Why eating local isn’t always best for the environment

It’s what you eat, not where it comes from, that matters most, new analyses suggest

Jonathan Moens • May 8, 2020

![Transportation accounts for around 6% of carbon emissions in the global food system, new analyses suggest. [Credit: CC0 | Pixabay]](https://scienceline.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/eating-local.jpeg)

Transportation accounts for around 6% of carbon emissions in the global food system, new analyses suggest. [Credit: CC0 | Pixabay]

Dissatisfied with the United States’ wasteful and planet-degrading food system, San Franciscan food activists Jessica Prentice and Sage Van Wing came up with an idea in 2005. They challenged everyone they knew to eat nothing but locally grown food for a month.

It wasn’t an easy challenge, says Prentice, but by 2007 their idea had gained so much traction that it required its own word. “It was that challenge that birthed the word ‘locavore,’” recalls Prentice, a chef and author. That same year, ‘locavore” became the New Oxford American Dictionary’s “word of the year.”

Ever since, “eat local” has become a widely-accepted mantra for people seeking to reduce their carbon footprint. It’s even recommended by large institutional bodies, including the United Nations.

It may also be the wrong message. A recent set of analyses led by Hannah Ritchie, a data scientist from Oxford University, concludes that eating local can be misguided advice. “Many have the misconception that eating locally-produced food is one of the most effective ways to cut their carbon footprint,” writes Ritchie in an email. “But most of us underestimate the emissions involved in the production stage of food.”

With food production accounting for about a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions, knowing which products and food systems are most environmentally friendly is key, explains Ritchie.

Her analyses are based on the most comprehensive meta-analysis of global food production to date, collecting data from 38,700 commercially viable farms in 119 countries. Her central finding is that, on average, transportation of food accounts for less than 10% of carbon emissions in the global food supply. It’s dwarfed by emissions related to changes in land use, such as deforestation, as well as farm-related emissions, notably the release of methane from cow farts and burps.

Most emissions come from land use change and farming practice. Source: Our World in Data

The misconception, explains Ritchie, is rooted in a public misunderstanding about global food transportation. Many assume that food grown in foreign countries is imported via airplane, but actually only 0.16% of global food transportation happens by air. Most of it, 60%, happens by sea, which releases about 50 times less greenhouse gas emissions than air transport.

