMRI imaging to take brain scans of both bilinguals and monolinguals as they identified objects. He determined that bilinguals had more activity in both hemispheres of the pre-frontal cortex, which controls executive function. The increased activity, he hypothesized, stems from the need to repress one language in order to answer correctly in the other. Other researchers, including Bialystok and Costa, have conducted similar experiments over the past ten years, all with comparable results.

Even if the relationship between bilingualism and actual intelligence is unclear, executive function can help people do a lot of things that may make them seem smarter, such as doing more things at once and cancelling out distractions. Many people believe that knowing at least one other language makes it easier to learn a new one, and cognitive function may play a part in that—the equivalent of good study habits for your brain. But Bialystok thinks cognitive function has less impact on language than do the sheer similarities between languages’ structure and vocabulary. “In learning those patterns, you can get a bit of a free ride in learning a new language,” she says.

Despite the overall cognitive benefits, bilingualism may present some linguistic disadvantages. When children learn vocabulary, Costa says, monolinguals spend more time retaining words in their one language, while bilinguals have to construct two different vocabularies. Many factors can influence vocabulary acquisition, such as a person’s home environment and how much she reads. But, Costa says, “Everything else equal, bilinguals may have a reduced vocabulary in each language.” Bilinguals certainly know more words overall, he notes, but in each individual language, their vocabulary may suffer. However many bilinguals fill in the gap later in life, he suggests, using vocabularies just as vibrant as those of monolinguals. The long-term cognitive benefits, Costa says, really outweigh the minimal short-term detriments.

So maybe my natively bilingual friends aren’t necessarily more intelligent than I am. But can later learners like me still acquire better executive function? Costa has good news on this front. “What’s important is how you use the language, and how often you use it,” he says. “Everyday practice with the second language makes you control the language; you need to focus on the new language while you [ignore] the other one. This is what seems to help the development of executive function.” Frequent practice, it seems, does more than increase a person’s knowledge of the new syntax and vocabulary—the brain’s powers of executive function get stronger and more adept at making those tiny decisions for which language to use.

To me, the biggest advantage in being bilingual is the same as having great international friends: It allows a person to understand a different way of thinking, with unique philosophies and assumptions built into how others see the world. It would be nice to be able to thank my friends’ parents for dinner in flawless Arabic and to reap the benefits in my cognitive function for doing so. And even though I may never sound like a native speaker, I am content knowing that I could gain the same cognitive benefits of bilingualism over time. All I have to do is keep practicing.

5 Comments

Most bilinguals learned both languages when they were young. The subconscious mind is wide open until we reach six or seven years old and therefore we are prone to be sponges at a young age. I do not believe that bilingual people are any smarter than the average joe. They just take advantage of the access to the subconscious mind’s hyper-ability to learn.

Yes…they are intelligent and smart. But not smarter. Some people are smart with numbers but not languages…other are smart for sports….maybe a bilingual will not be smart with numbers but faster to learn a new Language.

If multilinguals were smarter, it would be difficult to say, but with English being my first language and knowing study methods, I forge the opportunity to learn new English at 29 every single day. I almost feel better, but not smarter.

Bialystok also found out that Alzheimers develops laer in bilinguals. That has to be worth something.

This discussion and references are interesting, but the arguments appear speculative. It considers activities that have been observed in the brain, but it does not relate to proven output issues like working memory. It is unclear what is precisely meant by bilingualism. The references does not consider the balance of the levels of fluency achieved in each languages and when they are learnt.

There is strong evidence that the hard wiring of languages is developed from birth and the wiring of later language learning is different.

There is distinction between crystal intelligence, which is possession of knowledge, and fluid intelligence, which is reasoning. There is no evidence that being smarter relates to intelligence. Eysneck refers to research that illustrates that those with high working memory have more attentive control.

The research referred to may simply identify the neural processing of bilingualism. It would be extremely difficult to make comparative studies to establish any added value of bilinguals have in terms of learning outcomes, because bilinguals cannot have their development of bilingualism turned off.