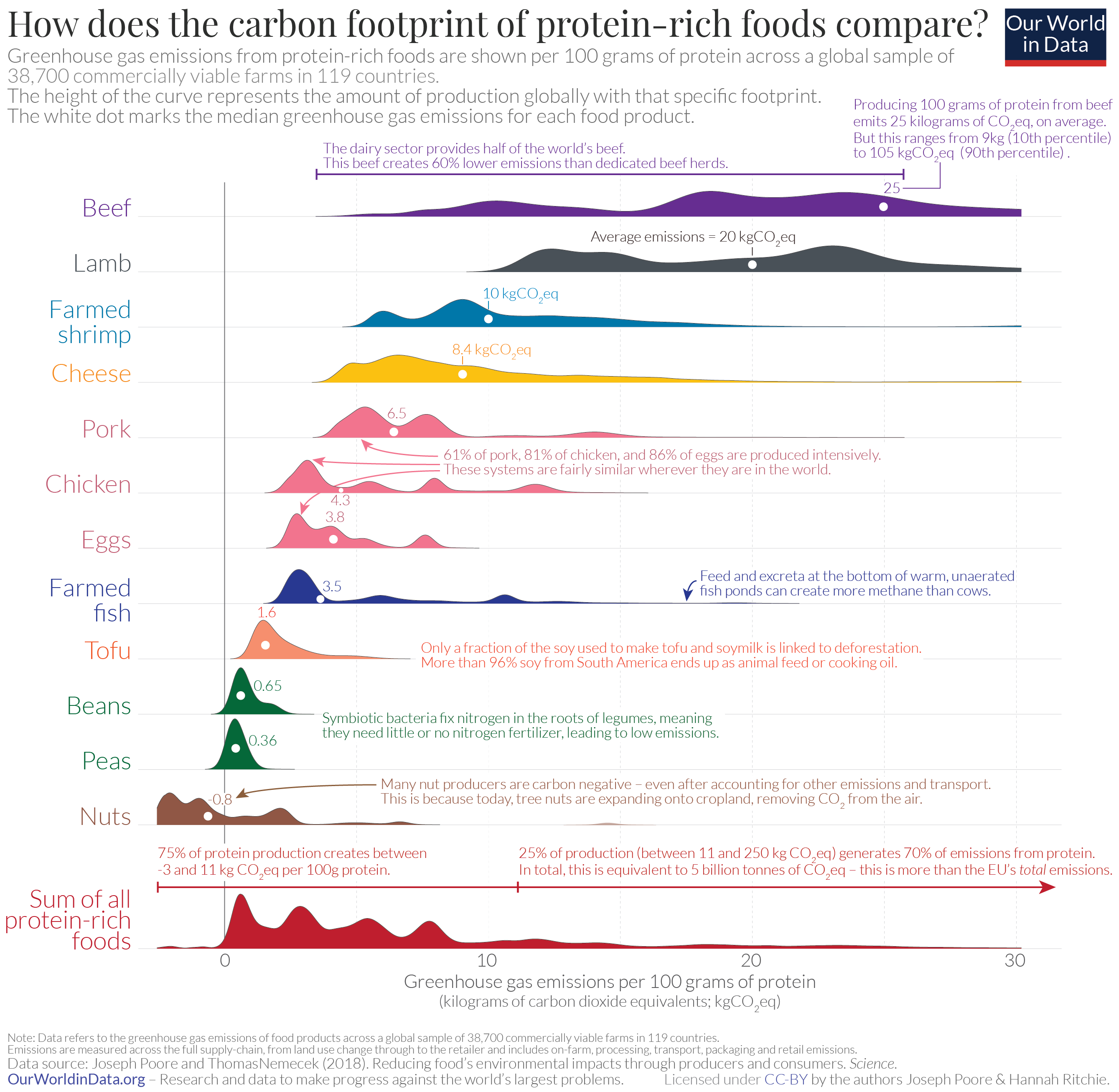

It’s what you eat, not where it comes from, that really has an impact, Ritchie says. In her analyses she illustrates greenhouse gas emissions broken down by 29 food types — ranging from meat and dairy to nuts and vegetables. Consistent with previous findings, red meats — particularly beef — emitted the most greenhouse gases, whereas plant-based foods emitted the least. “We need to eat a lot less meat, and the meat we do eat needs to be the lowest-footprint it can be,” Ritchie concludes.

In a follow-up analysis, Ritchie shows that these results hold true even when accounting for stark differences in how these foods are produced. For example, the most sustainably produced beef still emitted more greenhouse gases than the least sustainably produced tofu.

Her message is getting support from other experts. “The blanket advice to eat local is misguided,” says Henning Steinfeld, an agricultural economist at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations who was not involved in the Oxford analyses. “It needs to be qualified.” As a real-world example, Steinfeld explains how countries such as Saudi Arabia, which rely on importing fruits due to land and water shortages, would almost certainly incur a higher environmental footprint if they were to switch to producing these domestically.

But while experts criticize eating local as being largely ineffective in reducing one’s carbon footprint, the locavore movement is still going strong, says Prentice, its co-founder. Restaurants, supermarkets, and food markets all still emphasize the fact that they use local produce, she adds. A 2018 Gallup poll confirms this, showing that nearly 75% of Americans say they actively try to include locally produced food into their diets.

A major step that could help consumers eat more sustainably, says Ritchie, would be to encourage producers to put labels on air-freighted foods. She adds that placing clear, colour-coded labels on food to illustrate their carbon footprint could help consumers make more sustainable food choices. A team at Oxford University is currently developing the food analytics to help achieve this goal in the near future.

Animal products emit significantly more carbon emissions than plant-based foods, regardless of how they are produced. Source: Our World in Data.

Prentice, however, says she’s unimpressed by these findings. She says that by focusing only on climate-warming emissions, Ritchie and others are failing to account for other benefits of eating local — especially supporting small-scale farms that create a sense of community.

“Nobody who’s eating local beef is eating factory farm beef,” Prentice says, adding that “factory farm beef is coming from few, disgusting farms in the United States that are mega farms.”

Still, Prentice acknowledges that obsessing over how many miles food has traveled — a unit known as “food miles” — without considering the farming practices employed to produce them is a mistake, even for the most dedicated locavore. “Food miles is a piece of the picture but, to me, it’s far from the most important part of what the local eating movement is about.”

People eat locally for different reasons, says Brent Sohngen, an environmental economist at Ohio State University who was not involved in the analyses. While eating local does not guarantee a low carbon footprint, locavores can help strengthen communities and support local industries, he says. But if the sole purpose of the movement is to help the planet, eating local is misleading advice, he adds.

With demand for meat growing, especially in the developing world, it’s especially important for the public to understand that what you eat is more important than where it’s grown, says Ritchie. “We’re at a crucial point in shifting attitudes towards diets and environmental impact.” With plant-based and lower carbon-intensive diets becoming increasingly common in the Western world, Ritchie is “cautiously optimistic” that the message is starting to get out. “The signs are positive that people are interested in understanding how they can have a positive difference.”

4 Comments

Great analysis

I read today in the Gaurdian’s re-hash of your article’s analysis. Not really a surprise that supply chain and logistics costs/protocols would increase locally. You can’t apply just-in-time practices to just-in-the-boonies farms, scattered all over the place. But you cannot discount the value of the product being superior, or more nutrient dense (well i’m sure someone will). A bit of a conundrum: planet vs health. I don’t see the small farms winning this in the long run, cost increase and government intervention. ADM, Cargill, General Mills, etc… they win the day and the future. SWAT shows up at raw milk farms, that friendly reminder will have you stop questioning homogenization and sipping on UHT lactose free White Russian’s by happy hour.

I’m sorry but let’s follow the Yellow Brick Road …aka the money. I seen this kabuki dance before. “ distinguished “

Journalists put out an article or white paper type publication and then upon following their employers and or funders..,names like Monsanto , General Mills Tyson etc …One article doesn’t shift the balance btw.

Superb Article